Pearl D’Silva shares some top tips for picture books around the themes of disability and inclusion, on International Day of Persons with Disabilities.

International Day of Persons with Disabilities (IDPD) is celebrated on December 3 each year. There are over 1.1 million tāngata whaikaha (disabled people) in Aotearoa. I was fascinated to learn that in New Zealand, we use the terminology, ‘disabled person’ instead of the person-first term that is used elsewhere. However, in this piece, I use the term ‘children with disability’ as I explore picture books around the theme of disability and inclusion.

As a parent to a child with a visible, rare skin condition, I was often rattled when people asked me ‘What’s happened to him?’. Or worse, ‘what’s wrong with him?’. ‘They are just curious’, people would advise me … ‘they don’t mean any harm.’ I know that! But as a mum, I often wondered why people ask those questions anyway! As he grew older and could see people stare at him or move very subtly away from him, I started to reflect on how I could support positive and healthy notions of differences and children with disabilities.

The early childhood years are probably the best time to begin shaping young children’s perspectives and attitudes about disability and inclusion. Children notice, ask about, and form ideas and attitudes about social identities during their early years. These include conceptions about different disabilities. Young children are constantly using their working theories and prior knowledge to make sense of what they see. Their knowledge is shaped by how significant adults respond to what’s around them (whether intentionally or unintentionally) and this influences their attitudes and thinking about people with differences. Children may not see others with disabilities around them on a day-to-day basis. So, picture books are an ideal way to give them opportunities to see differences.

Awareness

The first step in understanding inclusion is awareness. Most of us have witnessed a child say something like, ‘Is that a chair on wheels?’, while pointing to a wheelchair. More often than not, the child will be shushed by their parent and their attention is redirected. Normalising disabilities in daily lives is a form of building awareness (especially in the early years). In a way, awareness can present itself through both windows and mirrors.

Initially, I looked for picture books where my son could see himself represented—a skin condition. My first thought was Elmer, the elephant by David McKee who was different because of his colourful patchwork skin. But my son wasn’t an elephant and as he grew, it was hard for him to connect with or see himself in the book. Elmer was a good ‘window’, offering him a glimpse into a world where someone looked different from the rest of their group and a good introduction to the idea that‘It’s okay to be different!’.

