Nida Fiazi reviews four wonderful new wildlife titles and a must-have activity book for the upcoming summer holidays.

My Little Book of Bugs / Taku Pukapuka iti mō ngā Pepeke by Te Papa (edited by Julia Kaper & Phil Sirvid, photographs by Jean-Claude Stahl)

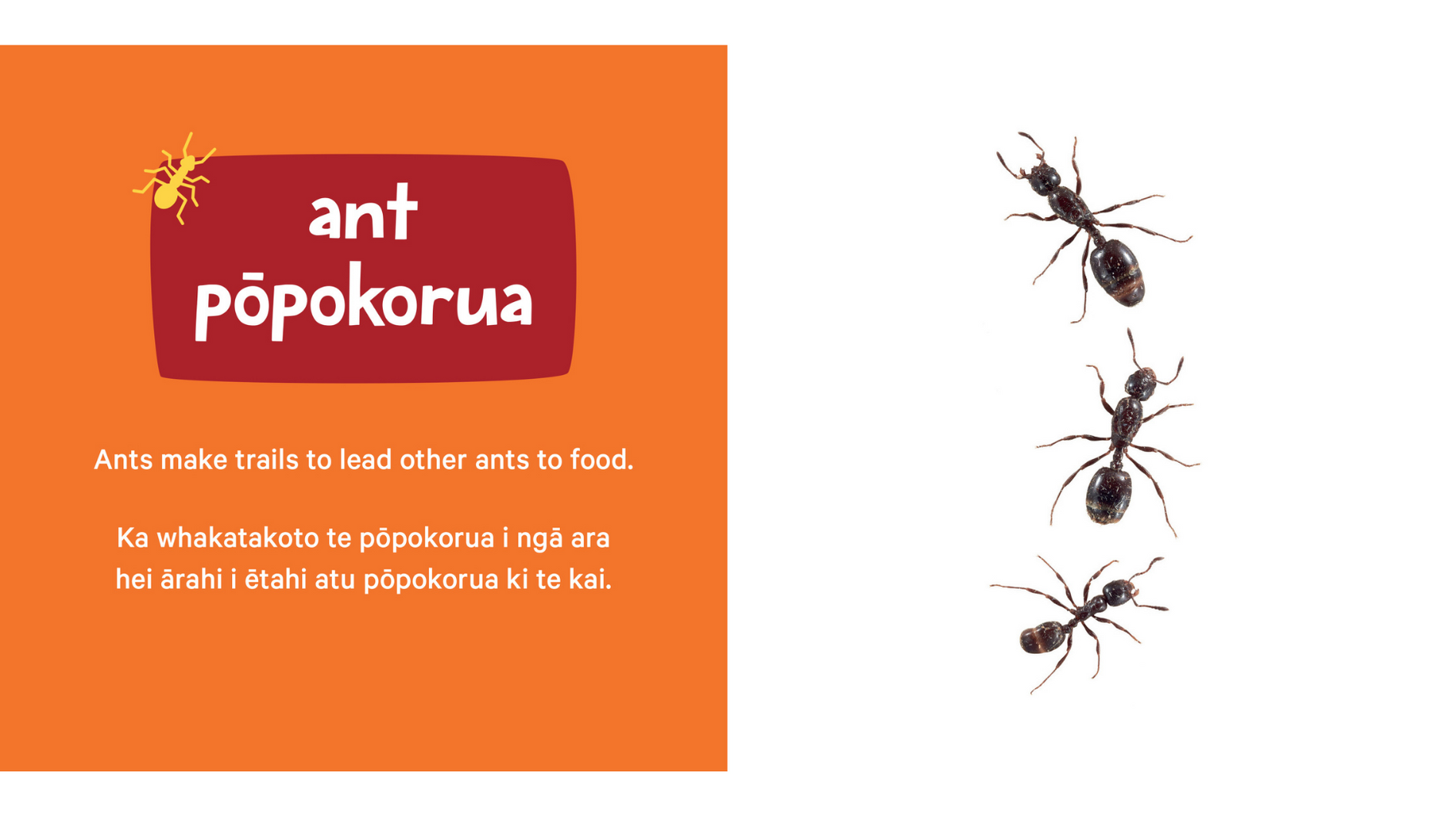

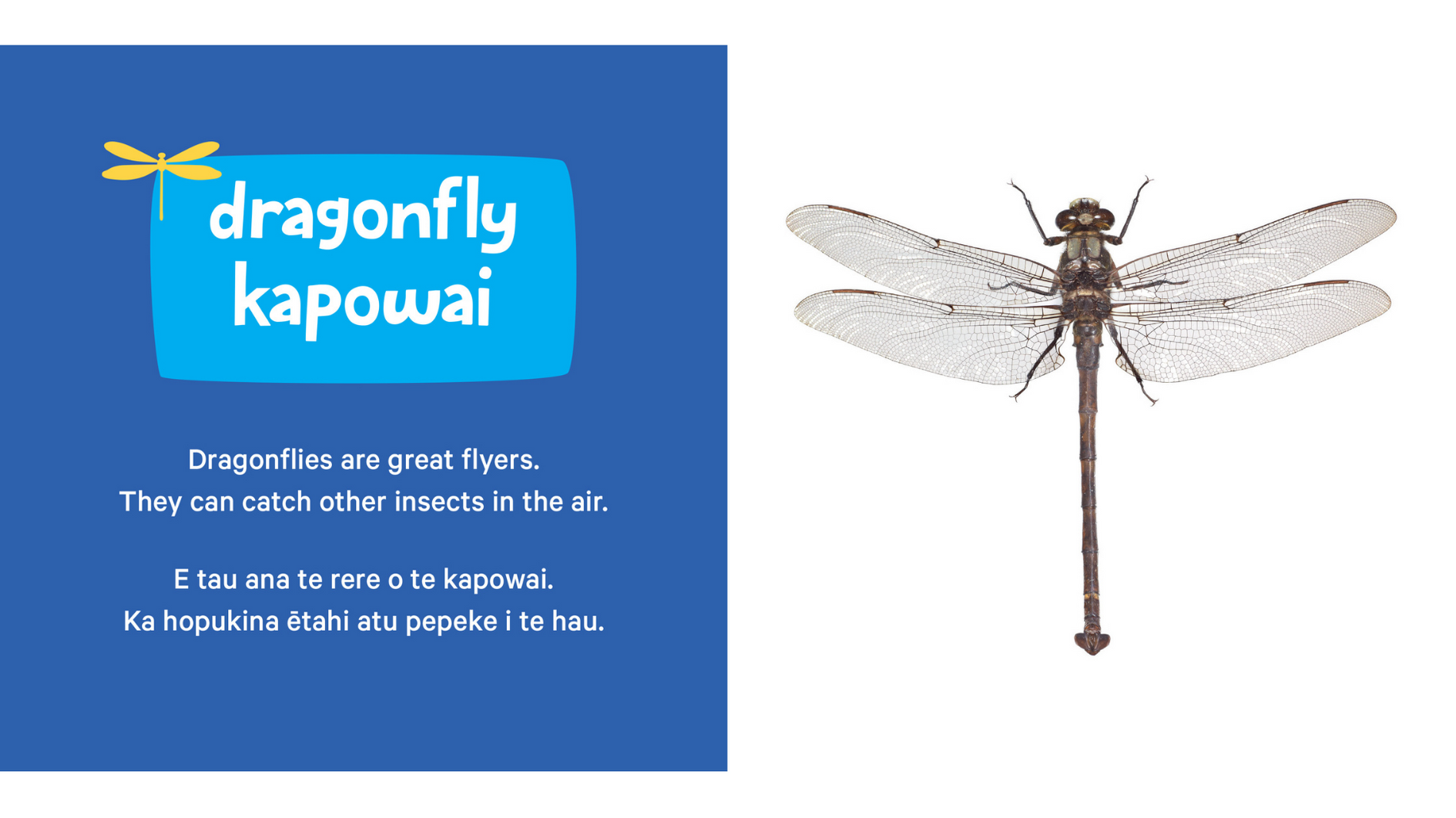

This well-crafted bilingual (Māori and English) board book about Aotearoa’s bugs is a must-have for your little one’s library. Each spread has a photograph of a bug on the right, and the name of the bug in a title box in both Māori and English on the left, accompanied by a relevant fact.

You can find all of the bugs in this book in Te Papa’s collection, so if you’re in Wellington, be sure to head on over to the museum and check out these bugs in person. Until then, brush up on your bug facts from the comfort of your own home.

The bugs are introduced in alphabetical order (English-wise) starting with ant/pōpokorua, and ending with wētā (this is the only page with just the Māori name of the bug in the title box since there is no common English name for wētā). The back of the book also has a grid feature showcasing all the bugs with their scientific and common English names. The Māori names are not included in the grid, but given the fact that the spread is titled ‘What bug is that? He aha hoki tērā pepeke?’, I’d like to think that this was a deliberate choice to reinforce the te reo Māori knowledge readers acquired up to that point.

The design of the book is very clean and appealing. The pages with text alternate between bold green, blue, orange and gold backgrounds, with title boxes in the same colour family. Perched on the top left corner of their respective title boxes are silhouettes of the bugs in a warm shade of yellow. The text itself is in big, clear, white font, that stands out beautifully against the bright backgrounds. The language is simple and age-appropriate. There isn’t any complicated scientific jargon that can potentially overwhelm young readers, though you still might have to explain things like pollen for the little ones who aren’t familiar with those words.

The language is simple and age-appropriate. There isn’t any complicated scientific jargon that can potentially overwhelm young readers.

