Alistair Hughes searches for the formula for good science communication for kids.

Ernest, Lord Rutherford is famously credited with proclaiming: ‘If you can’t explain your physics to a barmaid, it is probably not very good physics.’ These days hospitality workers probably have a perfectly robust grasp of science and many other topics besides, so perhaps a worthier challenge lies with children’s book authors in presenting science to young readers.

Children’s encyclopaedias were once a source of knowledge for growing minds, but in the age of electronic information titles like Look and Learn, Tell Me Why and Maurice Burton’s World of Nature seem to have long passed into obscurity. So how can we effectively share science with modern young readers?

A common mistake is to believe that the required simplification of information will mean that the task will also be simplified. In fact, distillation of knowledge is probably a better description. And as any scientist or whisky distillery will tell you, this is not a process to be underestimated.

Janet Raloff, editor of US-based magazine for middle students, Science News Explores, has a word of caution; ‘Science journalists often think writing for kids will be easier than for their usual audience, [but] it’s not easier at all. It’s just different.’

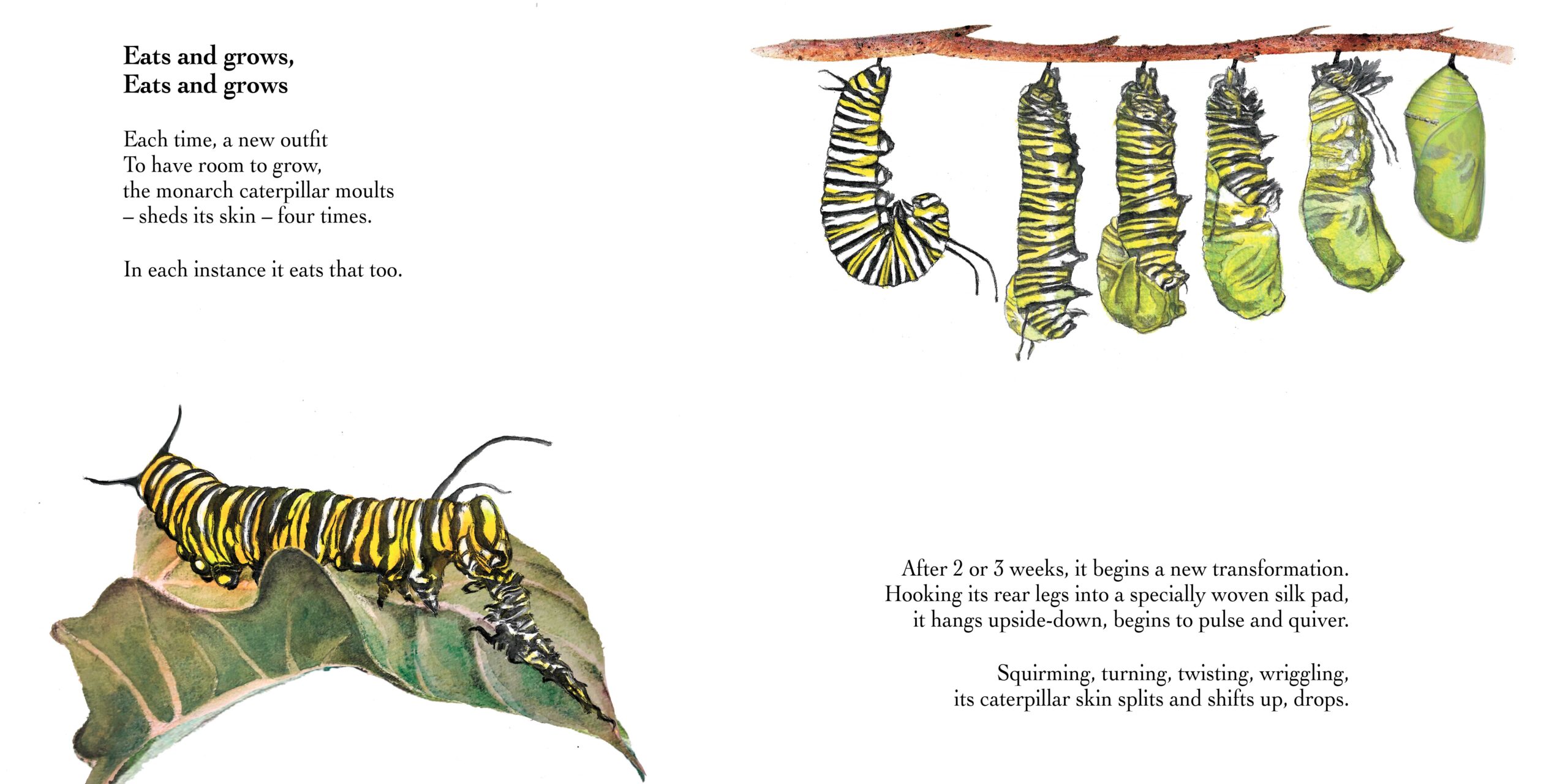

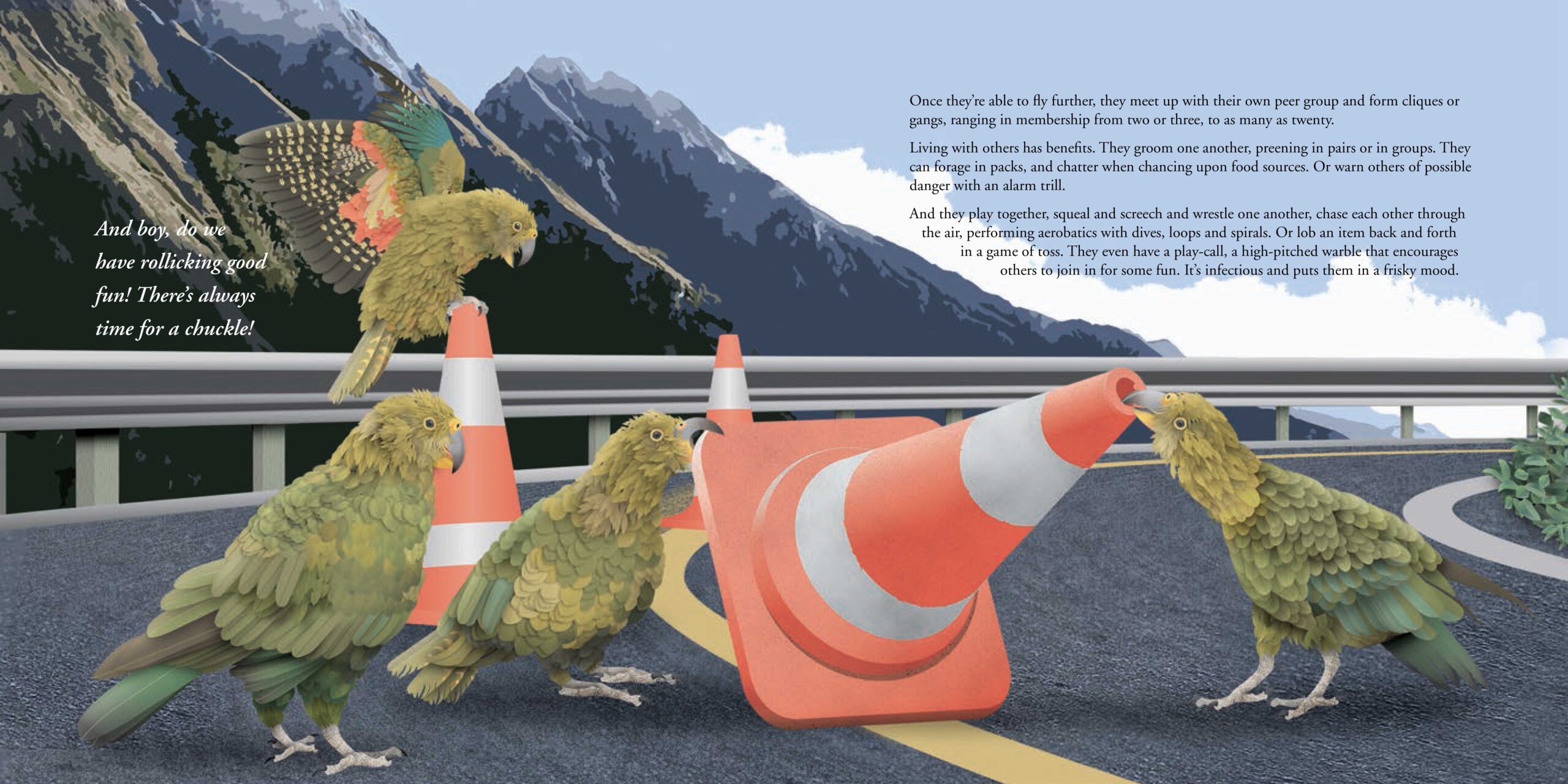

‘When you’re thinking about writing science for kids, you want them to be excited and intrigued’, says New Zealand author Annemarie Florian. ‘But you also have to be excited about the subject yourself. I’m of an age where we really didn’t get a very good science education at all. So it’s also about being honest, because I don’t know any more than anybody else. But I want to be informed and I’m happy to communicate my sense of wonder.’ Annemarie has focused on natural history, with popular books about kiwi, the giant wētā, kārearea (the native falcon), kea, snapper and the monarch butterfly. She credits botanist Robin Wall Kimmerer’s book Gathering Moss with opening her eyes to the natural world around her. ‘And that’s what good research can do. So I read a lot of research papers to find what’s current on a topic. I’m not a scientist, I think that my skill lies in being able to distil information down and find those absolutely critical descriptors.’ As important as facts are, Annemarie feels conveying them effectively to a young readership is paramount. ‘You want those facts to be so well communicated that it’s like a direct line to the mind.’

