Katherine Hurst chats with Sarah Wilkins about her new book, Diary of a Marine Biologist, scientific curiosity, AI and sea anemones.

Katherine Hurst: Can you tell me a little about your background? How did you get into illustrating?

Sarah Wilkins: I chose illustration as a career when I was 16. Even though I had no idea what an illustrator actually did, I gathered it was a freelance life and that I’d be able to travel the world. That suited me fine as I had itchy feet. After high school I studied Visual Communication Design in Wellington, then, as soon as I graduated, I left New Zealand for the bigger publishing pastures of Australia. From there I set my sights on the even bigger world of advertising and editorial illustration in Paris and New York. Two decades later I found myself back in Wellington with a young family and a burgeoning picture book career.

More recently you were at Victoria University studying a Master of Science in Society. What did this involve, and how did it impact the way you illustrate scientific concepts?

It was a massive change from being a freelance illustrator to being a full time student. It basically involved absconding from family life for a year. I quickly discovered that scientists love to discuss the black and white, the yes and no, whereas artists enjoy engaging with the blurry middle ground. Fascinating terrain for discussions.

… children’s books hold huge potential to foster a lifetime of scientific curiosity and engagement

As part of my research I looked at the visual communication of science in society in relation to editorial illustration and children’s publishing. Linking science to literacy is a wonderful way of integrating science into everyday life for children. Sometimes children’s literature adopts a deficit model, which I have reservations about. Books work best when the child characters participate in the science rather than being the passive ‘empty vessel’ ready to receive the knowledge from the grown up ‘expert’. The young reader loves to see themselves in the story, and to see science as part of their everyday life.

I think that children’s books hold huge potential to foster a lifetime of scientific curiosity and engagement—so getting it right matters.

When illustrating a scientific concept, how much research do you find yourself doing? And do different audiences affect this?

It all begins with research. I love it! I love becoming an amateur specialist on any number of topics depending on my work schedule. It’s often only an impending deadline that pulls me out of the rabbit hole of research and onto the pages of my sketch book. Whether it’s illustrating an article for New Scientist on microplastics or a picture book for 3 year olds about the making of the moon, it’s the most intense phase of a new science assignment.

Do you think of yourself as an illustrator who has a science focus, or is science just one of the many areas you have an interest in?

Probably the latter. Recently I’ve been lucky to be offered some incredible science related projects. Each book I illustrate is like a stepping stone to the next book, so it slowly builds to being a bit of a specialty. But there are so many things I’m interested in that I would love to combine with illustration.

How did you come to be working on Diary of a Marine Biologist with Anita Thomas?

