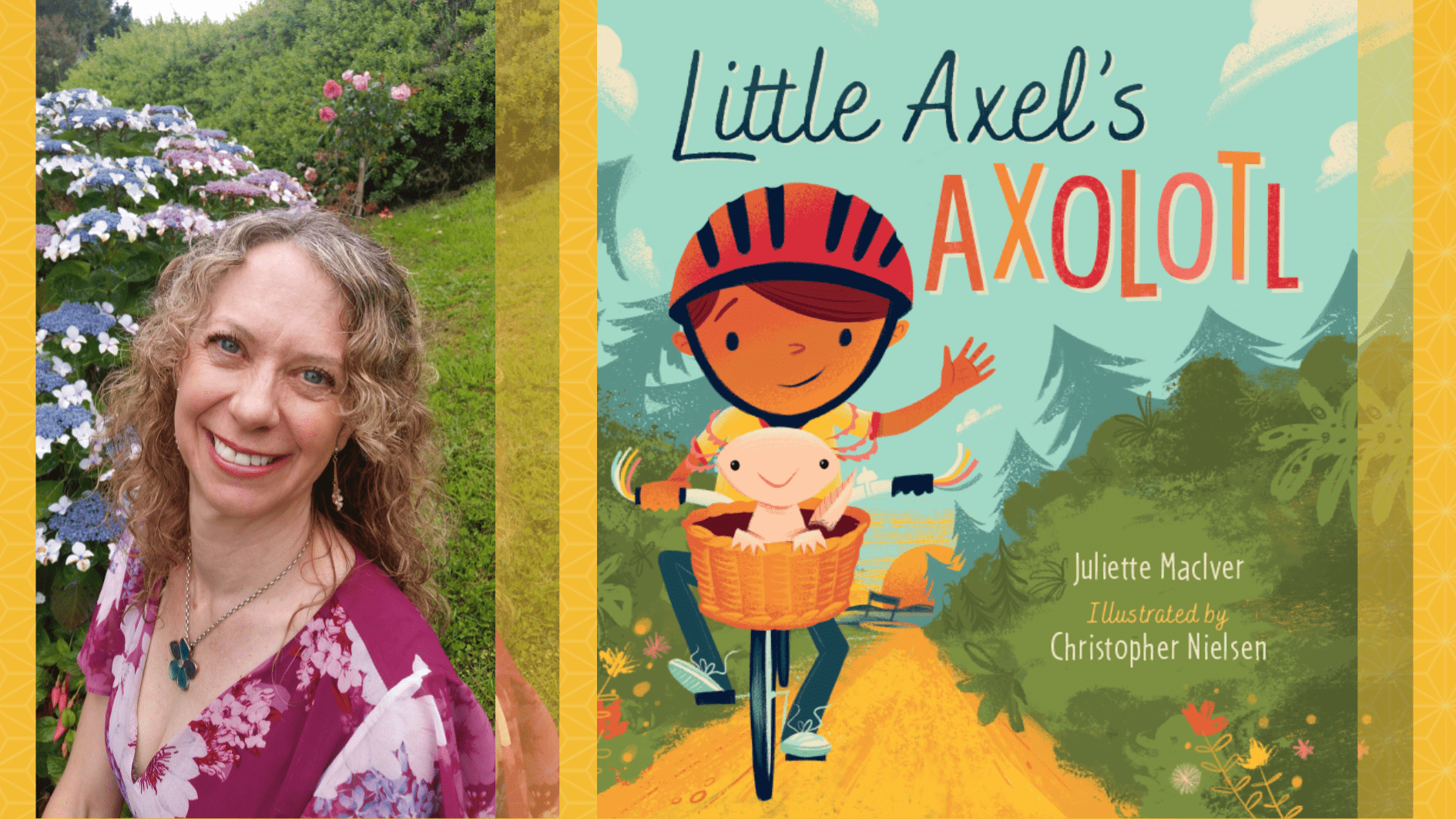

Effervescent wordsmith Juliette MacIver has just released her new picture book, Little Axel’s Axolotl, a whimsical story about a very loved axolotl that dreams of adventure. In classic MacIver style, it is full of brilliant soundplay and interesting vocabulary, and further cements her position as one of Aotearoa’s top writers of rhyming verse. Here, she chats with Annelies Judson about her writing (and reading) history, creating for the market, and more.

