Nicola Daly is what you’d call a children’s book buff. Officially a sociolinguist and senior lecturer at University of Waikato, she has committed her academic career to children’s literature and language learning. Her latest research looks at how Indigenous voices in Aotearoa New Zealand are, and can be, authentically represented in picture books.

The Sapling (TS): You have recently received a Marsden Grant to explore the role picture books play in Indigenous language, knowledge and identity. What motivated you to undertake this research?

Nicola Daly (ND): Well, I have been researching how New Zealand picture books weave English and Māori text together for the last fifteen or so years. As the years have passed and I have presented my work around the world, I have realised that this is an aspect of children’s literature that is very well developed in Aotearoa. It does happen in other places, but not to the same extent. The motivation for this research has come from a desire to explore, understand more, and showcase the expertise in New Zealand children’s literature around Indigenous language, mātauranga and identity.

TS: Central to this project will be your research with Huia Publishers. What is it about this publishing house that made you want to work with them?

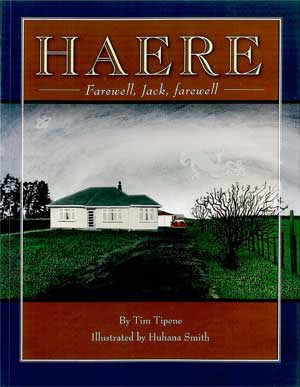

ND: My work began with a book published by HUIA called Haere: Farewell, Jack, Farewell (Tim Tipene and illustrated by Huhana Smith, 2005), which I read to children in my family many times. What I noticed was that the children used Māori words woven into the English text of this book outside of the book. For example, the book uses the word ‘hapū’, and they used this word when they saw a pregnant woman outside of the book, ‘Mummy, is that woman hapū?’. This led to a study of the use of Māori words in English text in eleven picturebooks published by HUIA between 1995 and 2005 and some research with authors and translators about how decisions are made about which words are used. HUIA is a Māori publisher who publish in Māori and for Māori readers, and so I could see that their approach to publishing would come from a Māori world view, and I wanted to know more about that.

TS: Tell us about the team you’ve assembled to do this research.

ND: The team involves four academics and five of the publishing team from HUIA. Between us we have expertise is design (Te Kani Price, Nic Vanderschantz), editing (Bryony Walker), translating (Kawata Teepa, Darryn Joseph), language revitalisation (Julie Barbour) and the publishing process (Eboni Waitere and Pania Tahau-Hodges). We know that in order to bring authentic Indigenous voices through in a picture book you need to consider every aspect of the process from inception, to writing, designing, translating and editing, so our team covers all of these areas.

TS: What is your aspiration for the research? How do you hope it will be used?

ND: Our aspiration for the research is to understand and document the ways in which authentic Indigenous voices can be represented in picture books for our tamariki and to share this knowledge to support the publishing of authentic Indigenous voices in Aotearoa and other countries. We know that when children see and hear themselves in the books they read and have read to them there is much more chance of them being engaged in the magic of reading.

TS: What role do children’s books play in language revitalisation?

ND: They can do this in several ways: by providing reading material for our tamariki and rangatahi in Māori medium education settings such as kura, kōhanga, and wānanga, but also by providing bridges for English speakers learning te reo. All of our English speaking tamariki are learning some te reo Māori in kindergartens and schools. Having books available using te reo Māori or weaving it into English can support that learning. Just like with any new word, when a picture book reader hears an unfamiliar word they have the context of the story and the accompanying illustration to help them work out what it means. Picture books are very powerful for language learning in this way. A colleague of mine, Jacqui Brouwer, and I worked with parents of a kindergarten to explore how parents might use pukapuka with both Māori and English in them to continue Māori language learning at home, and the parents came up with all sorts of ideas about how they might use them and gave us many insights into how their tamariki were using the language they heard in pukapuka in their mainly English medium homes.

TS: Could there be a flow-on effect from this research for other minoristised languages?

ND: Yes, other minoritised languages could also use pukapuka reo rua (dual language picture books) to support language maintenance. My colleague Associate Professor Rachel McKee (Te Herenga Waka) and I looked, for example, at how New Zealand Sign Language is being used in New Zealand picture books.

TS: What propelled you into the field of sociolinguistics? And what is it about children’s literature in particular that keeps you coming back to it?

ND: Because of my immigrant family, I grew up always aware of differences in dialects and accents, and this led me to sociolinguistics, how language reflects society. I also had an amazing teacher, Professor Janet Holmes (Te Herenga Waka VUW), who made sociolinguistics come alive for me in its many facets—sounds, words, syntax, discourse. The power of picture books is that they influence young people in the way they use language and the words and structures they know from a very early age. This makes them particularly engaging for me. To have a form that can have so much influence on future minds, that’s what keeps me coming back.

TS: You are on your own Māori language journey. What has been your biggest takeaway? And what advice would you give to other people considering learning the language?

ND: Yes, I began learning te reo Māori as an eighteen-year-old at the University of Waikato with the well known teacher John Moorfield. I had just returned from an AFS exchange in Thailand, and I had experienced learning to speak another language quite fluently by being immersed in it. I was very aware that there was a language which belonged to my home that I didn’t know, and I wanted to learn more. I remember being interviewed by the news programme Te Karere about why I was learning Māori as a Pākehā. Today I continue my journey with Te Wānanga o Aotearoa and Te Ataarangi ki Tainui. We also have a weekly Reo Parakuihi group (Breakfast language) in my workplace where we meet and speak te reo on a Wednesday morning.

Languages give you insight into whole new world views. I learnt this as an exchange student, and I continue to learn it as I study and use te reo Māori. I have learned that there are huge and important aspects of living in Aotearoa that I was missing through not knowing the language. I still don’t know enough. I am continually learning.

I have learned that there are huge and important aspects of living in Aotearoa that I was missing through not knowing the language. I still don’t know enough. I am continually learning.

If you are considering learning te reo, do it. There are so many courses available. Just sign up. Take a friend with you if you can, so you can practise together. Find picture books to read to your tamariki and moko that weave te reo in and learn alongside them.

TS: When you imagine our children’s book market in twenty years, what do you hope to see?

ND: I think there will be increased awareness of the importance of Māori rangatiratanga throughout the process of publishing of Māori stories—both contemporary and traditional. Also we will see more mita (dialects) in the stories.

Nicola and her colleagues are hosting the biannual Australasian Children’s Literature Association for Research (ACLAR) conference at the Kirikiriroa campus of the University of Waikato from 27–30 November 2024. You can find out more and register here.