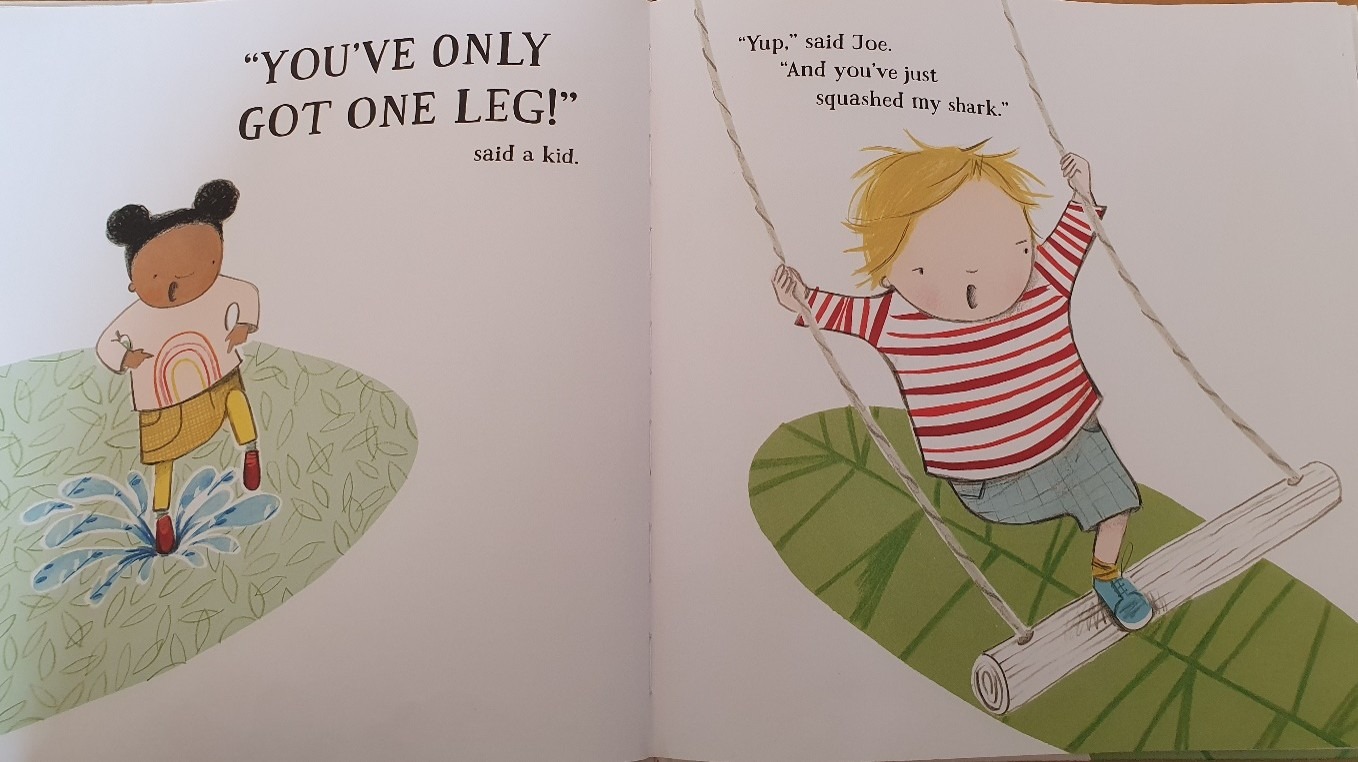

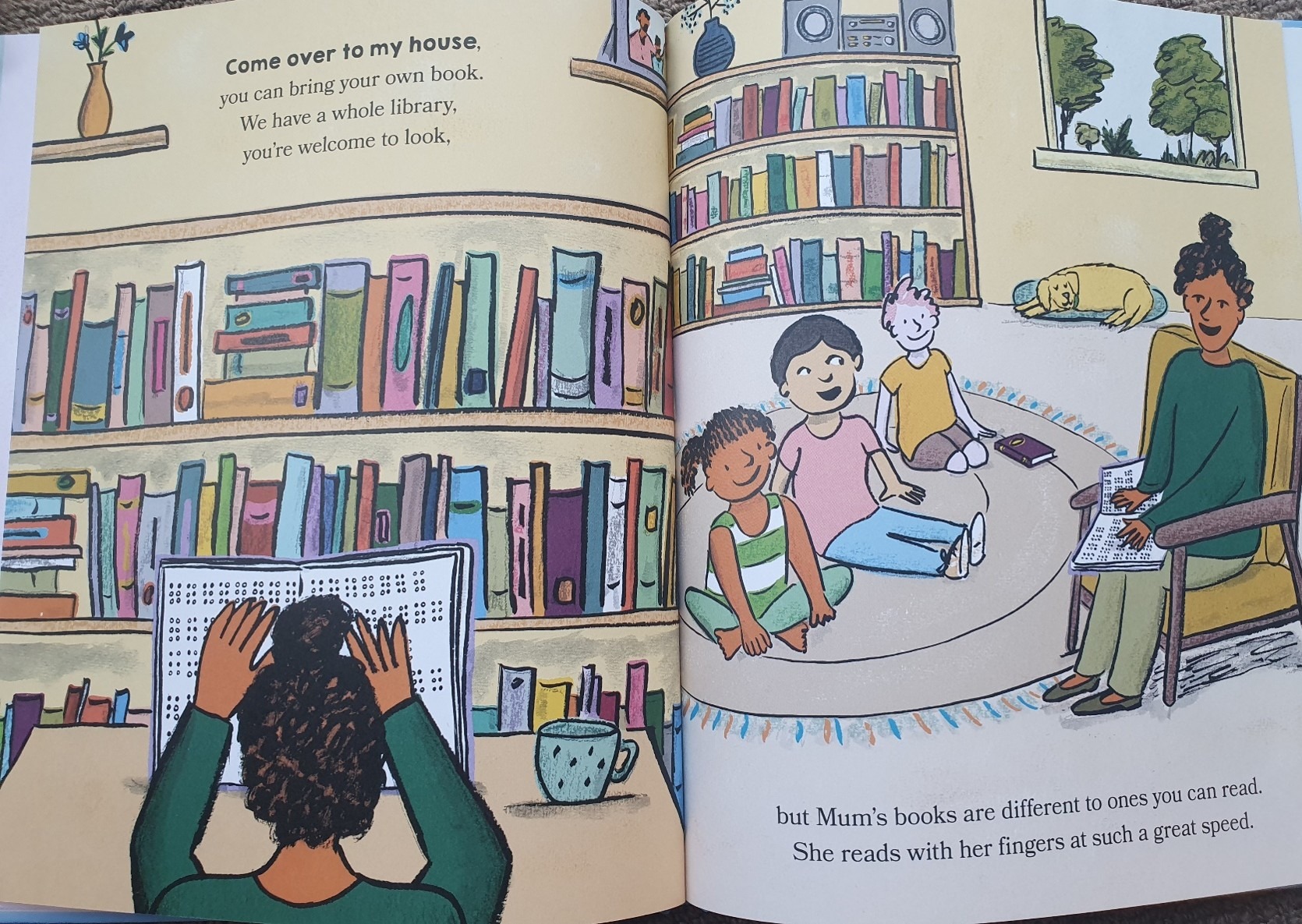

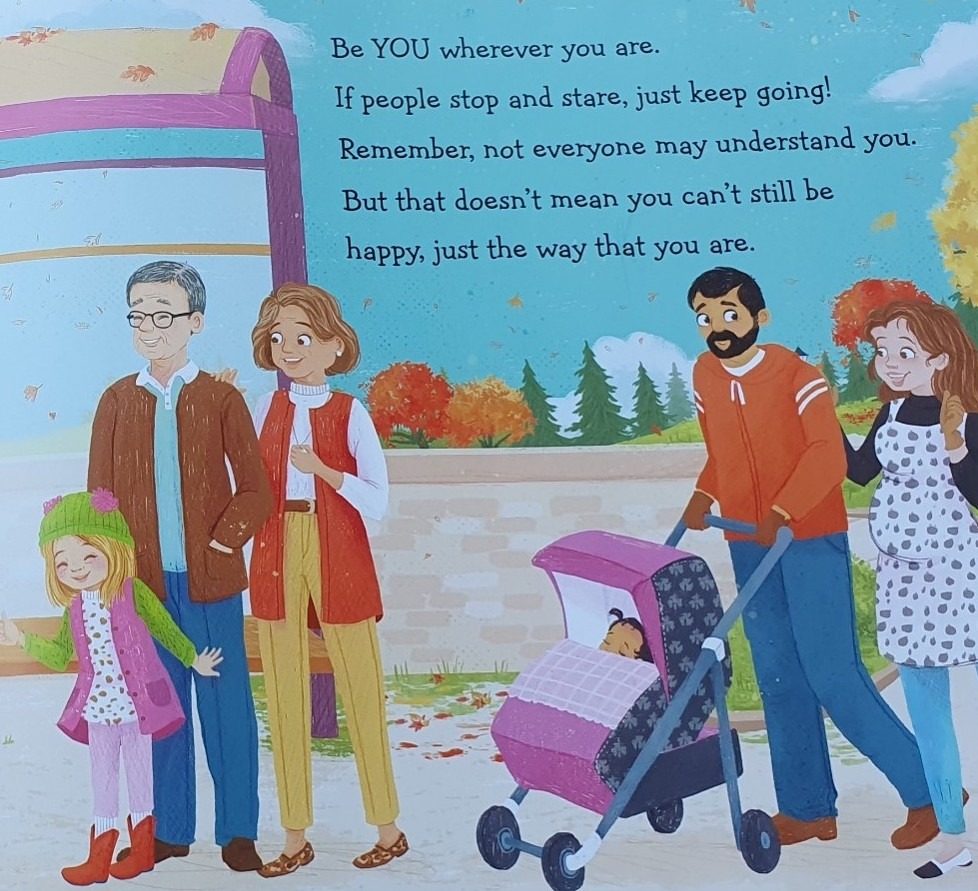

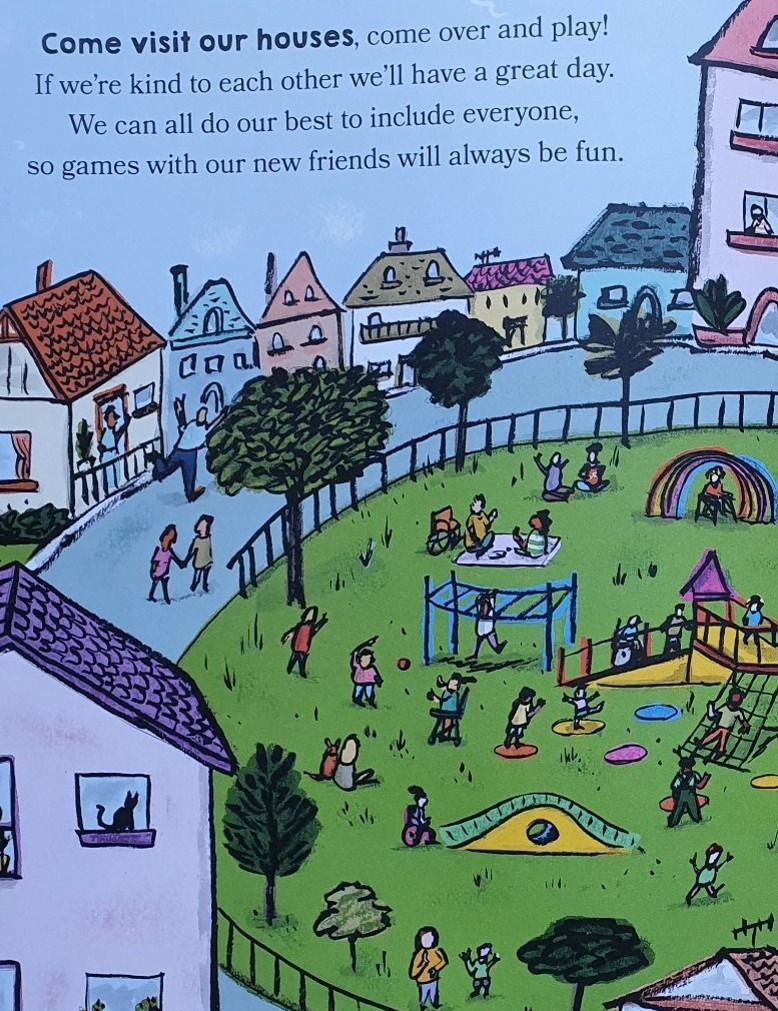

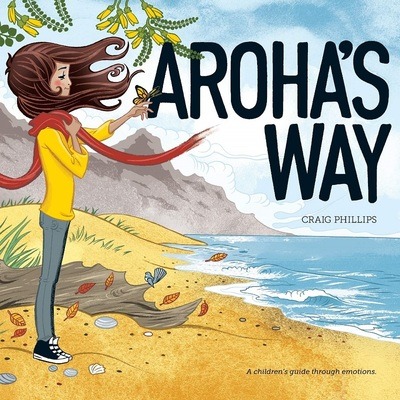

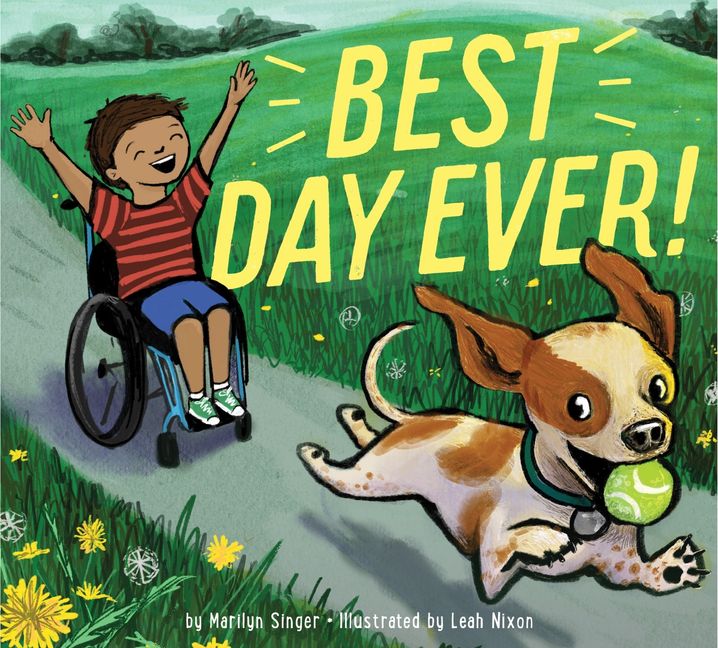

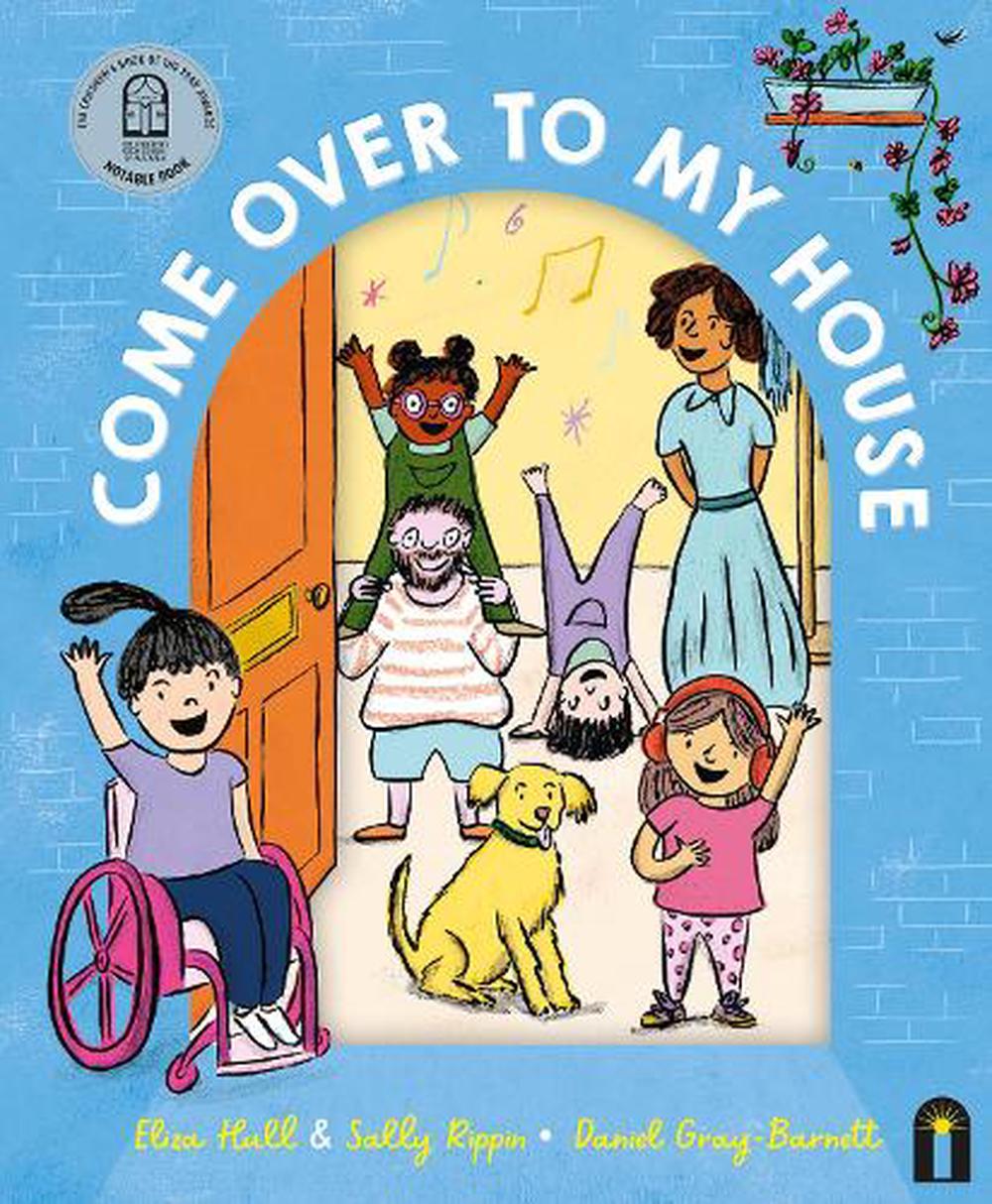

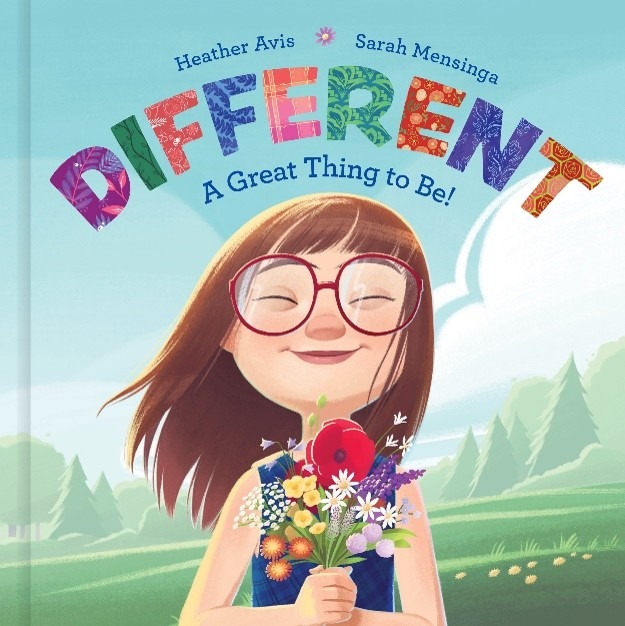