After I interviewed her for this piece, I decided to let AI do the hard work of transcribing our words. During the interview, MacIver told me that there was a period of time where she made everyone who came into her house say a set of words to see what vowel sound they used for each one. This seems very on brand for MacIver, who has a Master’s Degree in Linguistics and a delightfully meticulous approach to the craft of writing. I can only hope that the information she gleaned from her research is passed on to Google’s transcription AI bots, because not only was the transcript a “structural miss” (structural mess) but there were also places where there was a “mess of jump” (massive jump) between the different sections of the interview, and for a while I was worried that it “wouldn’t be with anything” (wouldn’t be worth anything) due to the way the AI had rendered our Kiwi accents.

However, the transcription AI came through in the end, when it took MacIver’s discussion of the linguistic phenomenon of “rhotic Rs” and beautifully rendered it as “aerotic ass”. It seemed an appropriate error for an interview that really highlighted the combination of humour and language nerdery that MacIver brings to her writing.

Annelies Judson (AJ): You started writing when your children were young, so I presume you were reading children’s books all the livelong day. Do you now have to make a super effort to go to the library to get out picture books?

Juliette MacIver (JM): Yeah, it really isn’t the same as having that built into your day as part of your duty in raising a child. There have been periods when I’m reading so few picture books. But recently I’ve started going to the library every Thursday with my two youngest kids: they find whatever they want, and I just go through all the picture books.

AJ: Do you focus on New Zealand picture books or are you interested in what’s going on with world trends?

JM: I have this programme for myself which essentially entails reading everything from New Zealand’s kids’ lit, and the best from the rest of the world. That’s kind of my general approach.

AJ: Who is your dream critique group?

JM: That’s tricky. I would have JK Rowling. I’d let Philip Pullman come along. I guess CS Lewis could pop in.

AJ: Obviously, so much of what you do is very based around wordplay. Are there people that you look to for those kinds of skills?

JM: I don’t know, I love Margaret Mahy, especially Bubble Trouble. And Dr Seuss was spectacularly brilliant. But they’re the most obvious ones to choose.

AJ: Do you think you’re quite a critical reader?

JM: Increasingly so in the last few years. I love critiquing and analysing stories. I should probably start writing reviews. I have a lot of discussions with my friend Ruth Paul, who’s a picture book writer and illustrator. She has just written a junior fiction story which she eventually agreed to let me read so I could give feedback. But initially she was like, “You’re a fierce and passionate critic and I don’t know if I want to be on the end of that.”

AJ: You studied linguistics at university. How much has that led into the fascination you have with words and sounds?

JM: I am absolutely fascinated with linguistics—and with language in general, in all its facets. I did my bachelor’s degree in linguistics in the early 90s. I just finished a Masters in Linguistics last year, which I did over a three-year period part-time. I loved phonetics in particular because it’s a really minute analysis of how phonemes work, and rhythm and intonation and all aspects of prosody, which is what I love about writing in rhyme.

I love playing with sounds. And also trying to account for all the variance that exists between different individual readers, like the way one reader might emphasise a different word in a sentence. But also trying to account for different accents. I’m trying to write verse that works for the New Zealand accent and the Australian and British, and American too. Sometimes that’s not possible and I have to just rewrite lines for American editions, but I do try to bear in mind all the different possible pronunciations in terms of vowel sounds and emphasis.

AJ: And that changes over time too.

JM: I find that fascinating too: how attitudes towards language change, and the extreme responses people have to change, which they seem to think poses some kind of threat.

