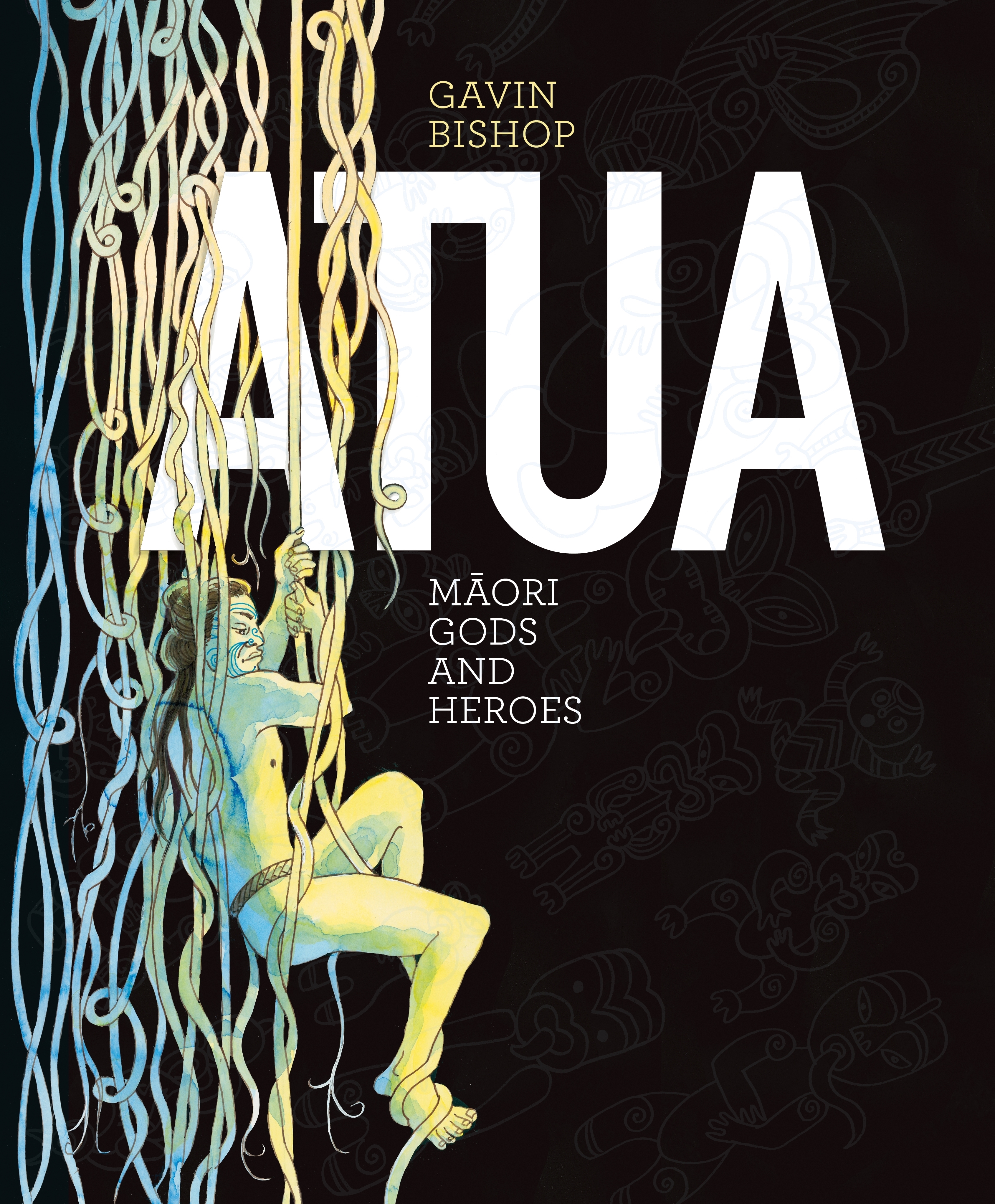

Gavin Bishop is an acclaimed author and illustrator of many beloved children’s books. Amongst his numerous accolades are the Prime Minister’s Award for Literary Achievement in 2019 and the 2018 Margaret Mahy Book of the Year Award for AOTEAROA. Whiti Hereaka—a fan-girl from way back—was pleased to kōrero with Gavin about his latest book, ATUA – Māori Gods and Heroes.