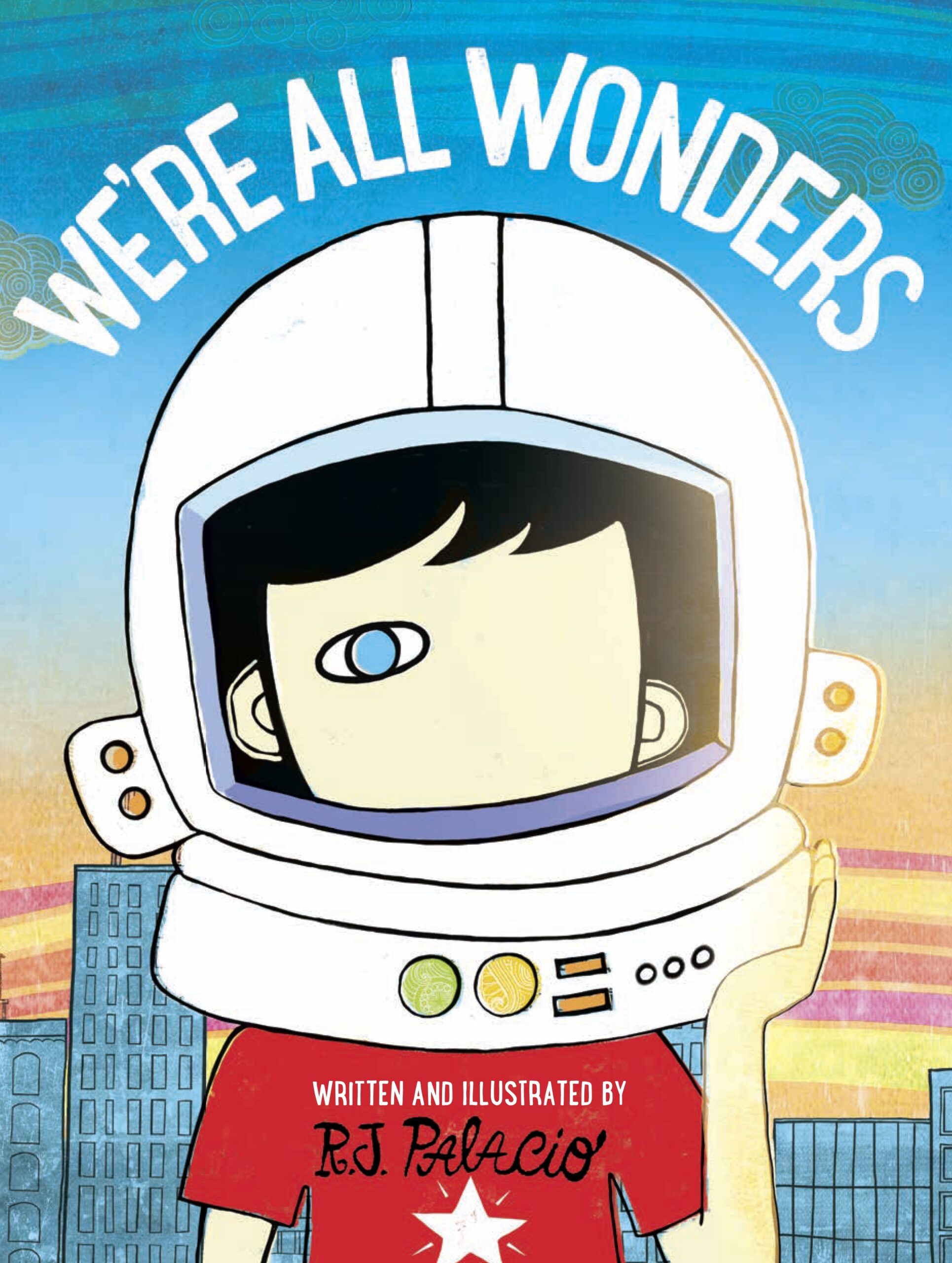

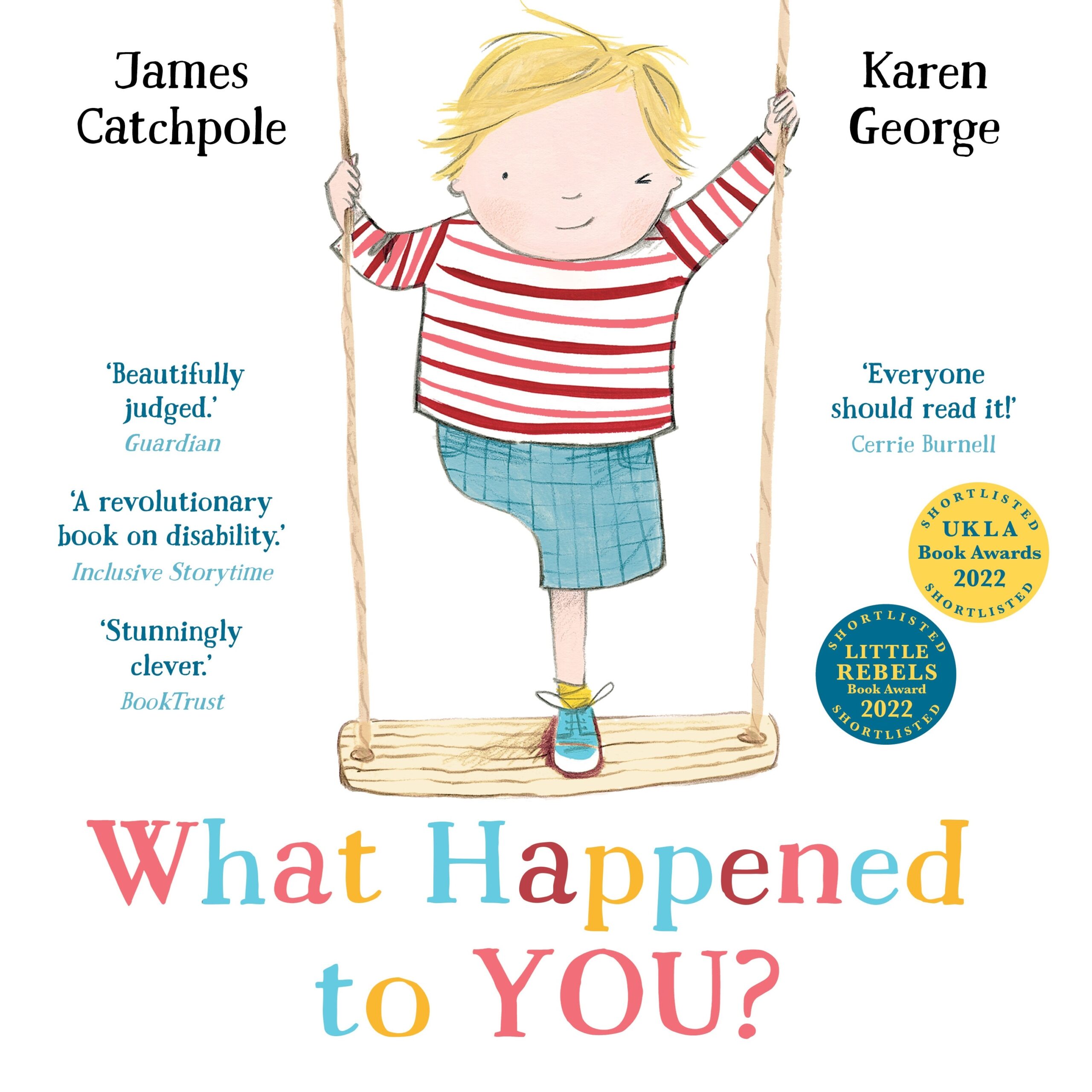

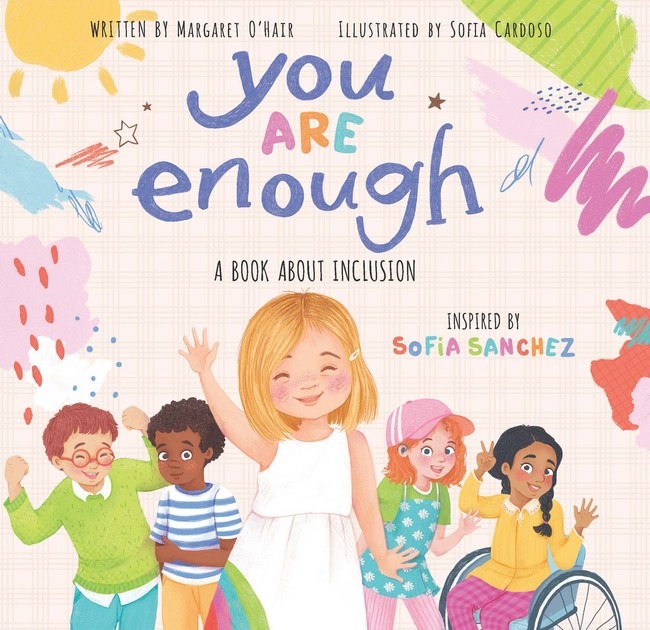

In picture books such RJ Palacio’s We’re All Wonders, Heather Avis’s Different: A great thing to be, Marilyn Singer’s Best Day Ever, Margaret O’Hairs’ You Are Enough: A book about inclusion, Eliza Hull and Sally Rippin’s Come Over to My House, Maria