AJ: I find that the people who are the worst at it are the ones who hark back to writers of eras gone past and say, “But shouldn’t we all be looking to Shakespeare or to Milton?” When, if you look at Shakespeare or Milton, actually you’d find out the language has changed significantly since then and maybe we shouldn’t be quite so snarky.

JM: Exactly. Milton’s parents would have been disgusted with the language he used. And his grandparents even more so.

AJ: Do you have a favourite line in any of your books?

JM: ‘The llama made marmalade’ has always been a pleasing line [from Marmaduke Duck and the Marmalade Jam]. Because I love the spoonerism as well as the rhythm, and it resolves the plot of the story in one fell, spoonerising swoop.

AJ: I’ve heard my eight-year-old say “Great Scott!” about four or five times in the last few days. I’m positive he got that from Duck Goes Meow.

JM: That’s great! It does make me sound terribly wholesome. Though in my Faelan the Wolf series I did write “for fox’s sake!” as one of the things that the wolves say when they’re angry. I was worried the publisher wouldn’t let me use that. But Scholastic really loved it. And then in the teacher notes that go along with the books, I noticed that it said the author uses alliteration to add emphasis. And what was the example? “For fox’s sake!” And I thought, the character says “for fox’s sake!” because of the phonetic proximity to another expression that we tend to use when we’re angry. Nothing to do with alliteration. Perhaps best not to draw attention to that particular line in class [laughs]. That was hilarious.

AJ: What was your writing history before Marmaduke Duck [MacIver’s first book]?

JM: I wrote a lot of stories as soon as I could write. I wrote long stories all the time. Mostly they were meandering and ridiculous. I had no idea about story structure until well into my thirties. On my school reports it mostly said things like, “Juliette writes too much. She needs to edit things.” I was not in the least bit interested in editing or in shortening anything I wrote. I just really loved writing.

On my school reports it mostly said things like, “Juliette writes too much. She needs to edit things.”

AJ: But you really focused on your writing in your thirties when you had your kids?

JM: Yeah. I was doing improv comedy at that stage and I happened to join a group that had a very story-based approach to improvised theatre. So that’s where I learned some basics about story structure that I just hadn’t grasped earlier. And that made all the difference. Before then I just wrote random pieces of verse. Once I understood a little bit more about story structure, I decided that one thing I wanted to do, on a long list of things, was to publish a children’s book. So I started writing. And I loved it. After a while it became my aim to become a published author so that I wouldn’t have to go back into the workforce. That was the main thing at that time. I wanted to do some work that you could do from home in those days.

AJ: I noticed when I went through your book list that there was a period of about five years where you didn’t publish anything…

JM: Yeah, I got nothing but rejections for five years solid. That got very disheartening. I got to the point where I was going into schools to say, “So, what’s it like to be an author? It sucks.” [laughs] I didn’t actually say that but it was becoming a bit of a facade. You’re telling kids, “You just have to persist,” and you want to say, “Sometimes you should give up, kids. Not enough people give you that message.” It was really frustrating and disheartening. And I just didn’t know why I wasn’t getting anything accepted.

AJ: Did you think about giving up?

JM: Not really. I’m quite unrealistic in some ways. I thought, “No, I’ll make this work”. Lots of self belief and a lack of realism can be quite a good combination. And also, I guess I write books to entertain myself. Even though I’m trying to write for a market, I’m really writing because I love writing. Then every time I have a book published I’m surprised by how much children like them.

AJ: You wouldn’t want to gut your own creative instincts just to meet the market.

