Sarah Forster reviews two recent YA novels for us—one, a gritty story of overcoming grief and trauma, and the other a time-travelling novel that takes us from 2019 to 1869 and back.

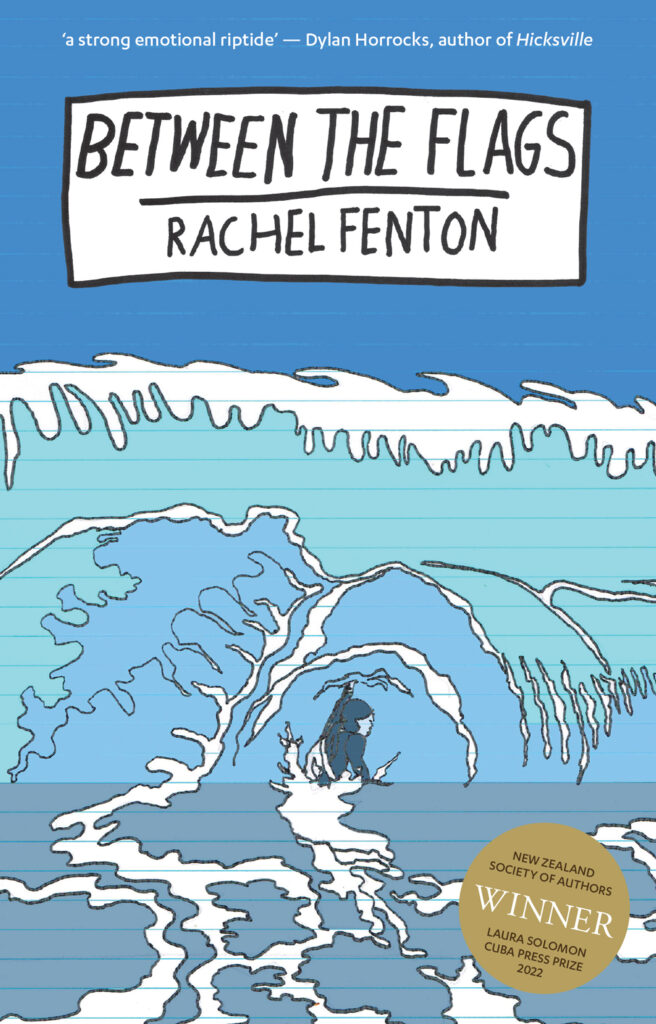

Between the Flags, by Rachel Fenton

CW: bullying, grief, PTSD, eating disorders

This is the story of Mandy Melham. Mandy lives on the North Shore of Auckland, having moved from England when very young. She competes in Surf Life Saving events. Mandy is bullied at school, and at Surf. Mandy doesn’t know her dad, but her relationship with her stepdad is the easiest relationship in her life.

Mandy is grieving. Mandy isn’t talking. And Mandy isn’t eating.

This is a fantastic novel, mixing comics and just astounding writing. It is notoriously tricky to get YA published traditionally, due to the tricky marketing space it is in. But this type of book—particularly this type of book—shows why it is essential to keep publishing for teens.

This is a fantastic novel, mixing comics and just astounding writing

You are with Mandy all the way, compelled to watch intimately as she tries to get back control as everything is falling to pieces around her. The skill with which this story is told sees you spend half of the time engrossed in the story and the other half in frank admiration of the writing. It isn’t dark, despite the topic—Mandy has a wry, relatable humour that comes through in the first-person narration.

Here is a snippet I loved from the start of chapter six. “Mum’s tipping dry pasta quills into a pan when we get home. They ping and bounce and make a piercing sound against the metal until there’s a layer covering the bottom of the pan, then they make a sound like snow crunching under a small gumboot.” Pure poetry.

Mandy is trying to carry on her ordinary life—going to school, doing assignments, reading her assigned text, and side-stepping king bully, Jen—but she hasn’t faced up to her loss. Her teachers range in attitude towards her efforts, with her Classics teacher Ms Givenny doing her best to provide support. Her parents are doing their best, but they have a lot on their own plates. For a long time, the only person that Mandy speaks to is her therapist, Liz.

The book isn’t dark, despite the topic—Mandy has a wry, relatable humour that comes through in the first-person narration

I haven’t got experience with PTSD or therapy, but I’d heard of the techniques explored in this book and have a sense that Fenton knows what she is writing about. The therapy is explained using technical language—it is EMDR therapy, and reference is made to counting things of the same colour to help snap out of flashbacks. I’ve read many YA books that tackle mental health, including suicidal ideation, far too loosely. This is not one of them.

Throughout the book, Mandy is drawing her comics. Sometimes she narrates them to her little brother, explaining her comic in scenes. The comics become the centrepiece of the book and contribute to her growth in an essential way. Mandy draws an Orca—and despite it being a cruel nickname others have given her, it becomes a more neutral motif as the book progresses, with a pod of orcas making a memorable appearance near the end of the book.

My only quibble with the novel is that I lost the sense of time passing as we moved into the second book. I was trying to work out how much time Mandy had taken off school, and that left me adrift for a bit, but as we navigated school prizegiving and the final Surf carnivals, I soon figured it out. The ending is somewhat ambiguous—perhaps a harbinger of another book in the future.