Jean-Claude Stahl’s astonishingly detailed photographs aren’t just beautiful to look at, they’re also great for developing visual literacy in children who haven’t learnt how to read yet, and helping improve reading comprehension in those who have. Each bug is positioned right in the middle of the page, against a stark, white background, making them the main point of focus. So when children learn that ‘grasshoppers have their ears in their legs’, they can look straight at the photograph to see for themselves where these strange leg ears are. I definitely spent a good few minutes having a staring competition with the red admiral butterfly, trying to see if I could make out their scales after finding out that ‘butterfly wings are covered with thousands’ of them.

This book is pitched at preschoolers but I think it’d be an awesome language aid for te reo Māori learners of all ages, or even a language aid for English learners! My Little Book of Bugs / Taku Pukapuka iti mō ngā Pepeke would also be a wonderful educational tool in any pre/primary school environment.

My Little Book of Bugs / Taku Pukapuka iti moo ngaa Pepeke

Edited by Julia Kaper & Phil Sirvid

Photographs by Jean-Claude Stahl

Published by Te Papa Press

RRP$19.99

Whiti—Colossal Squid of the Deep by Victoria Cleal, illustrated by Isobel Joy Te Aho-White

This hardback non-fiction picture book transports us to Antarctica to follow colossal squid Whiti on her journey from hatching out of an ant-sized egg to becoming one of the largest invertebrates on the planet. Along the way we meet other creatures in the Ross Sea, such as glass sponges, and ribbon worms, and learn about how our national museum Te Papa came upon its most popular attraction—their display of the world’s first intact colossal squid.

The language in this book is conversational yet informative. Victoria weaves in words and phrases that are more common in fiction such as ‘uh-oh!’ and ‘phew, that was close’ amongst the facts, and even finds ways to include fun onomatopoeia to help make the facts easier to digest. She also uses rhetorical questions like ‘see how the ice is a greenish colour underneath?’ and ‘can you spot them?’ to engage the reader and invite them to seek out what the text is describing.

Many pages use fact boxes to introduce the different kinds of animals and plants in Antarctica, as well as separate bodies of text (with their own headings) containing information (in a different font) that may not be directly relevant to what is discussed in the main text, but serve to expand the reader’s knowledge about the overall region – like the fact that octopuses have eight arms and no tentacles! There’s also a glossary at the end which offers definitions for the more difficult scientific terms.

One of the things I noticed and appreciated right off the bat was the integration of, and importance placed on, te reo Māori in this book. Māori names and terms such as Papatūānuku (earth mother), mauri (life force), ika (fish), and karu (eyes) are woven throughout the text whenever possible. They’re only translated the first time they appear, allowing for those words to become part of the readers’ personal vocabulary by the end of the book. Readers can refer back to the glossary, which has a section listing all the Māori words that show up in the book, if needed.

I also really liked how both Victoria and Isobel incorporated te ao Māori into this book. One of the main themes in Whiti—Colossal Squid of the Deep is that of Aotearoa and its people’s role as kaitiaki (guardians) of Antarctica. Victoria also mentions the connection Māori have to whales when discussing Whiti’s main predator—pāraoa (sperm whales) – and dedicates half of the final page to a Māori myth—the tale of Kupe and Wheke (the giant octopus). A koru motif can also be seen on the cover and throughout the book.

I knew I was in for a treat the moment I spotted Isobel’s name on the cover. Her vibrant art style has become one of my favourites this past year, and for good reason. The illustrations, despite being grounded in realism, are brimming with character, and the maps and diagrams are very detailed and clearly well-researched. Three gatefolds allow for a panoramic view of the deep sea, and for a proper comparison of the giant squid and the colossal squid (across four whole pages!).

The illustrations, despite being grounded in realism, are brimming with character, and the maps and diagrams are very detailed and clearly well-researched.

If I had to pick a favourite illustration, it would be the spread featuring the lanternfish and Whiti’s bioluminescent karu in the deep sea. I don’t know how Isobel managed to make a 2D image glow, but she did and the outcome is mesmerising. Since this is a book about Antarctica’s marine life, there aren’t many humans featured in the illustrations but the few that are, offer a fairly decent representation of New Zealand— something I observed, and really liked about Isobel’s previous work.

Whiti—Colossal Squid of the Deep belongs on the shelves of every school, public, and home library in Aotearoa.

Whiti—Colossal Squid of the Deep

Written by Victoria Cleal

Illustrated by Isobel Joy Te Aho-White

Published by Te Papa Press

RRP $29.99

Amazing Aotearoa Activity Book by Gavin Bishop

This activity book is the perfect follow-up to Gavin’s award-winning nonfiction books Aotearoa: The New Zealand Story and Wildlife of Aotearoa. It has more than 60 different activities (inspired by the content in the aforementioned titles) celebrating our nation, its history, people, language, culture, and wildlife.