When you’re thinking about writing science for kids, you want them to be excited and intrigued.

Margaret Mahy Award winner Maria Gill has written over 62 nonfiction books for young people. She opens up the world of science to her readers by focusing on New Zealanders famous in their field such as Lord Rutherford and cosmologist Beatrice Hill Tinsley, with space pioneer William Pickering’s story to follow next year. ‘I like to have an underlying message that will inspire kids to achieve goals that they want to reach. With Ernest Rutherford’s story, it was about not giving up. He failed three times to win the scholarship that he needed, before he finally succeeded.’ With her teaching background, Maria keeps an eye on the school curriculum, and noted an emphasis on science and history. ‘I believe you’ve got to have a book which chimes with the education system somehow’, she says. After settling on a subject, Maria focuses on key questions that she wants to cover, to avoid researching too widely. ‘I’ll do some reading, such as a biography written for adults, then I write a plan, working out exactly what I want on each page.’ More research follows before she begins her first draft, fact checking herself constantly. ‘I do try to cover all the key events of someone’s life, but when I’m reading a first draft, I often realise some details included aren’t crucial to the tale for children.’ Maria finds that including a glossary at the back of the book is a good way to include extra information, which her readers can refer to without interrupting the flow of the story.

The next stage can be both rewarding and challenging for an author: seeking an expert for consultation and checking. For Annemarie this has usually been a positive experience. ‘Generally, people are really generous with their information,’ she says. ‘I never approach specialists until I am at the end of my research, because otherwise it’s too much to ask someone to take on at the beginning.’ Annemarie credits her background as a librarian with her fondness for research. ‘Inevitably, I read an awful lot, but I think that’s probably often the wrong path for an author to take. Nonetheless, it is the way I go, and it allows me to actually look at the world, to concentrate and give myself over to the learning and the listening.’

Maria consulted a professor of physics for her Rutherford book, and surviving family members for her account of Beatrice Tinsley’s life. ‘They were extremely helpful. However, I’ve also had experts who wanted to rewrite my draft using long, convoluted language while I’m trying to simplify it. I’ve agreed to amendments, but if it keeps happening I’ve had to ask them to please not rewrite what I’ve written, just tell me if it’s factually correct.’ She has learned to take a firmer stance, and has even had to explain that it will be edited by a professional afterwards. ‘It can be a little embarrassing when someone thinks that they can do it better. They have valuable knowledge, but don’t write in a language that children can understand.’

In many ways this is the crux of the issue; conveying scientific information that has been simmered down so the result still contains the essential ingredients, but is now imbued with a more enticing flavour. As science journalist Matt Shipman laments: ‘If you’d really like to challenge yourself as a writer, I suggest writing about science for kids. Specifically, try to explain a basic science concept to children under the age of eight.’ There does not appear to be a magic formula, and the approach may differ for every author.

Annemarie emphasises wonderment, and quotes Terry Pratchett, who once described humanity as ‘a species that lives a few miles above molten rock and a few miles below a vacuum that would suffocate us … and there’s nowhere else in the universe where we could stay alive for ten seconds’. ‘What he’s saying is that it is crazy that we’re even here’, she laughs. ‘And so you want that realisation, not just as children but as adults, that it is actually amazing that we get this time on this planet and we need to appreciate it.’

There does not appear to be a magic formula, and the approach may differ for every author.