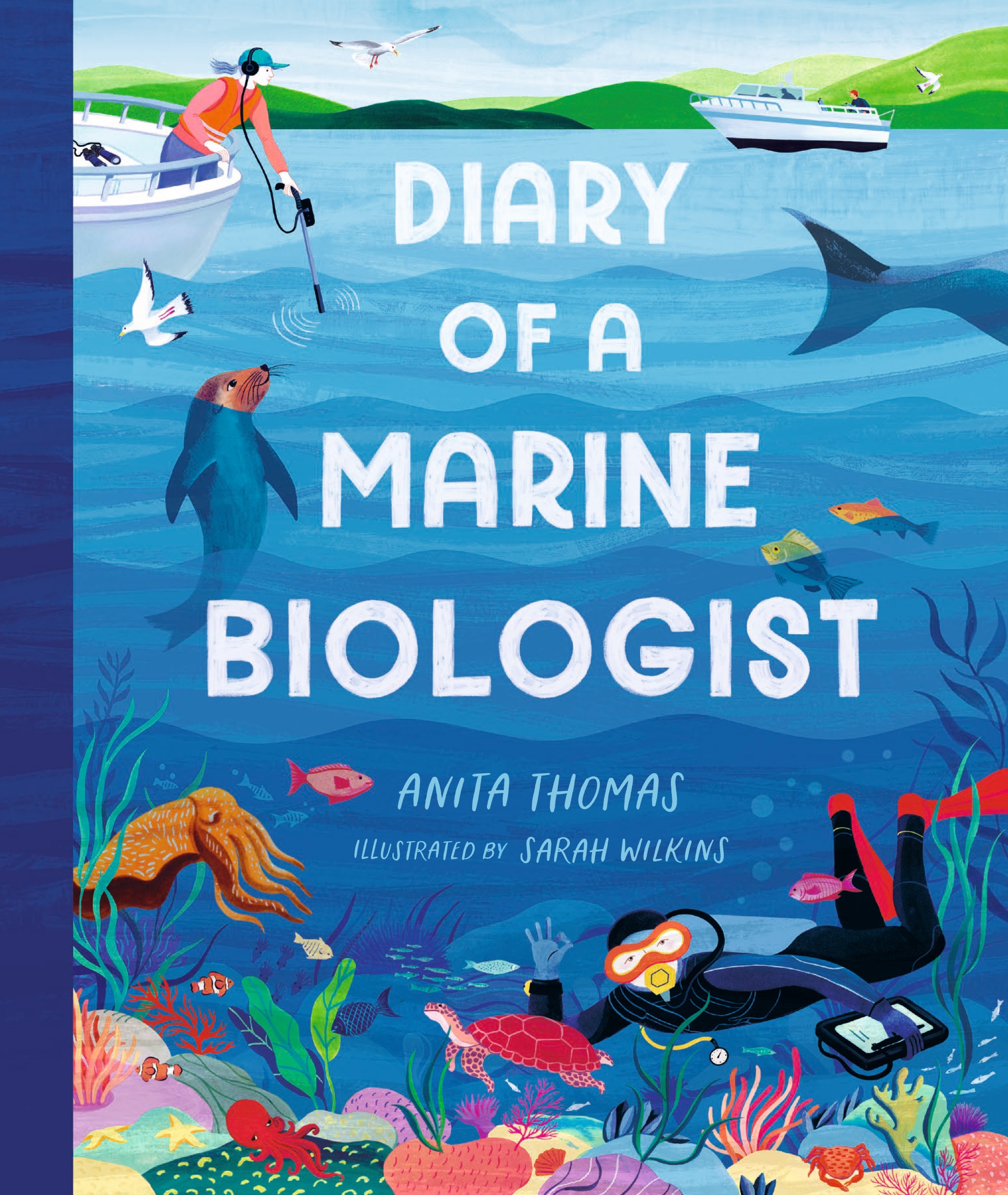

Clare Halifax from Walker Books asked if I was interested in illustrating the book way back in 2022. She told me about Anita’s work as a marine biologist in Australia and I really didn’t need any more convincing. I accepted the project before even reading the manuscript.

Did you meet, how closely did you work together?

Anita and I were in touch through Instagram quite early on in the process. I could delve into Anita’s account for fantastic reference photos of her in action, her marine projects, and more recently her new baby pics.

Do you like fish?

I’m a massive fangirl of sea anemones. I have vivid memories of a primary school trip to Pukerua Bay when I discovered the mysterious universe of a tidal rock pool and became infatuated with sea anemones and their grippy squishy tentacles. Still am!

When you are illustrating a nonfiction book like this, how do you make sure the illustrations still feel like your own? It is difficult to keep all the details accurate, while still retaining your style?

Just like in science, it’s an iterative process. There’s a lot of frustrating trial and error with my technique, feedback from editors and slow improvement until I achieve the right blend of accuracy and artistic licence. And there’s also the challenge of maintaining continuity throughout an entire book. I would never be able to do the meticulous work of a scientific illustrator, but I love the challenge of working in nonfiction—depicting accurate details while staying true to my own visual language.

Diary of a Marine Biologist contains many facts, but also a strong storyline where we are introduced to Emma, the marine biologist, and she leads us through her work week. How do you make sure the illustrations for both the facts and the story work together?