There’s so much to learn and do in this book, from creating your own imaginary country, to inventing your own mode of transportation, and designing your own house. There are also plenty of other activities like maths puzzles, spot the difference images, and crosswords/wordfinds that will keep your brain active on the days you’re not feeling up to creating. One thing’s for sure, Amazing Aotearoa Activity Book will keep every member of the family occupied for hours over the summer holidays.

I like the simple and straightforward language that Gavin uses in this book— the text isn’t dumbed down, but rather carefully crafted to be accessible to children of all ages (adults too!). The illustrations are in the same signature style and colour palette as his previous Aotearoa books, and they just serve as further evidence that whether it’s people, food, vehicles, houses, clothing, wildlife, or Māori gods and mythical creatures—he can draw it all.

The activities require you to work to uncover the facts through things like fill in the blanks, and crack codes rather than spoon-feeding them to you. It’s a sure-fire way to make new concepts actually stick in my mind, and not float up and away the minute I flip over to another page. Even the activities that seem a bit random at first (e.g. a career quest) are prefaced with facts about our country. In this instance, post WWII, returning soldiers needed to find employment but their options were limited because ‘Aotearoa’s job opportunities came mainly from its natural resources and food production’.

In terms of the content, Gavin doesn’t delve too deep into the details of our nation’s dark history but he does acknowledge significant historical events such as the signing of the Treaty, protest movements, and land wars amongst other things. The adorable little joke bubbles he fit in and around the other activities are omitted from the pages that discuss these heavier topics, out of (what I assume to be) respect.

The activities require you to work to uncover the facts through things like fill in the blanks, and crack codes rather than spoon-feeding them to you.

I probably sound like a broken record at this point, but I genuinely appreciated the incorporation of te reo and mātauranga Māori in this book. ‘Aotearoa’ is used instead of ‘New Zealand’ throughout the entire book when referring to our country. There are entire pages dedicated to Māori culture, mythology and historical figures (e.g. draw your whānau, share your whakapapa through a pepeha, guess the Māori atua [gods]). Māori words are sprinkled in wherever possible— these are sometimes translated (e.g. ‘Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa’ = ‘The Pacific Ocean’) but not always. Despite that, you can usually figure out the definitions of the Māori words through context clues. For example, the word pā was new to me but I got the gist of its meaning because of how it was used: ‘his pā was so ingeniously designed with a maze of trenches, towers and bomb-proof shelters that it was thought unbreakable’. There were still a few words I struggled to decipher on my own, but rather than viewing this as a hindrance, I felt motivated to do my own research because as someone who considers Aotearoa as my home, I should know!

One final thing to note: if you get stuck, most of the answers are on the last five pages. Now that you know that little tidbit, forget I said anything and go buy the book for yourself!