In terms of New Zealand children’s authors who present science well, Annemarie credits Gavin Bishop. ‘He’s a genius in terms of how he can communicate something, both in his text and his illustration, and give you the feeling of something quite intense with his combination of illustration and written word.’ There are other great local examples. Giselle Clarkson’s The Observologist is a delightful recent book that entrancingly magnifies the previously unnoticed world of our tinier creatures for younger readers. Botanical artist, author and illustrator Sandra Morris was inspired by the work of her wildlife officer brother to encourage children to celebrate our fascinating native flora and fauna with her captivating books. Maria Gill recommends the work of Ned Barraud and Dave Gunson in bringing our glorious natural history to life.

Maria believes a scientist’s life story told well can empower her young readers. ‘It’s an important part of our history, and the scientists I’ve written about were world famous. I think it’s important to say, “They were kids like you once, they were curious kids, and look what they achieved by being curious and not giving up”.’ She maintains that this inquisitiveness could be the vital spark that leads to a child becoming a scientist one day, or that learning about human rights could result in them potentially becoming a leader in society. ‘With Beatrice Tinsley, the message is that although she was disadvantaged as a female scientist, she didn’t give up either. In fact, she made some difficult decisions that affected her family life, just to carry on with the important work that she was doing.’ Although Maria has discovered that children can be quite aware of issues like gender equality, for others it may be a theme they haven’t heard often, and it is valuable to reinforce it. ‘Just let kids know that they’ve all got potential to achieve something. And that’s why I like nonfiction, although fiction can potentially do the same.’

Just let kids know that they’ve all got potential to achieve something.

Nerissa Cottle is an assistant librarian for Tasman District Libraries, working at the ‘coalface’ and seeing first hand what kinds of books are appealing to young readers. ‘I feel like there is a good amount of interest in science and nonfiction, and I find that there’s certain types of children that gobble it up. Maybe not so much across the board, but the children who are into science and history are very passionate about it.’ Nerissa says books about space and animals are perennially popular, and in terms of history: anything about the world wars. ‘Kids also love reading about famous New Zealanders and our own history, I guess they can relate to it a little more.’ She believes that young readers’ non fiction is more important than ever in our modern electronic information age. ‘Especially with kids using Google so much. They need to learn that not everything they read online is true and real. So I believe the books are so important, you can usually turn to the back to see the sources which the information has come from. And with a book, you can physically hold, see and talk about it.’ Nerissa has witnessed young people writing school reports by simply copying the first thing which pops up on their device screen. ‘I wonder: why haven’t you been taught?’

So if a science-based book is to appeal to a child, what does she believe is an effective approach?

