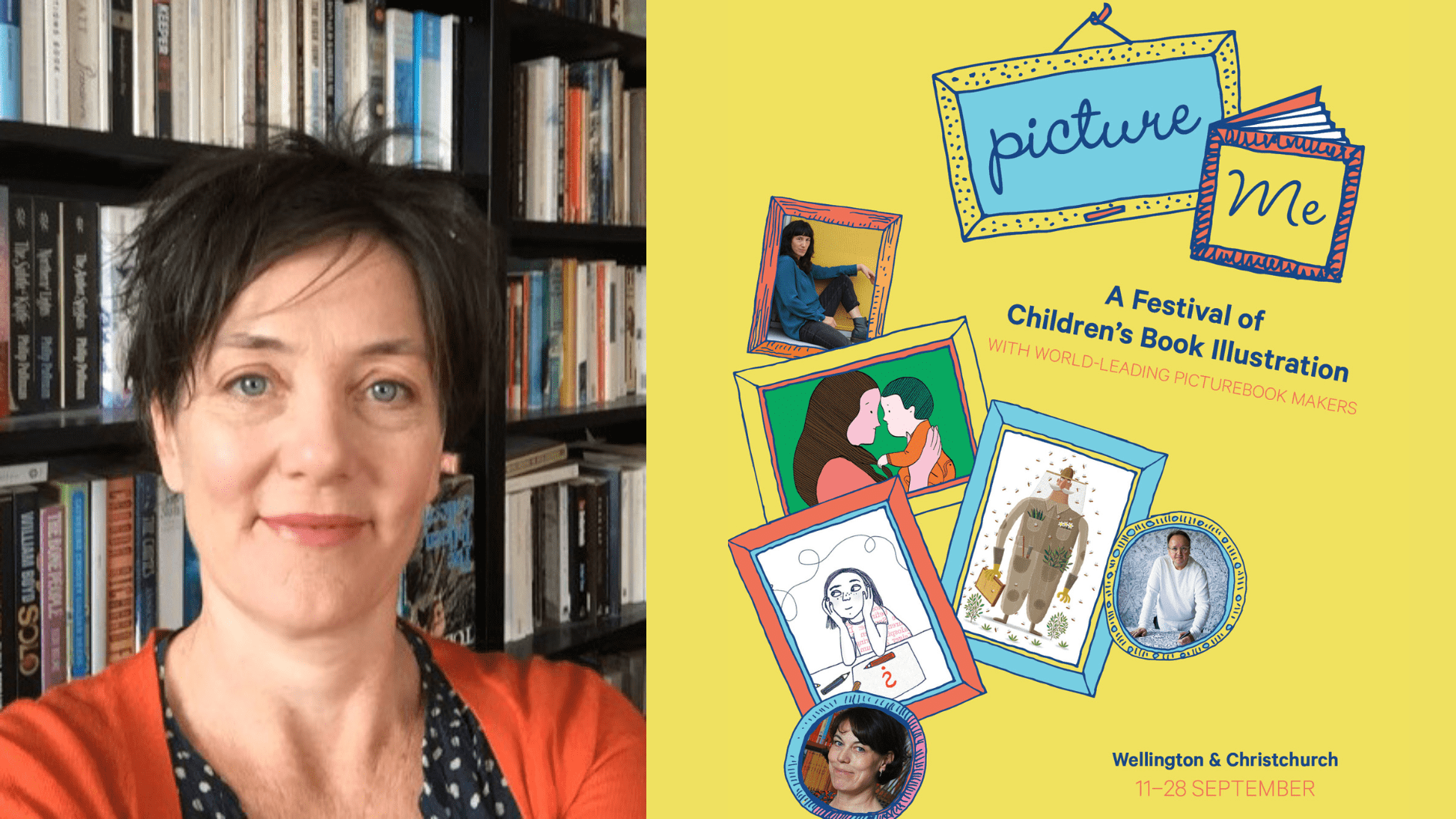

Picture Me promises a vibrant cross-cultural celebration of illustration and identity for children and professional illustrators alike. The Sapling sat down with Gecko Press publisher, Rachel Lawson, to find out what the festival is all about.