Gianferrari’s Hello Goodbye Dog the protagonist’s disability or challenge is clearly visible through the illustrations and characteristics of either the narration or the text. Picture books like these are one way of helping children develop awareness.

Understanding

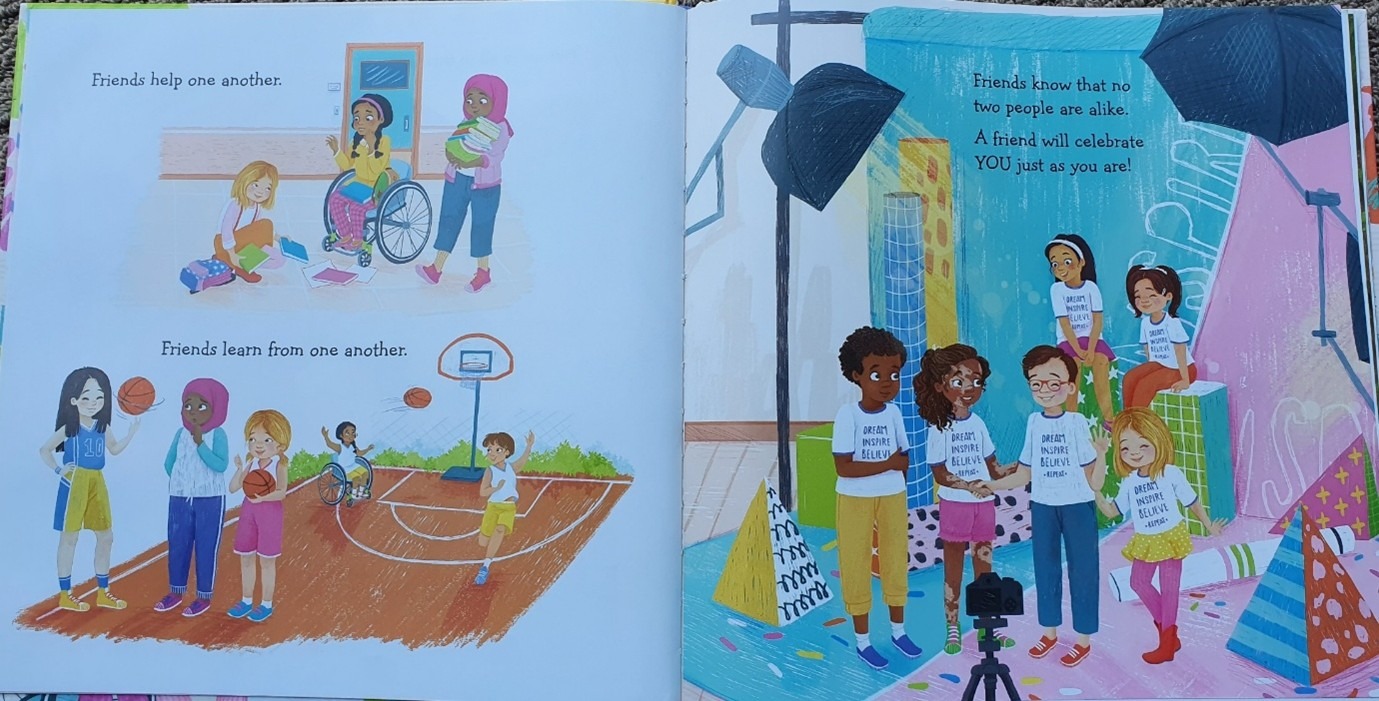

Children’s understanding of disability develops over time, and they need people who can guide their interactions to build positive, accurate knowledge and beliefs about it. Picture books can provide children further knowledge of disabilities and differences. Children who have disabilities or challenges can be supported to make sense of their challenges and their emotions as well as those of others.