Whiti Hereaka: The size of Atua is impressive—I believe it is the same as your award-winning Aotearoa—and the first thing I thought was: yeah, the stories of our Atua are big stories and so a book that contains them ought to be big too!

Gavin Bishop: Atua is a similar size to Aotearoa but a slightly different shape. I did not want it to be seen as part three after Aotearoa and Wildlife of Aotearoa. I wanted it to stand alone.

It is an illustrator’s dream to be given such a big canvas to work on. The catch was of course, I also had to research and write the text and find room for it on the pages where I wanted my pictures to dominate. The size of the book, it’s length and page size certainly influenced the way I retold and illustrated the pūrākau.

I loved how the book incorporates tikanga Māori from the very start – we open the book in Te Kore we move through Te Pō and Rangi and Papa and then to your mihimihi — it felt very much like you were opening the space for me as a reader.

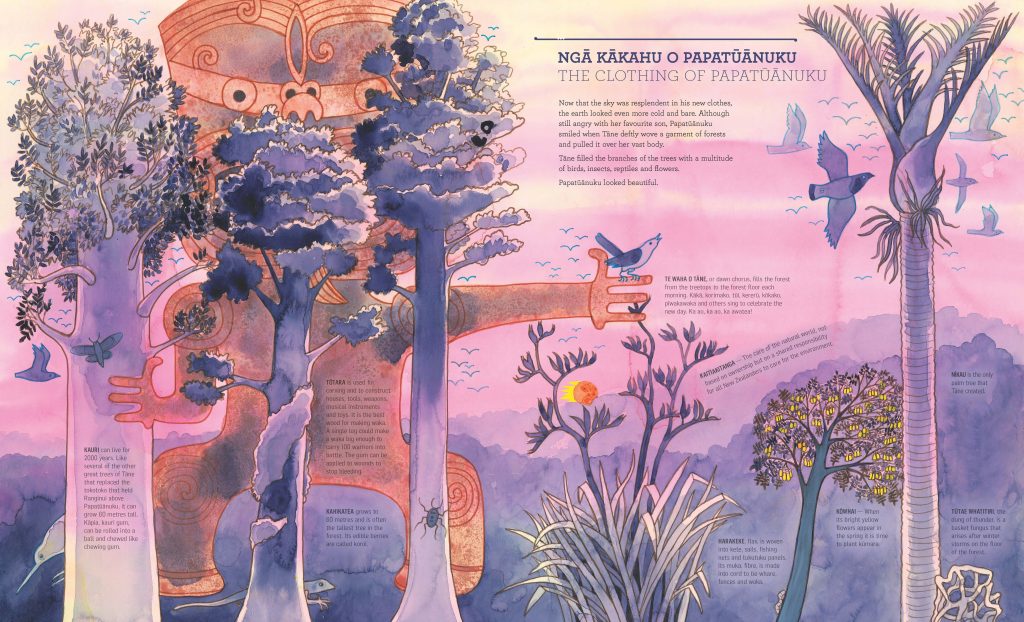

I wanted to make clear from the beginning that these stories were from this part of the world. I wanted to show how they have been told with mātauranga Māori for centuries in this country. I realise they have undergone huge modifications since they were brought to our islands by early Polynesian settlers but they have been retold here for so long that we think of them as pūrākau Māori.

I wanted to show how they have been told with mātauranga Māori for centuries in this country.

Throughout the whole of this book I tried to allow tikanga lead the way, show why and how things happened and how the characters in the stories were affected. After all, like all creation stories, Greek, Christian, Navajo and so on they were told to help explain the natural and spiritual world.

I really believe that telling and listening to pūrākau help us to understand who we are. So, I thought it was marvellous that you’ve suggested that Māui might have had ADHD in his story. How did you make this connection?

