Drawing from the philosophical thoughts of children, letting illustration shape words and the life, hard work and love of an illustrator; Nelson-based illustrator Sabrina Malcolm reflects on meeting three international illustrators at their masterclass.

This past September, the windows of Te Auaha Gallery on Wellington’s Cuba Street began to sprout drawings.

It was the start of Picture Me, a celebration of children’s book illustration. The Sapling interviewed Rachel Lawson about Picture Me earlier in the year. In her words: ‘we have shaped our festival around the idea of a picture book as both window and mirror. In a picture book mirror, we see ourselves, where we fit and who we sit with. Through a picture book window, we see the world—it can look the same as our own or very different, but we almost always find that the people (or bears, triangles, pigeons, crayons) have hearts the same as ours.’

The illustrations in a picture book add to its impact—or detract from it—as surely as the words do. As Rachel pointed out, picture books whose characters look like their readers can help those readers visualise their own kid-shaped spot in the world. Beyond that, picture books whose characters look like their readers and who do things their readers had thought impossible for themselves can be transformative. In cultures where good picture books are cherished, their illustrators and writers are cherished too. Surely in those places, more young lives are transformed by picture books.

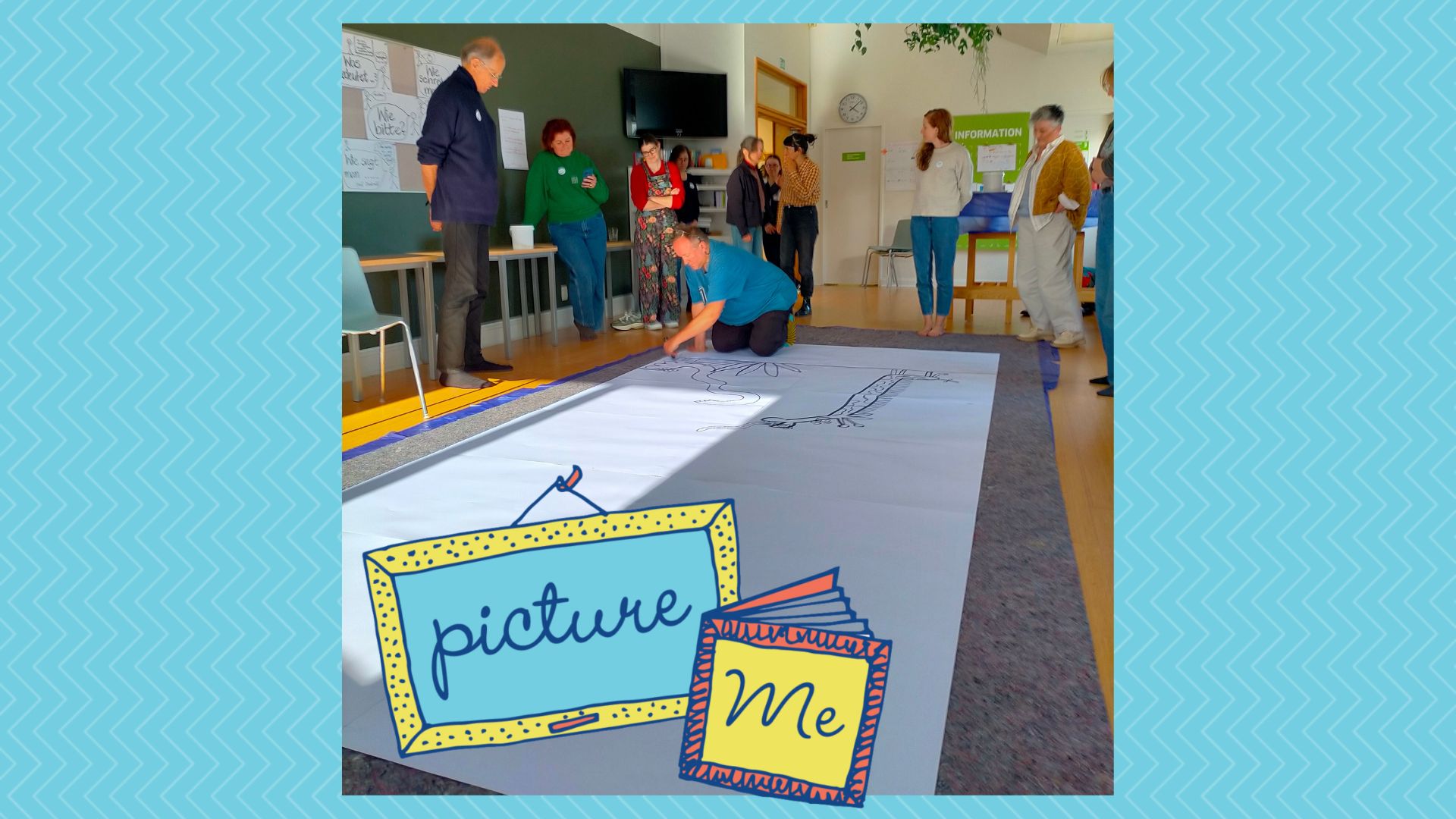

Antje Damm of Germany, Aurore Petit of France, and Piotr Socha of Poland are all award-winning illustrators. Their zest for children’s picture books shines even through jet lag. On Cuba Street the window drawings grew every day, and on the Sunday afternoon of the festival Piotr, Aurore and Antje gave local illustrators a masterclass in illustration. It was a window, and a mirror, of its own.

Whom do you miss?

What do you do that you shouldn’t?

What stories do your parents tell about you?

Antje prompts students at school workshops with questions like these. Children love telling stories about their lives, she says, and it helps them build up a mental image of the space they inhabit in the world.

Antje has been collecting philosophical questions for years. She has hundreds. By making picture books around them, and also around philosophical themes like ‘lies and truth’, ‘time’ and ‘nothing’, she encourages children to ponder. She’s working now on a book about nature that includes the questions, how does winter know when to come? and could trees fall in love with each other?

She believes we should encourage children and trust them to talk about more difficult philosophical themes too, such as human relationships, life, and death. She’s certain they can deal with those topics. She also believes they need to know that everyone, regardless of age, is looking for philosophical answers: adults aren’t a step ahead.

Along comparable lines, Aurore’s picture books focus on important moments, particularly moments in family relationships, that children will recognise. She collects simple shorthand scenes in a notebook as they happen in life: usually social interactions, sometimes an important growing point in a child’s life. Her notebook scenes are sketchy but in colour and include dialogue and/or description. They act as a visual prompt later when she’s looking for a new idea.