For children without disabilities, picture books allow them to explore everyday life, and the challenges faced by their peers—yet again, a window and a mirror perspective.

In my personal experience, I found it hard to find books to support my son’s understanding of his specific condition. Books like Come Over to my House showed different types of disabilities so it helped him understand that there were others who might have different conditions. In the end, I wrote him a story that involved a protagonist with his condition doing ordinary things and that helped him understand that there was nothing stopping him from achieving what he wanted.

By seeing the ordinariness of experiences that the characters in a book have, children can learn that being different does not necessarily mean compromising on what they can do. Readers can learn that they have much in common with children with disabilities. These books can help children develop empathy for others. Books and illustrations can also help children with the right terms and information about disabilities, building their understanding of disabilities and differences.

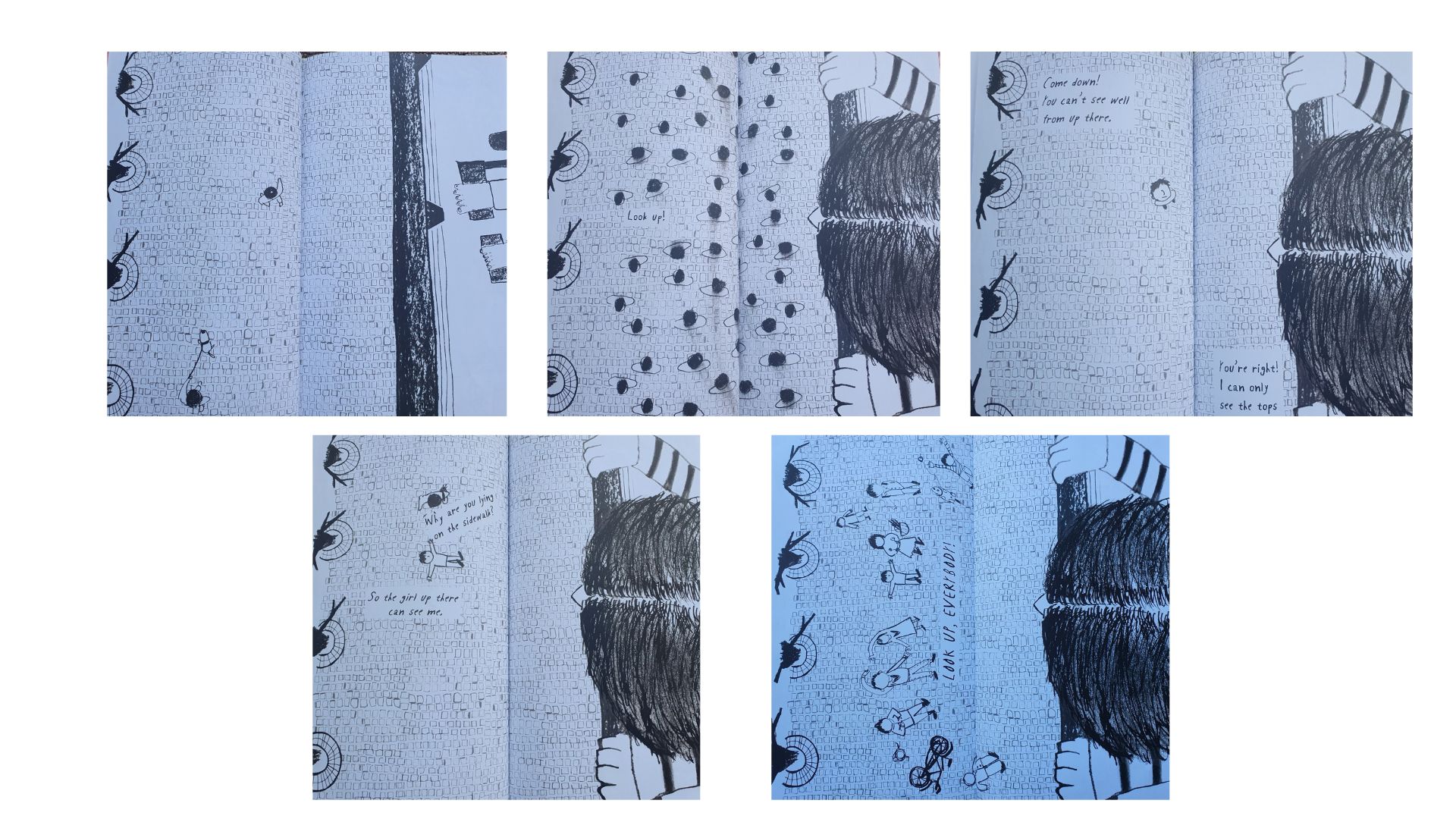

Look Up! by Jin-Ho Jung shows the perspective of both—the child with a physical challenge and the child ‘looking’ into the former’s world. I love how the pictures depict the two perspectives and the solution that the latter comes up with—very childlike and simple, yet so effective!

Acceptance

Sometimes, it may be easy for children with disabilities to develop awareness that they are different from others and acknowledge that they have unique qualities and characteristics. But most often, acceptance is hard and takes a lot of time. This may be especially so in young children who are still developing their cognition and emotional and self-regulation.