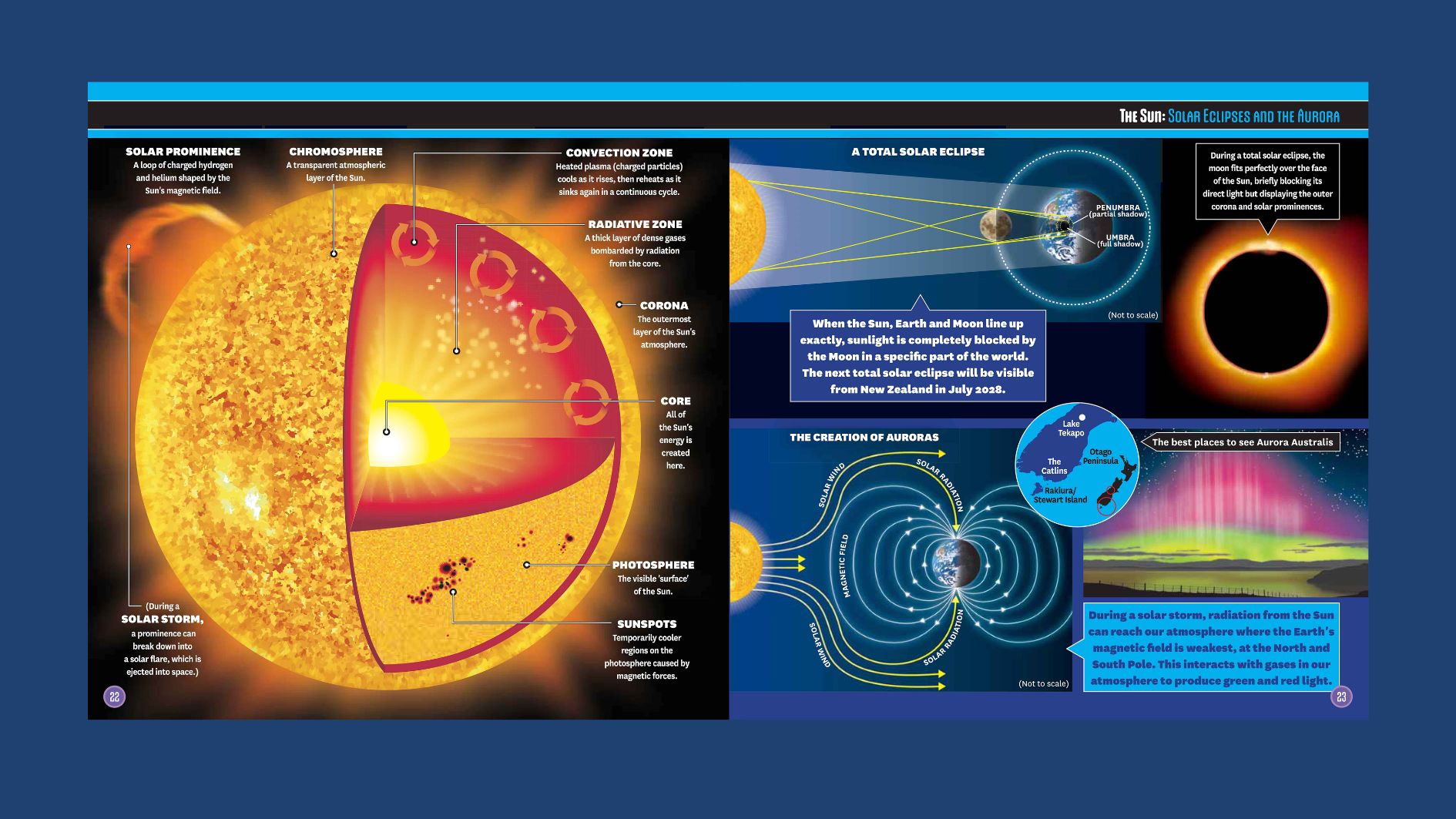

‘Pictures … visuals. My child struggles with reading because of dyslexia. So if she can learn from the pictures, with the writing there to back it up, then that is great. You’ve got to have the information there too. But I’ve seen some young readers nonfiction books that have far too much writing and it’s almost overwhelming. So there’s a real balance to be found between making it accessible, but still accurate.’

It seems that the adage of a picture painting a thousand words still holds true, and information graphics can certainly convey knowledge in ways which avoid screeds of text. Even graphic novels can expand beyond stories about guys in tights beating each other up to deliver important messages. The 2015 graphic anthology Faction Presents High Water saw eleven New Zealand comic artists tackle the consequences of climate change. Also helping to save the Earth (with planet-sized concepts to match), Steve Mushin’s award winning illustrated science and design book Ultrawild fires the imaginations of all ages by exploring the optimistic potential of science.

As a librarian, does Nerissa have any advice for homegrown creators of children’s nonfiction?

‘Anything from a New Zealand perspective is good. Please keep going, you just don’t know how much one of your books could be loved. Because there’s so many different kids out there and sometimes you can have no idea that this one book could just change their life. And it could be the most random book too.’ She adds a last, important, observation: ‘A bit of humour, within context, always helps. Kids do love a laugh, for sure, and those books are often the favourites.’

Kids do love a laugh, for sure …

Elizabeth Preston, former editor of US children’s science magazine Muse, emphasises this point. ‘Kids are people too. They may have a smaller vocabulary than you … .but they like to read something that has interesting characters, drama and maybe some surprise, or humour. They don’t want to read a list of facts about a topic, and if all else fails mention something about Harry Potter.’

As New Zealand publishing contends with another economic downturn, what keeps our nonfiction children’s authors going in the face of hardship? ‘What I gain is the exact thing I hope my readers gain’, says Annemarie, ‘and that is an awful lot of knowledge that stays with me. And an appreciation and understanding for what we have in this world. We all want to know and think about things that matter, it’s pretty humbling really.’ Maria is rising to the challenge. ‘I’m going to be pushing the hashtag: “read local, buy local”. It’s so important that we write and buy New Zealand stories, because otherwise there won’t be a New Zealand book industry.’

Alistair Hughes

Alistair Hughes has illustrated numerous books for New Holland Publishing and Upstart Press, and regularly contributes to various publications around New Zealand. Last year, he wrote and illustrated The New Zealand Night Sky, an introduction for young Kiwi stargazers, and will be following it up in 2025 with a look at our ‘day sky’: New Zealand Weather.Alistair is particularly focused on effectively conveying knowledge to younger readers through text, illustration and graphics.