The Sapling (TS): During the month of September, Picture Me festival is welcoming three award-winning illustrators from France, Germany and Poland to New Zealand for the Picture Me festival. How did the idea for the festival come about?

Rachel Lawson (RL): Julia Marshall (Gecko Press Founder) and I have talked about children’s book festivals a lot over the years at Gecko Press! We have always felt there is a space in New Zealand for a festival with events for children that also caters to the adult and professional interest in writing and illustration for children.

I was particularly inspired by going to the Montreuil Children’s Book Fair in Paris a few years ago—it’s an annual children’s book fair that mixes trade business and book stalls with talks and events and author signings. It was such a buzzy event. These fairs are important professional events but also have children crowding the halls to meet authors and have their books signed.

European authors Leo Timmers and Aleksandra and Daniel Mizielinski came to Wellington Writers Week in the 2014 Aotearoa New Zealand Festival of the Arts. I was mesmerised by Leo’s session. I hadn’t seen anyone talk about children’s books to an adult audience in this ‘festival’ way—about craft and philosophy and creativity. It is true of most people in the European children’s book scene—they have a wonderful culture of taking children’s books seriously.

Then in 2019, Gecko Press brought two French illustrators, Clotilde Perrin and Éric Veillé, to New Zealand. That was super fun. They loved coming; they did events from Auckland to Dunedin and all sorts in between. They combined this childlike joyfulness with deep thinking, which goes straight to what I love. So, five years later we are doing it again with Picture Me in collaboration with Goethe-Institut, the French Embassy and the Embassy of the Republic of Poland.

TS: Guest speakers Aurore Petit and Antje Damm are both published by Gecko Press, and Piotr Socha is one of Poland’s most popular cartoonists. How did you first meet these illustrators? And what is it about their work that resonates with you?