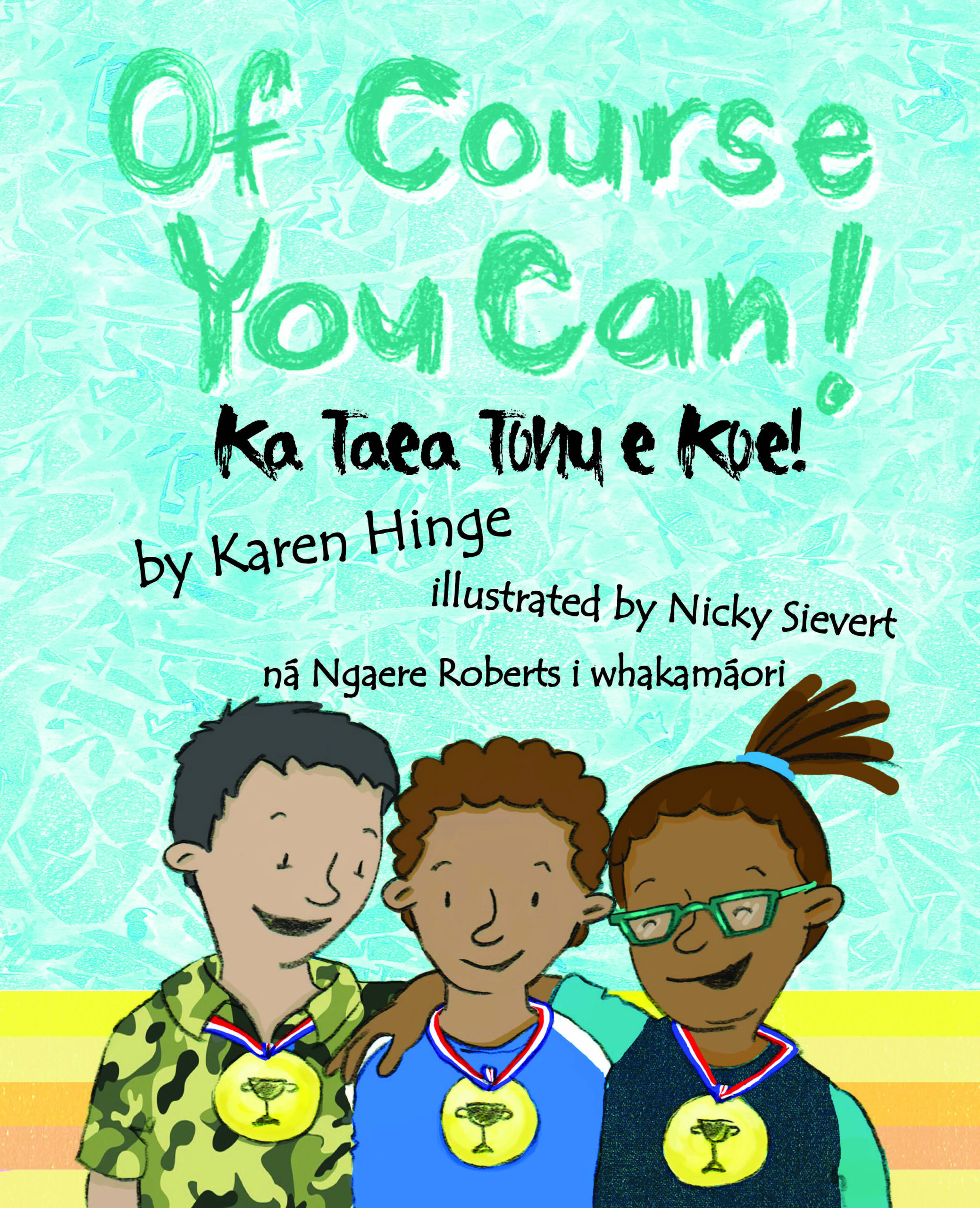

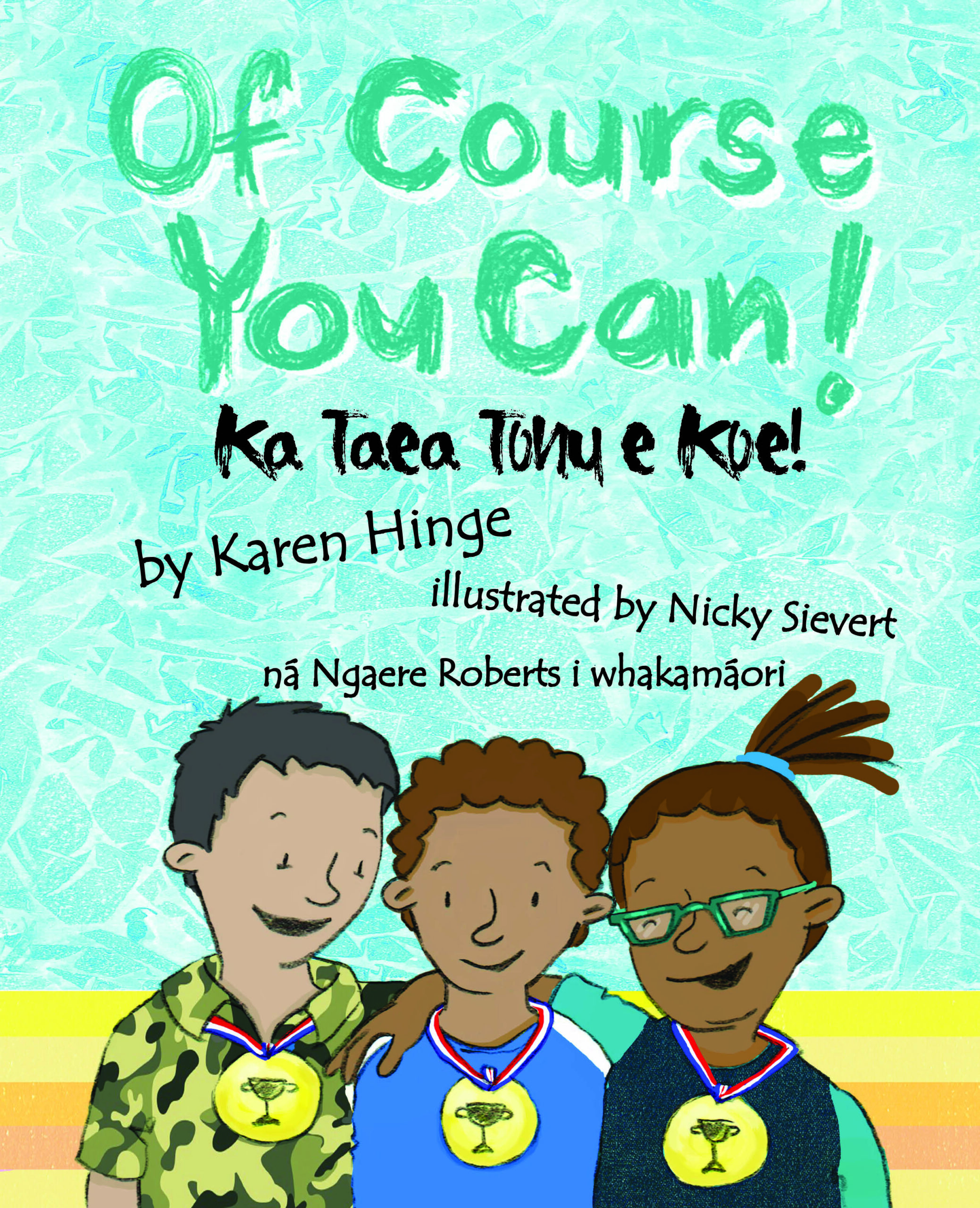

Acceptance is also important from the others’ perspectives. When picture books help build their knowledge and understanding of disabilities, the process of acceptance can be smoother. In almost all the picture books I read, acceptance is found in the form of developing or establishing friendships, wholeheartedly including the child in play and so on. In Of course You Can! by Karen Hinge, the protagonist is shown to be apprehensive about starting school and in his ability to thrive, however acceptance is shown in the form of his peers encouraging him with an ‘Of course you can!’ every time he voices his inability to participate in different experiences.

While acceptance is a never-ending journey, I have seen this evolve over the years (of course, not without its own challenges). As we read and re-visited books like What Happened to You? and the other books in this article, there were new insights that my son developed about his own and other’s conditions which added to his sense of empowerment. Over time, this developed his agency and he could confidently address any questions about ‘what happened to him’.

In picture books where the voice is that of the child who has a disability, you can see threads of acceptance, as they are the bearer of the information and knowledge in the book. They are portrayed as being empowered and in charge of who they are.

Links to Te Whāriki

Picture books can help children experience an environment where ‘they are affirmed as individuals’, as the early childhood curriculum, Te Whāriki, states. Te Whāriki is an inclusive curriculum—a mat for every child to stand on. While the curriculum may be best known by early childhood teachers, it is a relevant lens for everyone involved in young children’s lives and its underlying values and principles are applicable across any setting. If we look at picture books through this lens, we see that the principles of Te Whāriki are interwoven through so many of them.