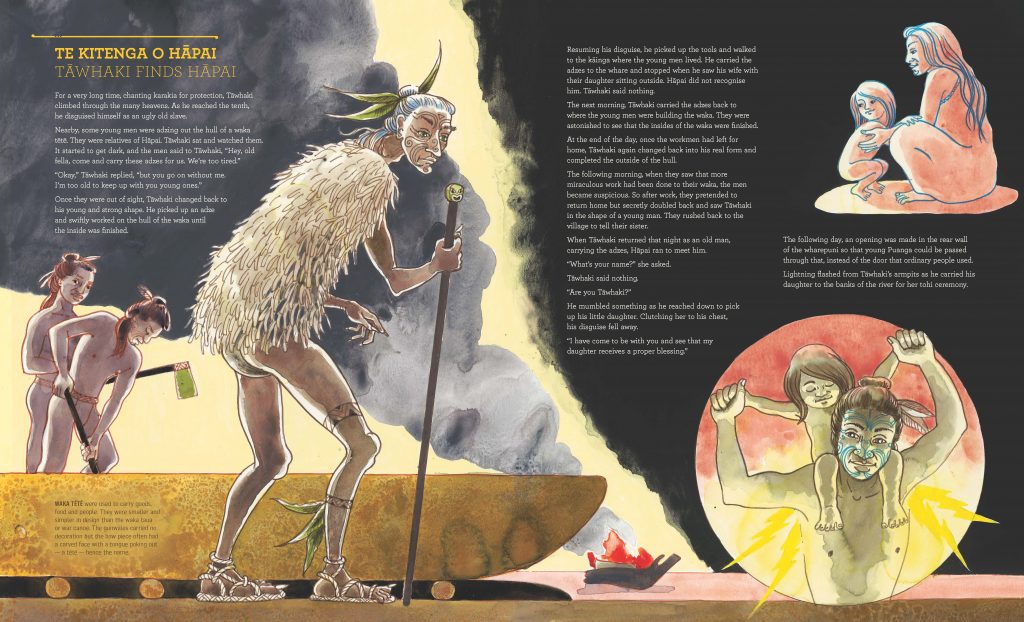

Several people in my family have ADHD in one form or another and it seems to me that Māui has a lot of similar traits to them. He was quick, clever, active, cunning and inventive but, unlike my whanaunga, he could also change his shape. I think that Māui is a wonderful character, a wonderful invention. He is small, the ‘runt of the litter’ but he always comes out on top, until of course he took on Hine nui te Pō.

[Māui] was quick, clever, active, cunning and inventive but, unlike my whanaunga, he could also change his shape.

He relates to, and is friends with small creatures—lizards, frogs, rats, and tiny birds like pīwaiwaka. He is very similar to Raven in North American Northwest Coast mythology. They are both trickster characters and many of their stories involve poorly thought through behaviour that causes problems for those around them. A Māui story that exemplifies this is, is when he turned his sister’s brother into a dog, the first dog. When Māui is outwitted by Hinenui te Pō he brings death into the world.

I suppose I was being a bit cheeky to suggest that Māui may have had ADHD but that’s what story tellers do, have always done—shape the retelling of the story to suit their audience.

Atua spans from Te Kore to the great migration, are you planning on continuing the story?

There are hundreds of tribal stories and histories that could not be included in my book because of a limited number of pages. The descendants of the the various migratory waka all have their stories. There are a lot of wonderful local stories too, such as the one about the beached whale at Sumner in Christchurch or the stories of the rainbow god who lived at Te Tihi o Kahukura at the top of Cashmere hills, where I live. Our country is clothed in stories, old and new, Māori and Pākēha.

Currently I am working on two books, a babies’ book in te reo as a follow-up to Mihi and Koro published by Gecko Press, as well as a colouring-in book for Penguin Random House. The former will be an introduction to te reo for little kids and the latter, designed for everyone, will come in handy during future lockdowns. I loved colouring books when I was a kid and some of my fondest childhood memories are the times I stayed with my grandmother in Invercargill and we walked into town to buy a new colouring book from Woolworths.