Aurore’s own children found Covid lockdowns hard. In the hope of making their situation feel more normal and even (if possible) positive, she made a picture book about it and involved them in the process. It helped them get through, she’s sure. Unexpectedly, their input also affected her own attitudes. Her picture book focus shifted towards simpler ideas and narratives that revolve directly around the child’s world. She has preserved that altered emphasis in her subsequent work.

One of the things Piotr particularly values about making picture books is being part of a change in public consciousness. His research for The Book of Bees taught him that the success of many of our crops depends completely on the success of pollination. He wanted to relay his fascination about that to readers and to show them the impact humans are having on nature.

He also likes to remind students at school workshops that with a bit of looking, they’ll find astonishing things in their own neighbourhoods. What they see in a picture book, he tells them, can be outshone by the marvels found through a magnifying glass in the weedy bit out the back of the garden.

Many of the visiting illustrators’ remarks prompted nods of recognition from the audience.

It was generally agreed that it’s far easier to illustrate your own words than someone else’s and that the less well you know the writer the harder it is. In one case, Antje rang her writer to tell him he’d have to be just as open to changing his words as she was to changing her illustrations. In that case, she reported, it worked well.

All three, out of necessity, augment their picture book income with other work. Those projects are almost solely illustration related—school workshops, for instance, and commercial contracts, and they enjoy them

They’ve all learnt to protect their creative time and mindset. It’s energy sapping to prepare a presentation, travel to a venue and make a public appearance. Worse, it can derail the current train of creative thought. Aurore is looking forward to taking a year off, to focus solely on creating things. And when Piotr first decided to illustrate a picture book, he put aside all other work for the two years it took to complete the book. He, and his publisher, were relieved when it did well.

Antje and Aurore describe their books as almost parts of themselves. People who work creatively, Antje added, reveal some part of their inner self in that work, thereby making themselves vulnerable. It demands some self-assurance. The nodding of the locals’ heads was most vigorous, and accompanied by the most knowing laughter, at any mention from Aurore, Piotr and Antje that they work hard, the hours are long, it’s a solitary and sometimes exasperating business, and that they love it and wouldn’t do anything else. It was a privilege and a pleasure to spend time with them.

On the last Wellington day of the festival, before Picture Me continued on to Christchurch, Te Auaha Gallery hosted a wrapping up party. It served as an opening too: the windows overlooking Cuba Street were now a fantastic tangle of bright, whimsical pictures. Piotr, Aurore and Antje had built up the scene day by day in back and forth dashes between the gallery and festival events.

Festival-goers at those same events, meanwhile, had been building up their own, inner pictures: of the rich world of European picture book illustration, and specifically of the three fine illustrators who lent us their insights and their drawing arms.

Sabrina Malcolm

Sabrina Malcolm is a writer, illustrator and graphic designer. Her illustrations have appeared in children’s books, issues of School Journal and scientific publications.