JM: Well, there’s an interesting contention there. Before I wrote Duck Goes Meow [by MacIver and illustrator Carla Martell, which has sold well here and overseas], publishers had been telling me for a few years to write more simply. It seems that it is harder to sell more complicated, more wordy stories with richer vocabulary, generally speaking. I love writing in the elaborate style of Queen Alice’s Palaces and Henry Bob Bobbalich. That kind of language is what I enjoy most of all. And so I was just not interested in writing more simply. But to make it a viable career you really should listen to what publishers are asking for. Getting direction from your publishers is a very rare thing, I have found. So when they actually say to you, “We want this…”, then it’s a good idea to listen. That took me a long time to realise. A long while ago, I was asked to write some junior fiction thing. The publisher sent me a brief and I was like, “Meh, I don’t want to write that.” If that happened now, I would make it work. I would write it in a way that satisfies me, even if the idea didn’t appeal. I really have to concur with Lynette at Scholastic that writing simply was a good idea in terms of trying to make a living from this, because Duck Goes Meow has just gone off. It won the NZ Book Awards last year and it’s been translated into multiple languages already. They printed over 30 thousand copies in Belgium.

AJ: Interesting.

JM: I think it’s a balance of trying to write for the market and writing what you really want to write. But even when you’re trying to write for the market, one way to look at it is that it just sets parameters around what you’re doing, and that further refines your ability. You have to work within a tighter framework. But you can still bring the same principles to the work: story structure and strong characters and good rhyme and scansion and the kind of feel that you want for the story, all of that can be included within those parameters. It’s really a good challenge. You can still produce something good within market limitations, that’s what I’m saying. It is satisfying.

You can still produce something good within market limitations, [is]what I’m saying. It is satisfying.

AJ: You’re also writing books for older children now. [MacIver has written three books in the Faelan the Wolf series, aimed at eight- to 12-year-olds]. There must have been an interesting process to go from picture books to that longer form.

JM: Actually I started writing Faelan as a picture book. And it just got a bit too long. Picture books shouldn’t be more than a thousand words, but at its longest incarnation Faelan was 80,000 words, so it was a bit long for a picture book [laughs]. And it was a structural mess that took years to fix up. I learned an awful lot from that.

AJ: Is there an idea that you’ve wanted to turn into a book that you haven’t been able to for whatever reason? Something that keeps niggling away at you?

JM: I feel like I’m very loose with my ideas for picture books. I have a lot of ideas all the time and I just let them go because I can’t be bothered writing them down. If I really want to write it, I just expect it to stay. If it’s that good, if I’m really gripped by it, then I write it.

Also, I’ve always wanted to write an adult novel, but I don’t know what about. Part of the barrier is that it’s an enormous amount of work for virtually no money.

AJ: What’s your five year plan?

JM: I’m very focused on this new junior fiction series I’m writing, which is for 10 to 14-year-olds and will be seven books long. It’s ridiculously ambitious. Every now and then my husband says, “Couldn’t you make it three books?” Sometimes I think he’s right. I mean three is far more realistic. I‘ve only written the first one. And then I rewrote it, and I’m going to rewrite it again. It’s such a slow process, involving draft after draft. But the reason I decided on seven was that I originally thought I’d write really simple stories for eight-year-olds and they’d be seven to ten thousand words each and then the whole seven books would be manageable. Then when I wrote the first book, everything blew out bigger and bigger. The first book is around 60,000 words now and the background document detailing the series is 80,000 words, so it’s all mushroomed enormously. But I’m very committed to this series and I really want to make it work.

* * *

Juliette MacIver’s newest book is Little Axel’s Axolotl, available now.

