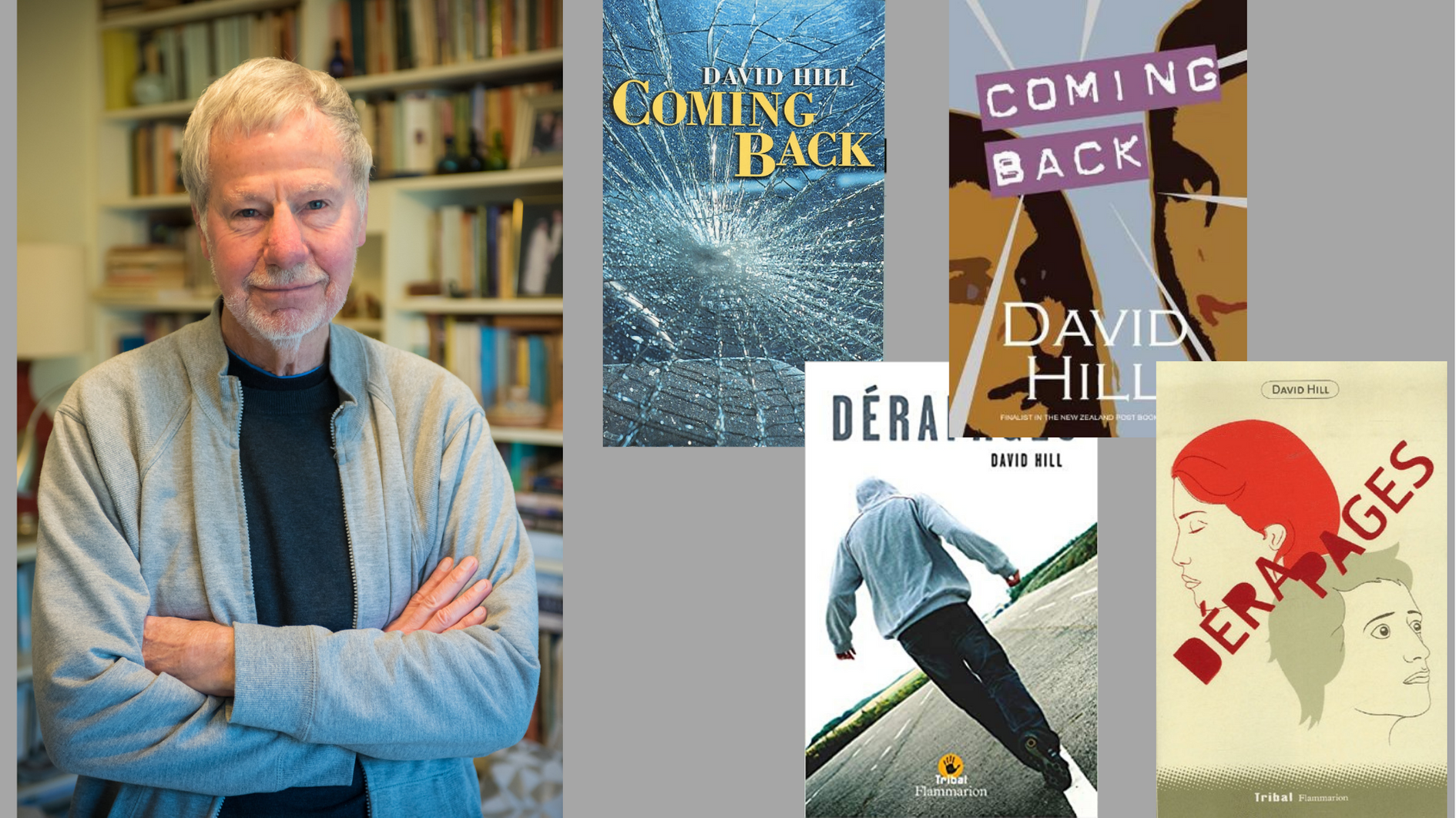

The death of the father of the family whose ordeal David Hill’s YA novel Coming Back is based on spurred him to think about how writers record and adjust reality to suit their narratives. Coming Back might not be regularly stocked by your local bookshop, but they can order it in for you to sink your teeth into.

Graham died a while back. A lovely guy, whose death came cruelly early. Nearly two decades before, I’d got to know him and his brave family while I put them in a book: Coming Back.

I put Graham in almost unchanged. That’s fairly unusual for authors, I suggest. Far more often, we change appearances, actions, mannerisms, rearrange the complexities of a real-life person so they fit our narratives more tidily. But Graham went in pretty much as he was.

He and wife Colleen’s teenage daughter Michelle had been grievously hurt when a car hit her as she crossed a road near their home.

He and wife Colleen’s teenage daughter Michelle had been grievously hurt when a car hit her as she crossed a road near their home.

For a while, it seemed she might die. She spent weeks in intensive care, then in hospital, before she made her slow, gallant return to school and life.