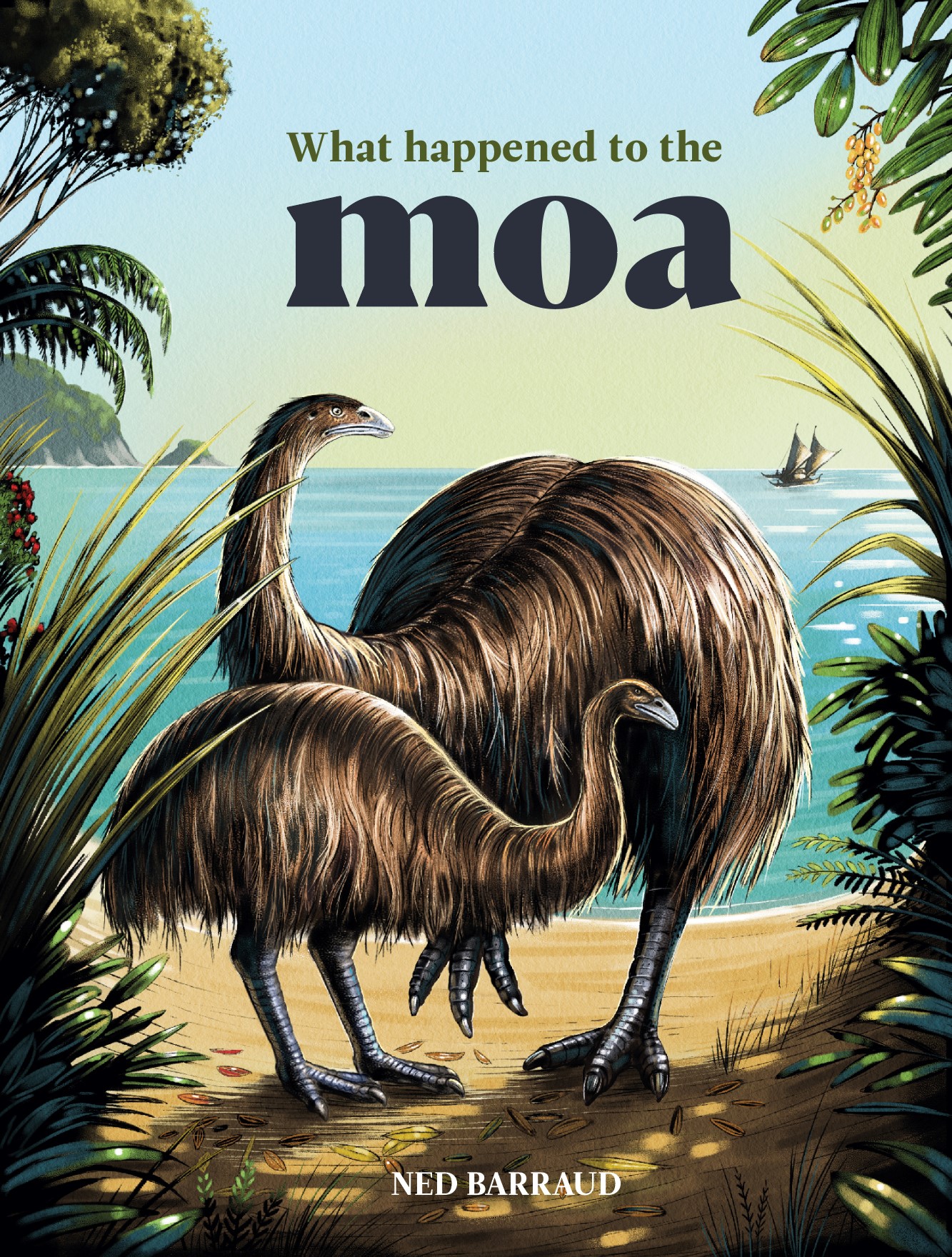

What Happened to the Moa? by Ned Barraud

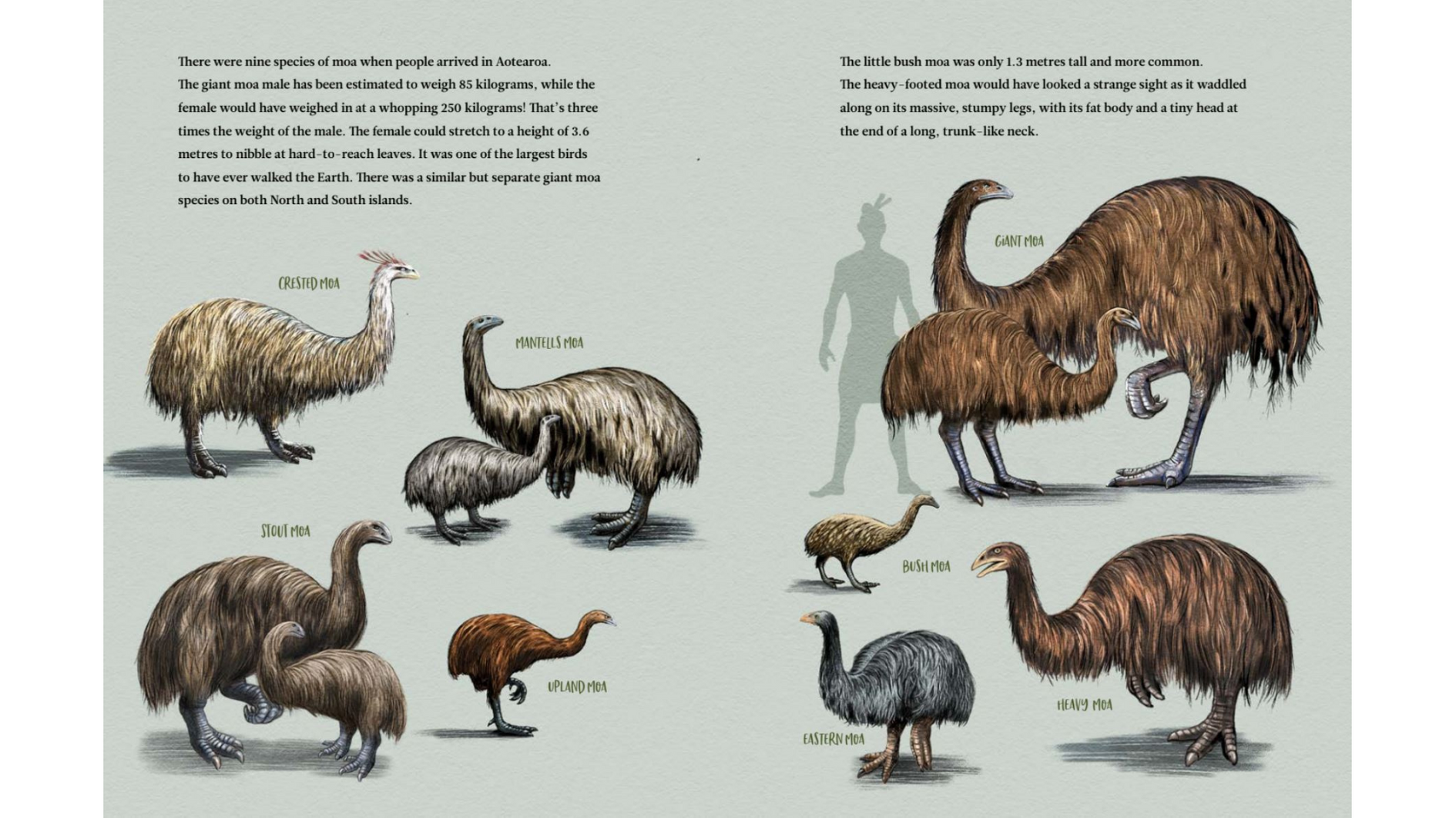

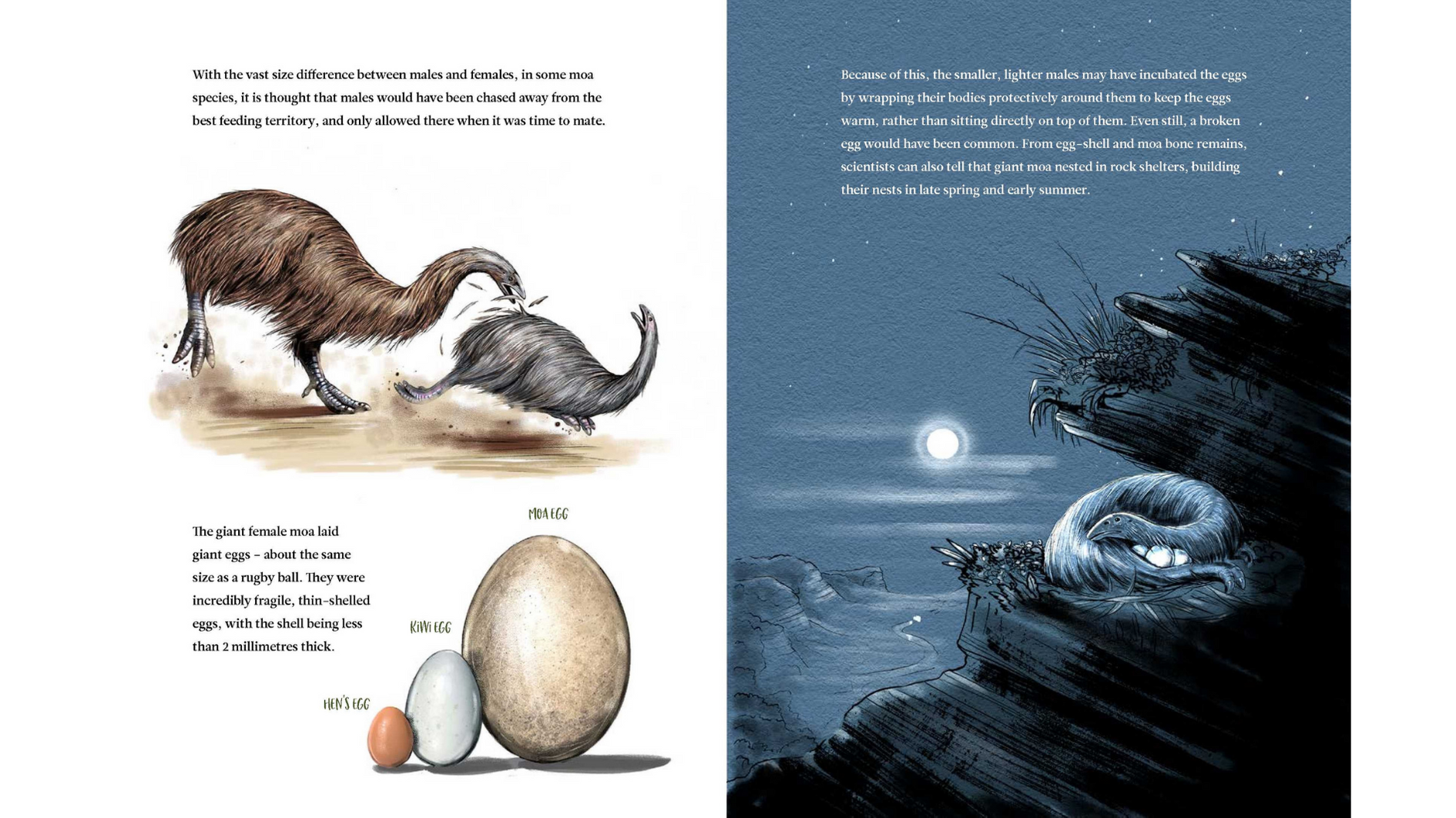

Inspired by the discovery of moa footprints in a Central Otago riverbed in 2019, the first of Ned Barraud’s two books launched this October explores the story of this remarkable flightless bird. What Happened to the Moa? takes us on a prehistoric journey to meet nine different species of moa, and learn about where they came from, what they looked like, how they lived, their main predators, and their eventual extinction. The book debunks common myths associated with this legendary bird (that they’re closely related to the kiwi), discusses their encounters with humans, and even examines the last claimed human sighting of a moa in 1880.