Empowerment—Whakamana

When children are able to see themselves represented in a book, they feel valued; their mana and rights are respected, and they feel that they are contributing to their own learning. Picture books that promote diversity, such as Look Up! and What Happened to you?, are empowering. For a child who has disabilities to see themselves in picture books empowers them and shows them that they can have meaningful interactions with others and the environment.

Family and Community—Whānau Tangata

Picture books that include whānau and community are always preferable, and more so in picture books that celebrate inclusiveness. In Come Over to My House this is clearly visible in each of the homes illustrated, where whole families are depicted with a range of experiences of the world, and a community housing complex and playground are pictured.

Holistic Development —Kotahitanga

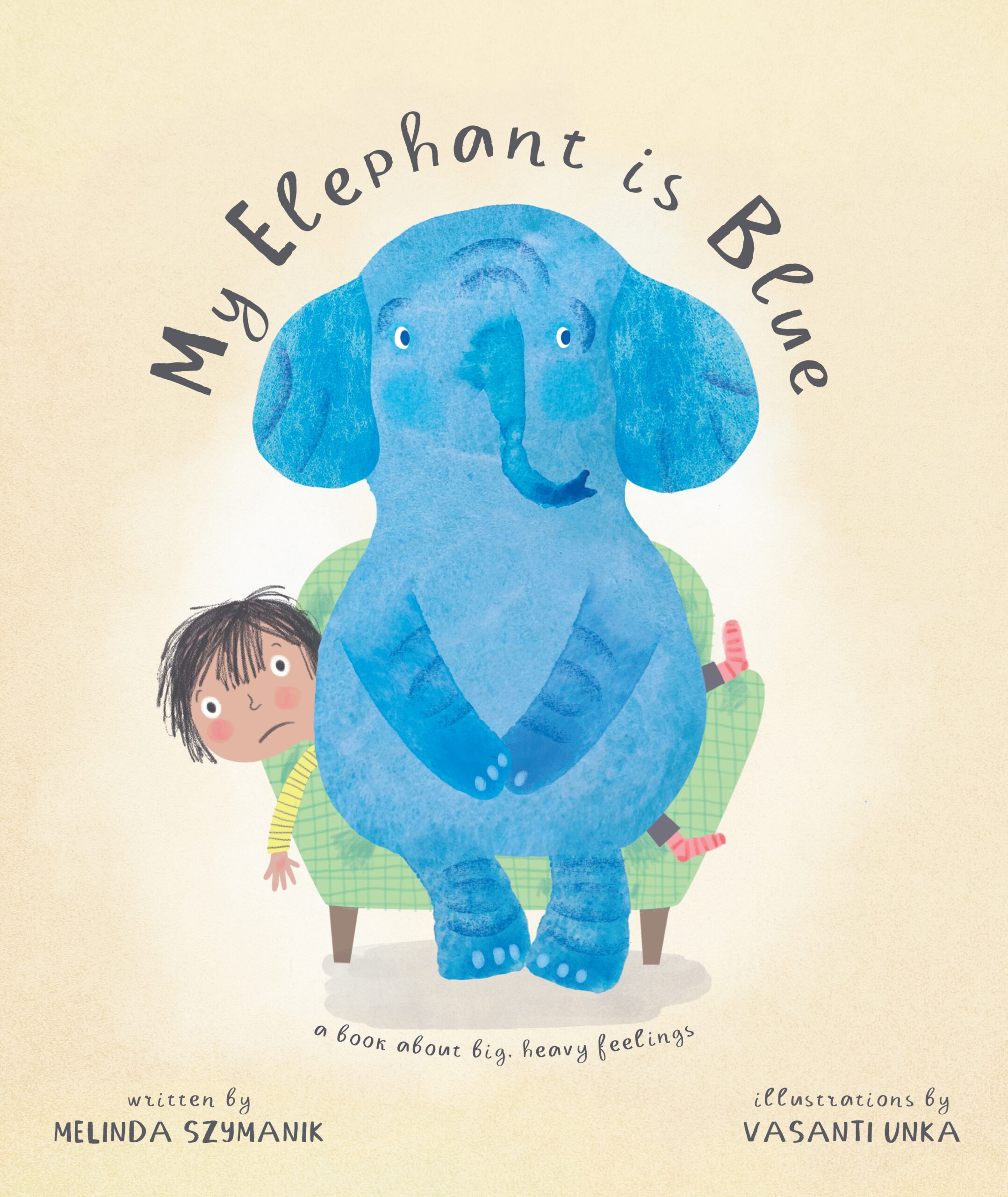

A lot of picture books seem to focus on physical disabilities—I guess it is easier to illustrate them. Yet, there are disabilities sometimes associated with mental health that are invisible and it is important that picture books around these are also available for children. For instance, My Elephant is Blue by Melinda Szyamanik explores anxiety, depression and sadness in children. Hare and Ruru by Laura Shallcrass normalises neurodiversity and picture books by Rebekah Lipp such as Aroha’s Way explore feelings of anxiety.

Picture books show protagonists engaging in a range of experiences holistically. In What Happened to You? we see cognitive development in how the protagonist engages in make-believe play, his emotional development is seen in one of the spreads where he is shown to be sad that children seem to focus on how he lost his leg and in another spread where he is shown to be happy and satisfied at the end that they don’t care anymore. He is shown to build friendships, showing social development, and language development is inherent in his speech. Some picture books show that there are equitable opportunities for protagonists to shine in their own way, such as Fast Slow. Let’s Go! by Sally Sutton.

Relationships – Ngā Hononga

According to Te Whāriki, children are able to develop meaningful relationships with people, places and things. Children learn through active participation in meaningful play experiences, daily routines and interactions with others. Picture books focussing on disability tend to show this positively, thus offering children an opportunity to see that just because a child has a disability, they can still develop friendships and relationships.

Picture books could provide young children the perfect opportunity to develop awareness, understanding and acceptance about children’s disabilities and differences. As windows, they support young children to develop healthy perspectives on differences and inclusion but (and I love this quote from Rudine Sims Bishop’s ‘Windows, Mirrors and Sliding Glass Doors’) with the right lighting, windows can become mirrors

‘So, literature transforms human experience and reflects it back to us, and in that reflection, we can see our own lives and experiences as part of the larger human experience.’.

__

Pearl D’Silva found all of the books mentioned in this article in Auckland City Libraries.

You can find more recommendations from the National Library: Picture Books on Disability and Inclusion

Look Up!

Jin-Ho Jung

Holiday House

Out of print

Of Course You Can!

Karen Hinge

$30.00

One Tree House

Buy now

Also available in bilingual Māori, Niuean, Tongan and Samoan editions

Pearl Dsilva

Pearl D’Silva is an author and children’s literature enthusiast. She is an Early Childhood Education lecturer. She lives in Auckland with her husband, a daughter and son. She can be usually found at the topmost rung of the Ladder on The Faraway Tree, anticipating The Next Land of Adventure!