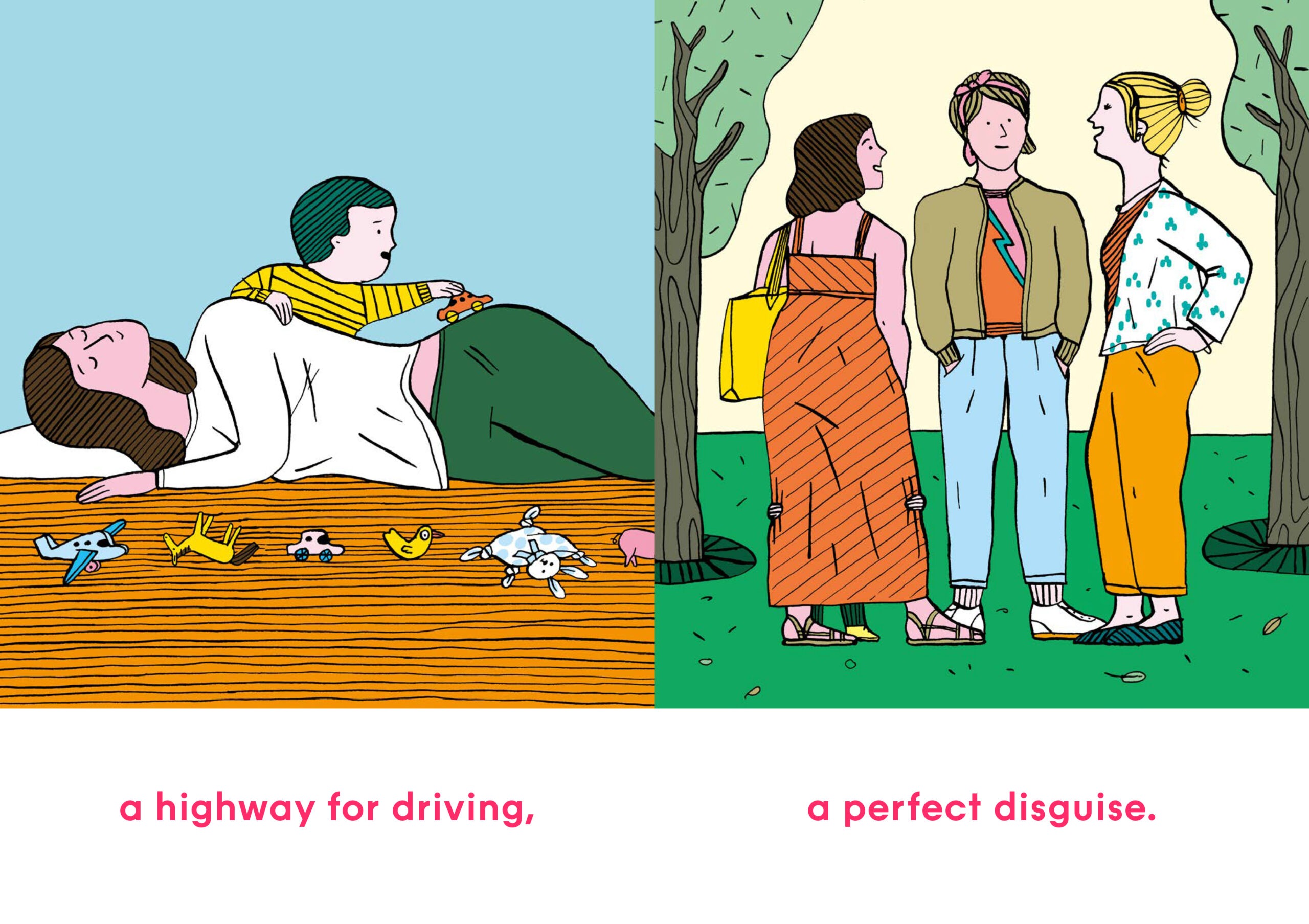

RL: I was first shown Aurore Petit’s book Une Maman C’est comme une Maison at the Montreuil Children’s Book Fair, where I met her publisher Valérie Cussaguet . It’s such an original book—vivid, graphic art and a really conceptual idea combined with a warmth and directness that connects with children. In the book, a mother is described as the baby sees her through a series of metaphors. It sounds intellectual, but it’s really warm.

We’ve been publishing Antje Damm for longer, now with three books (although she’s published ten times that many in German). Antje has the most extraordinary range in her work for different ages and working in different media. She’s very talented, and again I love the warmth of her books. She tells simple stories that are funny and very human.

Our partnership for this project included the Polish Embassy. We don’t currently have a Polish author on our list, so I asked our friends at Dwie Siostry, a fantastic Polish publisher, and they recommended Piotr Socha, an author of a number of big non-fiction books. He was immediately so enthusiastic about coming we knew we had our man!

TS: The central theme of the festival is how children’s books help shape our identity. What role do illustrations play in shaping identity through picture books?

RL: Books are one of the many ways the world tells us who we are and how we are valued—in turn shaping our view of what we can be. I learned this through the lens of feminism and language when I was growing up. These days we understand much more about culture, gender, all sorts. The choices an illustrator makes have a huge impact on how the book is read and who responds to it—the illustrations can be a very direct representation of characters in the story.

We have shaped our festival around the idea of a picture book as both window and mirror. In a picture book mirror, we see ourselves, where we fit and who we sit with. Through a picture book window, we see the world—it can look the same as our own or very different, but we almost always find that the people (or bears, triangles, pigeons, crayons) have hearts the same as ours.

TS: A key part of the festival will be workshops in schools for children and free events for whānau. In your experience, how do you know when a child has really connected with a book?