My wife Beth had taught Michelle, and told me about her ordeal, plus the courage with which she, her parents, and her older sister Brooke were facing it. Gradually, the realisation grew that I wanted to write about it—that blend of excitement and trepidation you feel when a story presents itself to you.

I went to see the family. I wanted to get their narratives, of course: the details they might think incidental, but which I hoped would give the plot focus and authenticity.

I went to see the family. I wanted to get their narratives, of course: the details they might think incidental, but which I hoped would give the plot focus and authenticity.

I wanted to see them for another reason, as well. I knew how arrogant and inappropriate it would be to try writing their story without their permission.

They were obliging and gracious, then and during the months following, as the book slowly took shape. They provided the specifics, the glints of verisimilitude to make a reader feel “this convinces; this sounds real”.

There were the sounds Michelle heard as she lay half-conscious; the strange telescoping and condensing of time; the comfort from medical staff and the acute discomfort of waiting room chairs.

The first draft was almost finished when Colleen suddenly told me how, as their daughter began coming out of her coma, she grew distressed, started thrashing around and crying out. The hospital felt they’d have to restrain her, tie her down in bed in case she damaged herself.

The first draft was almost finished when Colleen suddenly told me how, as their daughter began coming out of her coma, she grew distressed, started thrashing around and crying out.

Her parents weren’t having that. Colleen, a registered nurse herself, had heard of a treatment used in Scotland to help patients in the same plight as her daughter. So with the hospital’s permission, she placed mattresses on the floor; slept beside Michelle, holding and comforting her till her till the teenager became easier.

I rushed home, grabbed the chapter, inserted Colleen’s story exactly as she’d told me. (I thought it was exact, anyway; later I learned I’d managed to invent a few details.) I felt then and on numerous other occasions that I’d been given something precious; something I had to carry and use respectfully, almost reverently.

Sometimes I was given a salutary slap as well. In real life, the car driver was an adult. For the book, I turned him into a teenager. As I worked on the first draft, I wondered about a possible relationship starting between him and the girl he’d accidentally hit. When I mentioned it to Michelle, her reaction was…..emphatic. “Oh, yuk!” She was right, in terms both of probability and sensitivity.

Then there was the scene where the young driver makes himself visit the girl in hospital; face up to her. He comes away feeling he’s redeemed himself a fraction. I left the chapter with the family to read.

Then there was the scene where the young driver makes himself visit the girl in hospital; face up to her.

When I got it back, Graham had written “Big Hero???” beside the boy’s self-congratulations. He was absolutely right, too – and it made me realise again what liberties we take with others when we use them in fiction.

I’d begun by using the family the way authors use any source. I’d grown to admire and like them. I knew they were becoming wrapped up in the story: its fictional as well as factual elements. Michelle asked me shyly one time about a rather hunky guy who was a friend of the driver. “Is he someone who lives around here?” I wanted to hug her. Alas, the hunk was totally fictitious.

I fretted more than usual about the book as I wrote, revised, revised again, then finally submitted it. It had become the family’s story. I’d tried to warn them how chancy the whole business of getting something published is, but I knew they were looking forward to seeing it in print. I knew also that if it were rejected, I’d feel I’d let them down.

I fretted more than usual about the book… It had become the family’s story.

The title was Coming Back, because Michelle had indeed come back from the edge of death. It did reasonably well; was published in a few places overseas. I took a copy of the foreign editions to the family, and we all agreed that our Slovenian wasn’t that flash.

David Malouf has this lovely bit in one of his stories, as his writer protagonist (how many of us have used that trope?) begins work, and “slowly, his characters lift their faces up to him”. Every time I open Coming Back, it’s the faces of that gallant, loving family I see.

We write our stories; then we inevitably move on. Our characters start to recede, like neighbours who’ve shifted to another town.

We write our stories; then we inevitably move on. Our characters start to recede, like neighbours who’ve shifted to another town.

I saw members of the family intermittently over subsequent years. You tend to run into people in a town our size. I heard how Michelle continued to heal; how Colleen and Graham kept watching her with joy and the inevitable flicker of fear.

I was jolted when I heard Graham had died; it felt so unjust after all they’d endured; felt also that I’d lost someone who’d nearly become a friend.

We take from other people when we write. It’s part of the job. Most times, they’re unaware. But every so often, it becomes a sharing, a communion almost, with growth and deepening on both sides.

We take from other people when we write. It’s part of the job… every so often, it becomes a sharing, a communion almost…

It was like that with Graham, Michelle, and the others. It was a honour to work with them. My thanks to them all.

David Hill

David Hill is a prolific and highly regarded New Zealand writer, playwright, poet, columnist and critic. Best known for his highly popular and award-winning body of work for young people, ranging from picture books to teenage fiction, his novels have been published all around the world and translated into several languages, and his short stories and plays for young people have been broadcast here and overseas. He reviews books on Radio NZ, and across a wide range of print media.