Some of my fondest childhood memories are the times I stayed with my grandmother in Invercargill and we walked into town to buy a new colouring book from Woolworths.

For me as a reader the “end” of your book feels like where my personal story starts — I can go on to follow Te Arawa and Tainui, is that what you’d like readers to do?

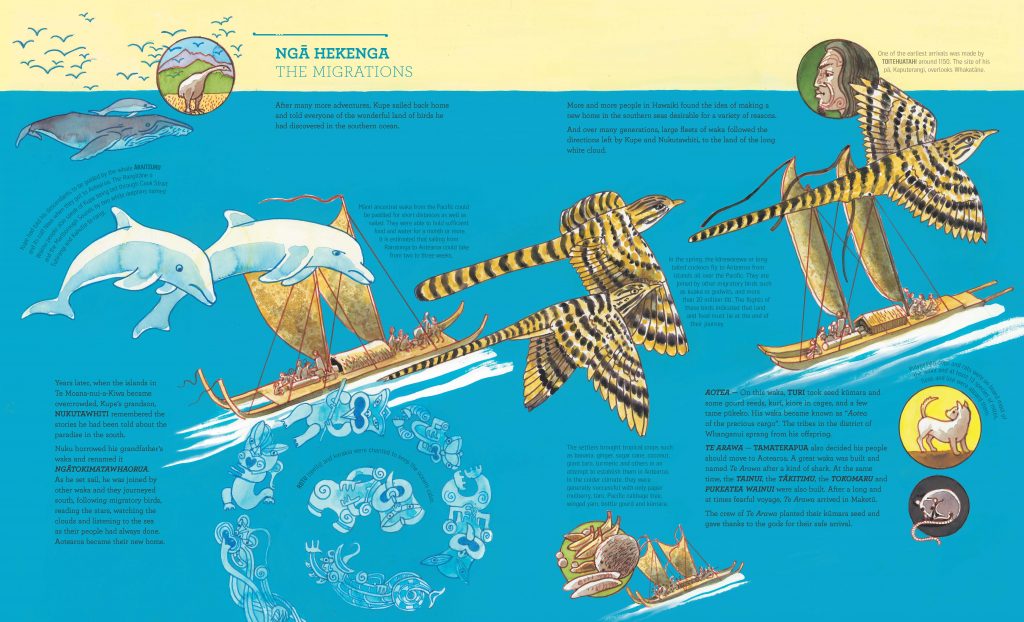

That’s right. As I mentioned previously, these stories were already very old when they arrived here in the heads and hearts of the first Polynesian settlers. The great migrations are an important part of the story of this country. When I was at primary school in the 1950s we were told a lot of rubbish about the so-called arrival of the Māori.

The great migrations are an important part of the story of this country.

The fact that they weren’t called Māori when the settlers arrived from Polynesian 800 years ago was never mentioned. Our teachers told us that seven waka, called ‘canoes’ in those days, arrived after perilous out-of-control journeys. Good luck swept the canoes here with the help of storms and other acts of good fortune. Extraordinary navigation and sophisticated nautical skill had nothing to do with it, we were told.

Captain James Cook in 1769 had commented in his journals how impressed he had been by the navigational skills of the Hawaiians and Tongans, but no-one teaching children in New Zealand in 1950 seemed to remember that. This has changed and I hope that my book along with many others, will help to remind the world that probably hundreds of waka over many generations travelled here from islands to the North. I was unable to mention them all, so I hope I will be forgiven for naming only a few. I hope I will also be forgiven for mentioning my ancestral waka, the Mataatua and Tainui — another storyteller’s privilege.

Whiti Hereaka

Whiti Hereaka is a writer of Ngāti Tūwharetoa, Te Arawa, Ngāti Whakaue, Tuhourangi, Ngāti Tumatawera, Tainui and Pākehā descent, based in Wellington. She is the author of The Graphologist’s Apprentice, and the award-winning YA novels Bugsand Legacy.Whiti’s latest novel for adults, Kurangaituku, retells the story of Hatupatu, from the ogress bird woman’s point of view.