RL: Usually by wanting to read it over and over! Returning to familiar books is such a part of our childhoods. Re-reading and re-looking feel intrinsic to what reading is for at that age. As a children’s book publisher, we are always looking for the book that will survive dozens of readings, can be passed down, and whose words or images can enter the family lexicon. It is almost strange the way book reading becomes a one-time-only thing in adulthood.

I love that look of concentration, almost seriousness, on children’s faces as they look at picture books. You can see the whirring brain cogs. As adults it’s easy to be busy with the words and the story, but children are so good at properly seeing the illustrations.

As adults it’s easy to be busy with the words and the story, but children are so good at properly seeing the illustrations.

TS: The festival includes industry workshops for illustrators, which will stimulate an intriguing exchange of ideas across cultures. Are there any international trends in illustration you’d like to see taken up in local picture books? Or equally, are there any trends we should steer clear of?

RL: Certainly there is a long history of being unafraid in European children’s books—of covering topics or including illustrations that don’t feel toned down to protect the reader. We come up against that from time to time at Gecko Press generally about things that don’t trouble the child reader at all. They are often worries that exist only in the head of the intermediaries between the book and the child.

I think ‘sweet’ can be an easy default for children’s illustration, but illustrations don’t have to be sweet to appeal to children. Again many European countries are more open to this—like the ‘beautiful ugly’ idea you see in a lot of Swedish picture books.

TS: Gecko Press is highly-regarded for publishing children’s books from around the world. What’s been your biggest takeaway from attending international book fairs?

RL: There are so many publishers creating so many great books! Book fairs are both overwhelming and brilliantly stimulating. I try to stay focused on what makes a ‘Gecko Press book’ to keep it manageable—the quality of the writing, the centrality of the child’s point of view, warmth, the idea of ‘curiously good’, and is this different from something we have seen before? The children’s book community is incredibly nice to be part of. People are very friendly and open, it’s a very warm profession.

TS: You’ve recently stepped into your role as Publisher at Gecko Press. What are your aspirations for the next era of Gecko Press?

RL: Although it’s a new role, I have been doing the job alongside Julia for many years, so my immediate aspiration is to continue what we have built. I have a very clear vision of what makes a Gecko Press book and hope to continue choosing and publishing within that.

My aspirations are about the scale of what we can now do. Being an imprint of Lerner Publishing Group, our new base in the US will open the American market in different ways and provide some new opportunities—Lerner is strong in the school and library market, for example, and we’ve already created a Spanish translation of one of Gavin Bishop’s books for sale in the US. It will be interesting to see how we can use the resources of a much bigger company than we have been.

TS: Next year will mark twenty years of Gecko Press. What has been the biggest change in children’s books over that time? And are there any changes you wish to see in the sector?

RL: One of the themes of our festival is identity, and there is no question that children’s books are much better now at reflecting different identities, representing many ways to be and feel, telling stories from all sorts of people and from all around the world. The growth of translated books feels connected to that—adding to the diversity of voices and perspectives.

Funnily alongside this has been a focus on ‘local’ in all the different markets we publish into, which has made some things harder for us as a publisher of global books and books in translation—the drive in schools and libraries for books that tell our own stories is pretty fantastic, but I think there is still a need to look out into the world. That would be the thing I’d like to see—that we keep looking outward. British writer Frank Cotterell Boyce (the current UK children’s laureate) has talked about the European books he read growing up in the 1960s—a really rich period for children’s books in translation. He says of reading those books: “You felt like the world belonged to you.” I love the idea that books in translation can make children feel they belong in the world and the world belongs to them.

Picture Me festival will run events for adults and children from 11–19 September 2024 in Wellington and 27–28 September 2024 in Christchurch. Visit the Gecko Press website for details on discussion panels, networking events and an illustration exhibition. Picture Me is brought to Aotearoa by Gecko Press, the Goethe-Institut, the French Embassy and the Embassy of the Republic of Poland, funded by the Franco German Fund, with additional funding support from Creative New Zealand and the Polish Book Institute.