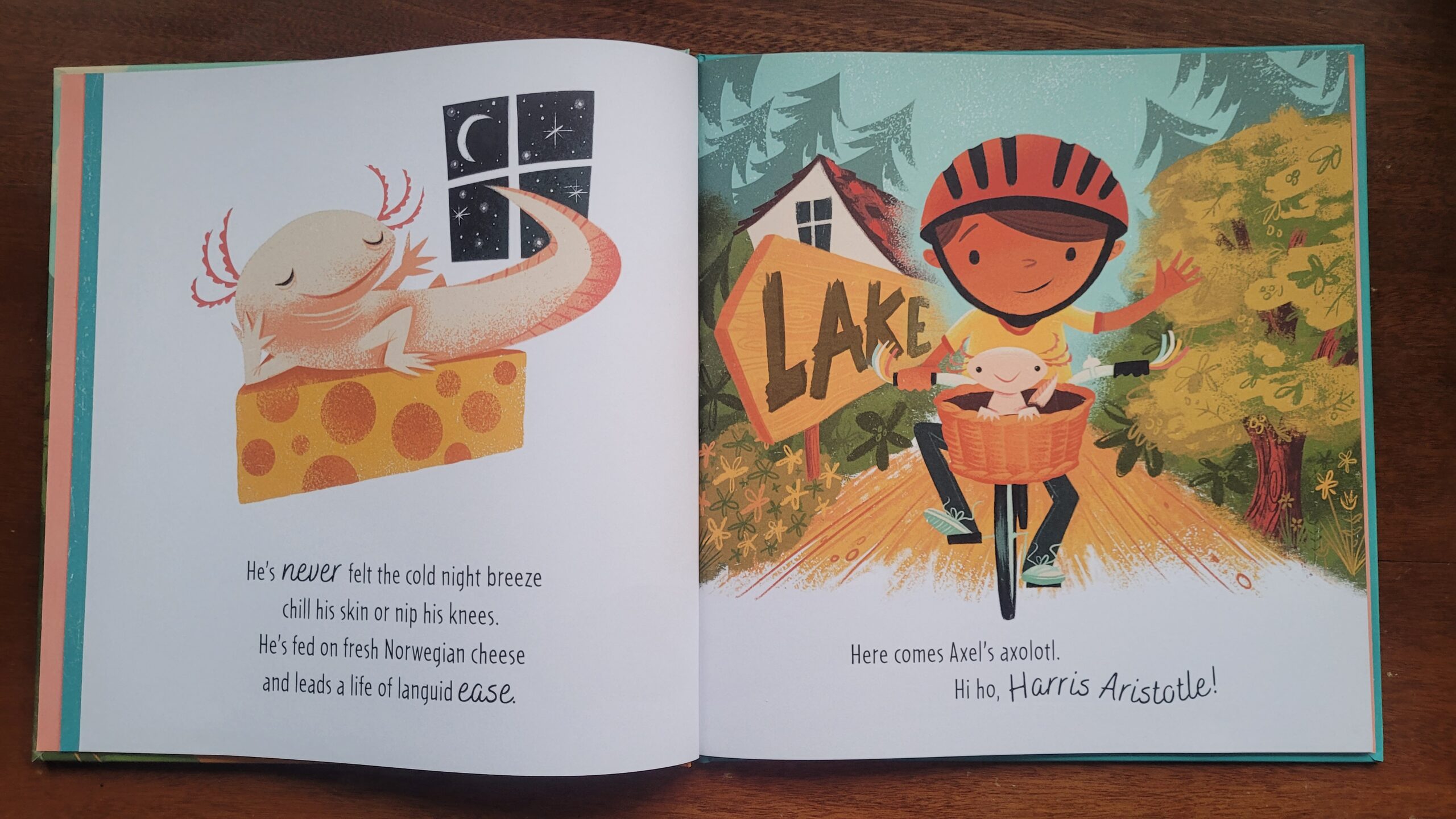

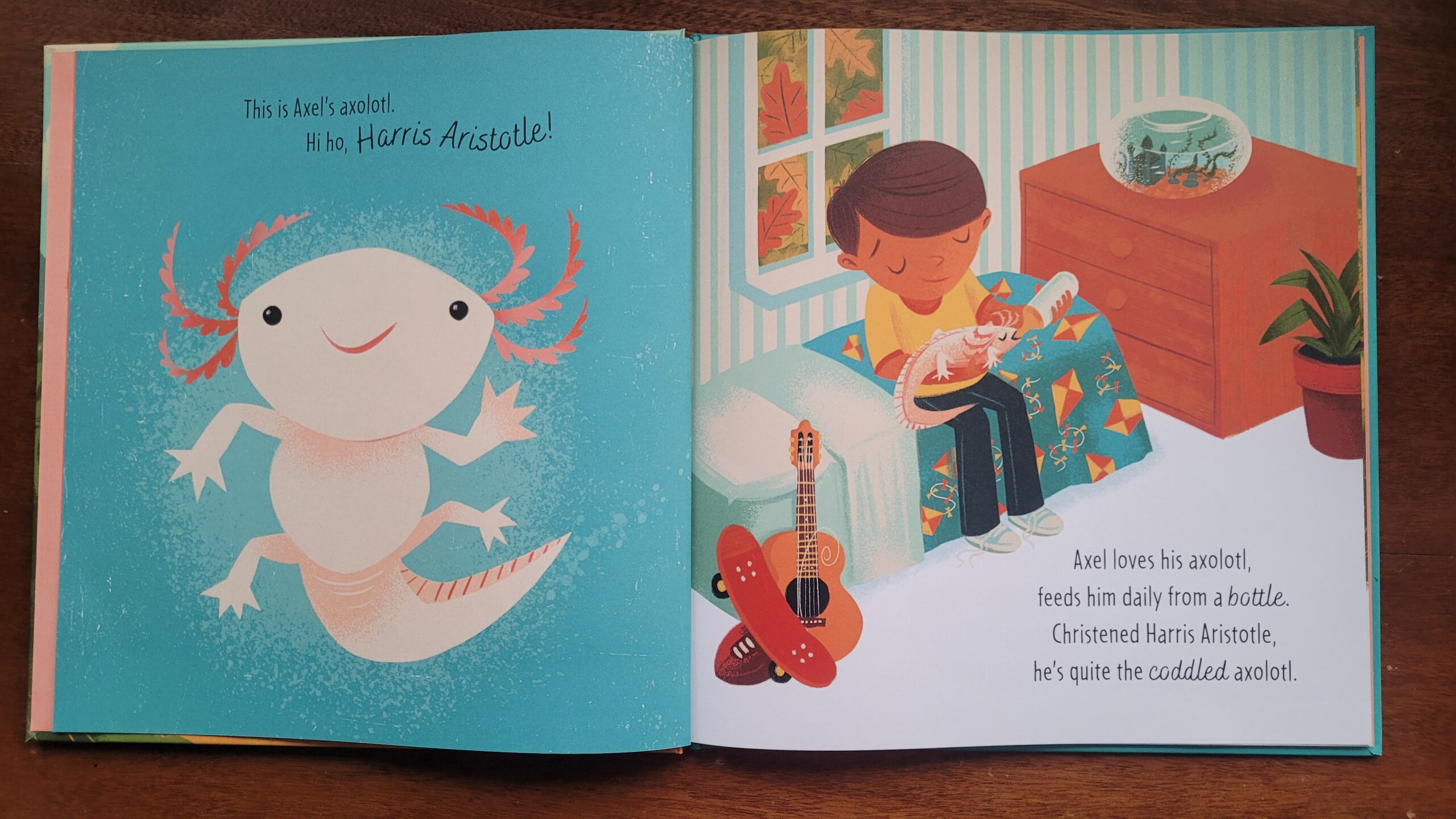

Little Axel’s Axolotl

By Juliette MacIver

Illustrated by Christopher Nielsen

Published by Walker Books Australia

RRP: $28.00

Annelies Judson

Annelies Judson writes book reviews and poetry for children, among other things. Her many loves include cooking, cricket, science and the em-dash. She can be found on Twitter/X and BlueSky @babybookdel and on Instagram @annelies_judson_writer. She also has a Substack newsletter starting February 2025, @anneliesjudsonwriter.