Ned uses approachable and friendly language but manages to retain a formal tone by writing in the third-person. Whenever a scientific term like ‘gizzard’ is introduced, it’s explained in the text using verbal and visual comparisons readers will likely already be familiar with, like ‘a specialised, muscular stomach’. This is great because there isn’t a glossary or index at the end of the book so it’s vital that readers are able to decipher the content through the text and illustrations alone. Although the book is packed with facts, it’s not difficult to read because the information is woven into one chronological narrative— no fact boxes or asides to distract you from the story here.

If I know anything about Ned from his previous work, it’s that he does not shy away from difficult topics like death, and this book is no exception. There is a slightly gruesome and bloody spread depicting humans butchering moa, as well as some potentially upsetting imagery of moa running from human-caused forest fires and getting stuck in the peat layer of lakes (where they would eventually die). Due to the graphic nature of this kind of content, in an unusual move, Ned himself has recommended What Happened to the Moa? for those above the age of nine.

The illustrations closely resemble the realistic art style and natural colour palette of Ned’s previous non-fiction books with Potton & Burton. I personally found the detailed and labelled diagrams of the moa skeleton/skulls, the magnifying glass feature on the page about horoeka (lancewood), and the use of humans as a scale of measurement throughout the book to be wonderful and enriching additions to the text. You can tell just by looking at the final product that a lot of thought, care and research has gone into it.

The former anthropology student in me absolutely loved the little snapshots into historical Aotearoa—the waka, houses, clothing, and hāngī were just stunning to look at. I couldn’t help but notice though, that the word Māori was only used once in the entirety of this book when referring to the people native to this land. All other times, the umbrella term ‘Polynesian’ or even more generally ‘humans’ was used. I understand that the latter terms might’ve been more accurate to use when describing the arrival of the first humans to Aotearoa, but don’t see why these weren’t later replaced with the word ‘Māori’. It’d be interesting to know what the thought process behind this decision was, especially since the non-Māori were all labelled as specifically British or members of a settler family.

You can tell just by looking at the final product that a lot of thought, care and research has gone into it.

I can see What Happened to the Moa? being an invaluable resource in educational settings (as well as at home). More than anything, I’m just glad we finally have a non-fiction children’s book dedicated to one of our most famous birds.