The ending is somewhat ambiguous—perhaps a harbinger of another book in the future

Oh, I nearly forgot my favourite quote, one that echoes what I said earlier. “Writing never feels like being alone, I’m surrounded by my characters. When I’ve been to publishing events for the anthology, or even just at the launch at a bookshop, I’ve seen how much books can mean to people. People like me. We are never alone, not really, so long as we have books and can imagine.”

I highly recommend this for teens. It’s a superb piece of publishing by Cuba Press, and I can’t wait to read what Fenton writes next.

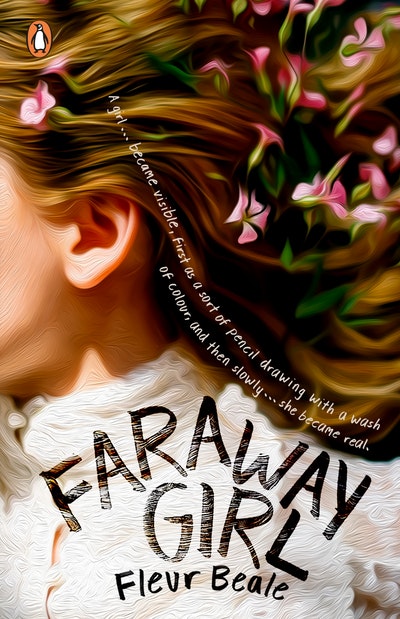

Faraway Girl, by Fleur Beale

What would you do if you were taken out of your comfort zone by 150 years and about 12,000 miles? This is exactly what 17-year-olds Etta from 2019 and Constance from 1869 must contend with in Faraway Girl.

As the novel opens, Etta is feeling helpless. Her half-brother Jamie is fading away, having gone from an energetic, run-everywhere 10-year-old to a zombie-like halfling, stuck somewhere between worlds. She awakes with snatches of memories that aren’t her own intruding on her consciousness—lessons of propriety. She knows her parents are rational professionals, one a lawyer, one a paramedic. She wonders, “Should she tell them about her sense of an undertow in this world?”

The decision is taken out of her hands when Constance arrives at the window, as the family sits down to breakfast. Constance is wearing her 1869-styled wedding gown and has prior to this been sitting for her wedding portrait, for a marriage that is most definitely not for love.

As the novel opens, Etta is feeling helpless…She awakes with snatches of memories that aren’t her own intruding on her consciousness

As Constance arrives, Jamie becomes even sicker, with a planned doctor appointment ending in hospitalisation. The family arrives at the same conclusion as Etta—the two things are related—and then while at the hospital, Etta and Constance disappear from 2019, arriving back in 1869. This is the first of several time changes.

The time travel follows fairly conventional rules—whatever time and place they disappear in 2019, they appear at the same time on the same date 150 years earlier. This means they are often underdressed—while it is summer in Constance’s estate near Manchester, it is winter in Wellington.

Fleur Beale has some common themes in her novels, and one of them is female characters who have a sense of being out of time and place. Juno of Taris was one, as was Esther in her series set in a modern cult, and Molly in The Calling. In this case, the being out of place is more a sense of being out of time, but Etta is no less strong-willed than Fleur’s other characters.

Fleur Beale has some common themes in her novels, and one of them is female characters who have a sense of being out of time and place

I think Etta is Fleur’s most acutely observed modern teen—and that’s saying something. She swears, she is confident and bold, and she is both street-smart and book-smart. She’s also very impatient with the pace of 1869. Etta knows the power of social media, she uses all the tools at her disposal to help Constance in her world, and she is determined to get to the bottom of the mystery of her brother.

I have a sneaking suspicion this may be the first novel of Fleur’s in which the protagonist uses the F-word with impunity, and I love it! Teens swear! This line was particularly satisfying: “Fuck honour! Where’s the honour in how they’ve treated you all your life?”

When Etta disappears for the first time, her parents have the foresight to hire a professional publicist to help with the fallout—I think this is an interesting modern twist on the usual time-slip system where people frequently disappear without comment. If I disappeared in sight of a dozen people, I hope my family would realise the necessity of this. We also have a guest appearance from a journalist called John, with dark-rimmed glasses…

I think Etta is Fleur’s most acutely observed modern teen—and that’s saying something

Constance grows as a character throughout the novel, as she realises there are different ways of living, and that the gender politics of 1869 won’t apply forever. She has long stood up for others, but works out how to stand up for herself in a way that works for her—and Etta gives her space to do this. As a young kitchen girl is dismissed, she stands up to the bully she is meant to marry: “Mr Smeaton, I beg you to reconsider. You speak of immorality but surely it is immoral to condemn a young woman to die of starvation or to turn to the streets to support herself and the child.”

The first three-quarters of the novel have our girls moving between times. The final quarter deals with the loose ends, particularly genealogically speaking (a bewitched portrait is significant here), but it also fills in the backgrounds of Etta’s friends, using this as an indication of how wealth impacts life in modern society.

This is one I’d recommend for anyone who loves historical YA and great story-weaving. Definitely one to put on the list for Christmas.

Sarah Forster has worked in the New Zealand book industry for 15 years, in roles promoting Aotearoa’s best authors and books. She has a Diploma in Publishing from Whitireia Polytechnic, and a BA (Hons) in History and Philosophy from the University of Otago. She was born in Winton, grew up in Westport, and lives in Wellington. She was a judge of the New Zealand Book Awards for Children and Young Adults in 2017. Her day job is as a Senior Communications Advisor—Content for Te Herenga Waka—Victoria University of Wellington.