Where is it? A Wildlife Hunt for Kiwi Kids by Ned Barraud

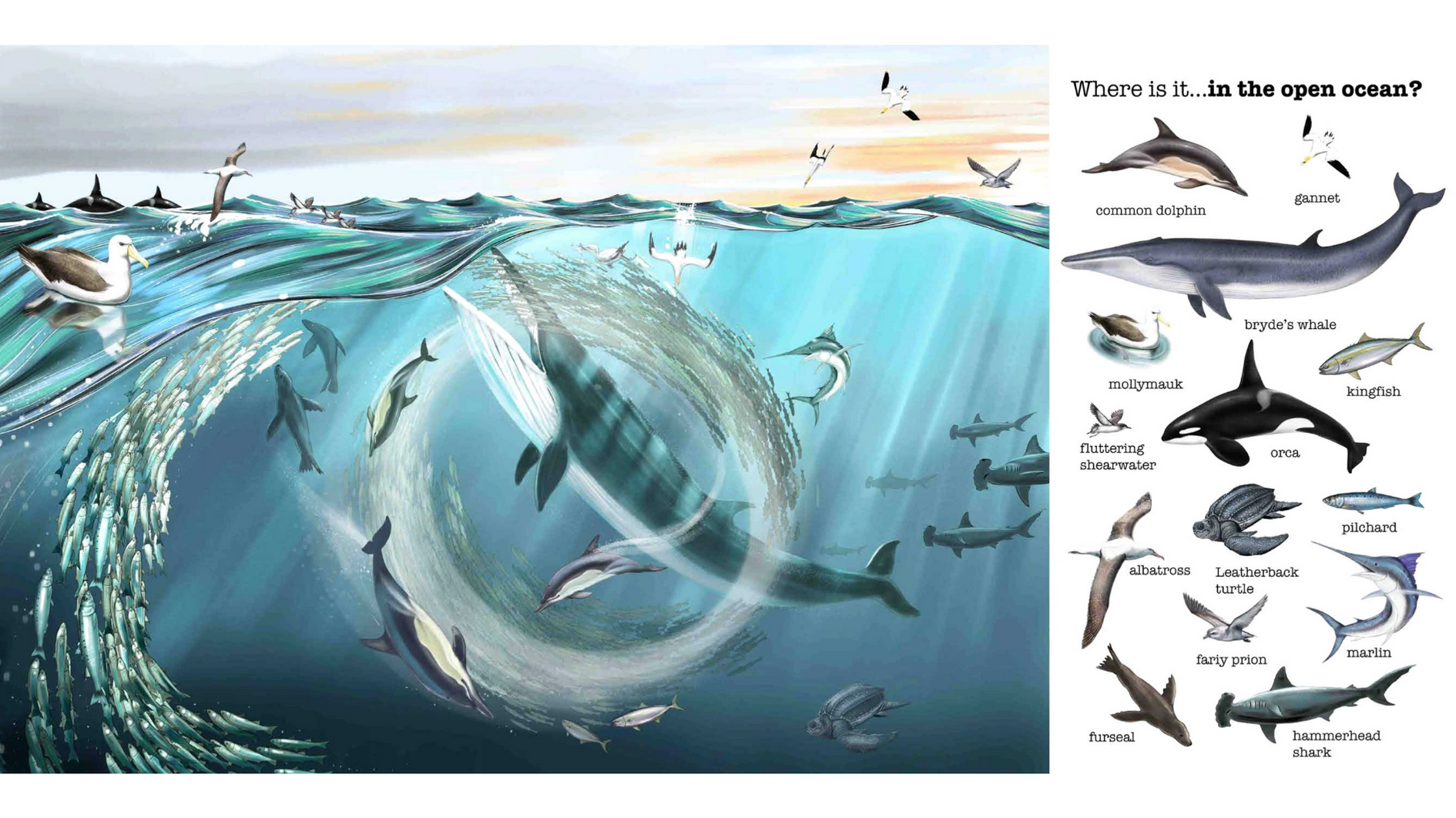

The second of Ned Barraud’s new books is an Aotearoa take on the classic ‘look and find’ concept. Where is it? A Wildlife Hunt for Kiwi Kids reminds me of summer afternoons spent poring over the pages of a Where’s Wally? book. This time though, instead of Wally, we’re searching for our country’s unique wildlife.

This book comprises eleven double-page spreads dedicated to different habitats you can find in Aotearoa— for example, wetlands, the deep sea, wildlife sanctuaries and even ancient forests to list just a few. The habitats take up three quarters of the double-page spread, and labelled illustrations of the different wildlife who live in them fill up the final quarter. Some are easy to spot at first glance while others require some careful seeking, but that’s what makes it fun. The interactive and engaging nature of the wildlife hunt makes it so readers don’t even realise the sheer amount of information they’re absorbing about Aotearoa’s natural world, especially since there isn’t any text to aid their learning, besides the names of the habitat and animals.

Ned uses the same natural colour palette in both What Happened to the Moa? and Where is it? A Wildlife Hunt for Kiwi Kids, but the illustrations in this book feel more satisfying to look at. I think this is because Ned wasn’t limited by only drawing one type of animal or environment here so the illustrations feel more vibrant and alive. I can almost hear the New Zealand sea lion roar and feel the icy mountain breeze nip at my nose.

There’s also a glossary at the end of this book that lists all the animals that made an appearance. They’re categorised by the environment you’d most commonly find them in, and each are followed with a few factual sentences about their lifecycle, diet, history and other areas of interest so that readers can expand further on the discoveries they made about Aotearoa’s natural world.

For the most part, both the English and Māori names for each animal are provided. However, in instances where there are animals that don’t have a Māori name, like lanternfish, then only the common English name is used and vice versa for those that only have a Māori name (e.g huia). My tip for a better reading experience would be to flip to the glossary each time you encounter a new animal in the book, because not only is it really overwhelming to read the glossary in one go, but it’s also difficult to retain fact after fact with no visual aid, especially since the language that is used requires a more developed vocabulary. It does help that, like in his previous work, the scientific terms like ‘endemic’, are all explained within the text. This makes it easier to understand the content without necessarily reaching for another resource.

The interactive and engaging nature of the wildlife hunt makes it so readers don’t even realise the sheer amount of information they’re absorbing about Aotearoa’s natural world.

Although it’s highly unlikely you’d encounter all the wildlife in their habitats if you went looking, that’s not the purpose of this book. This book is intended to teach children about the different habitats and the animals that live there, and it does just that— very well too, might I add!

Where is it? A Wildlife Hunt for Kiwi Kids

by Ned Barraud

Published by Potton & Burton

RRP $19.99

Nida Fiazi has worked in the New Zealand book industry for the past five years as a poet, editor, reviewer, and advocate for better representation in literature. She is a Hazara Kiwi Muslim and a former refugee based in Kirikiriroa. Her work has appeared in Issue 6 of Mayhem Literary Journal, the anthology Ko Aotearoa Tātou | We Are New Zealand, and Poetry NZ Yearbook 2021. She is currently penning an opera with Tracey Slaughter.