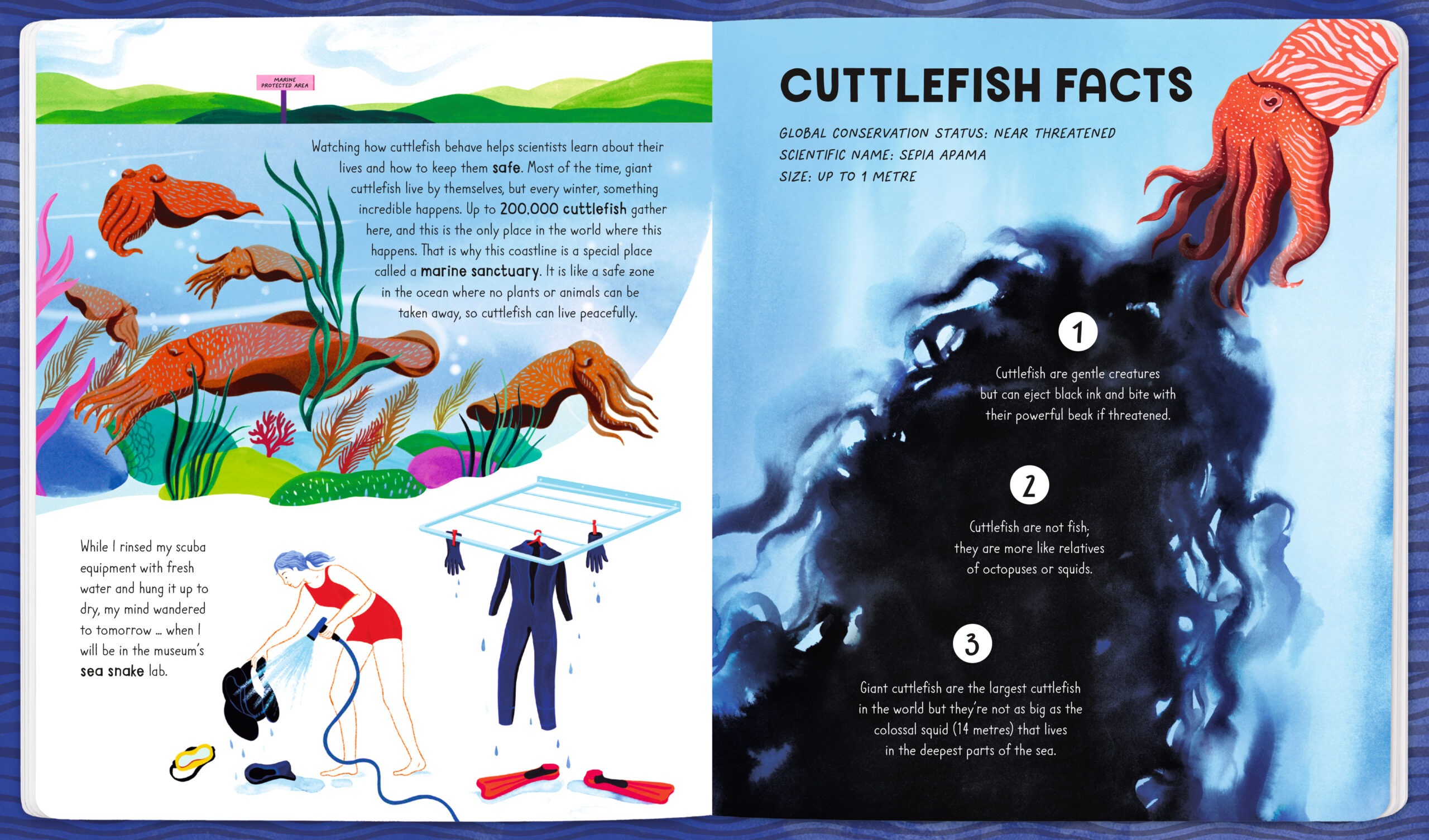

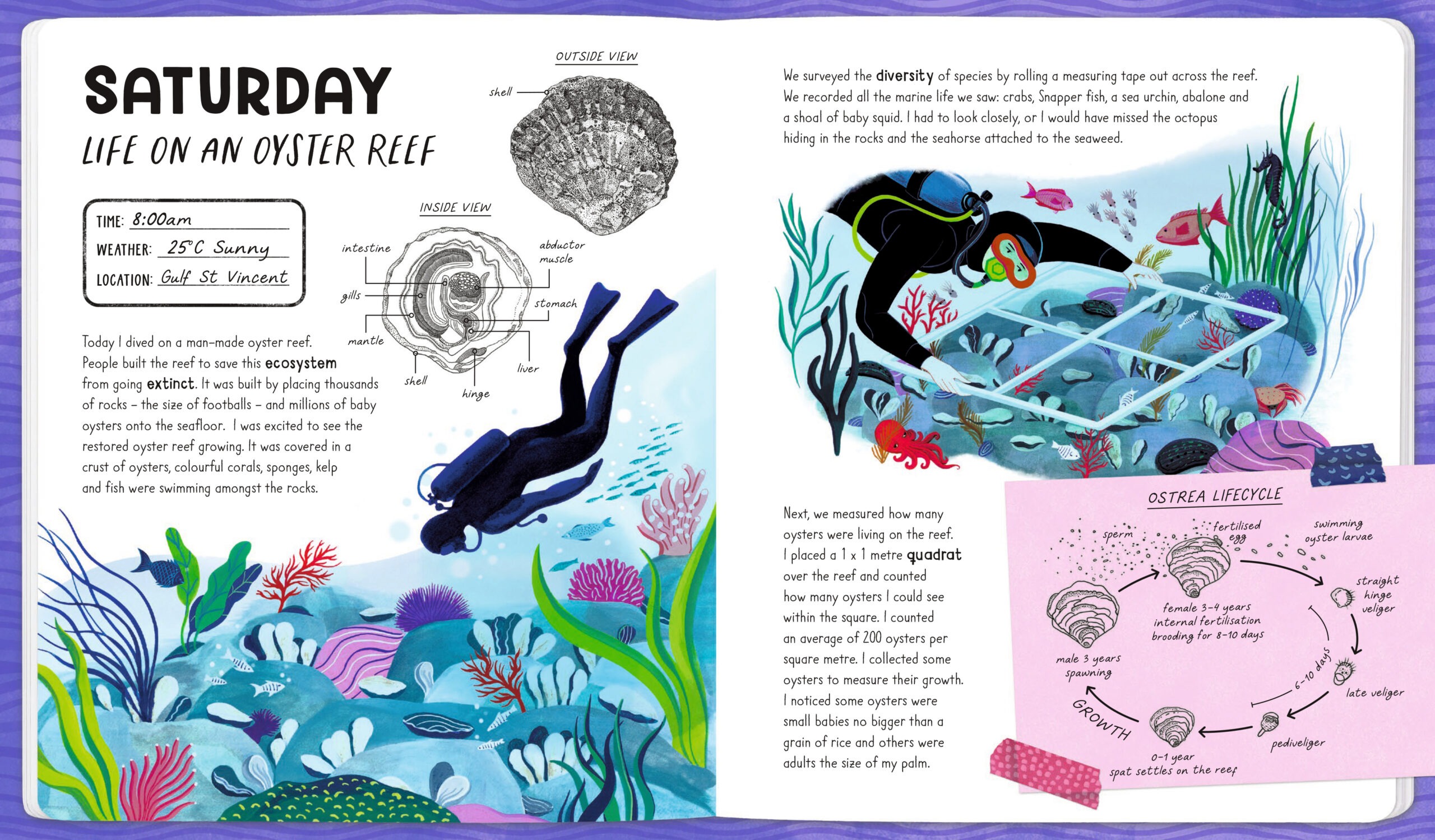

I tried not to distinguish between the two strands. Anita’s text cleverly sneaks in the science in the guise of an exciting week’s adventure. Likewise with the illustrations, I wanted to create cohesion between the facts and the personal story told by Emma. The wonder of narrative illustration is that it can help bridge the gap between science and children’s cognitive reasoning.

The main text is simple to understand, but some of the illustrations have a lot more jargon or more complex concepts. This means the story can be read by (or read aloud to) young children without getting bogged down in anything more complex, while older or more curious children can get more detail from the illustrations. Is it difficult to get this balance right?

I think the design of this book works brilliantly to achieve this balance. Anita’s black and white specimen drawings provide an interesting contrast to my painterly colour illustrations of Emma’s day to day experiences. The two contrasting styles were cleverly integrated into the diary format by the book designer Sarah Mitchell at Walker Books.

In one illustration, there is a map in the background while Emma is typing (thanks for including New Zealand on the map!)—do you have any pet peeves of scientific concepts or things in the natural world that are frequently illustrated incorrectly?

My pet peeve is when generic illustrations are plonked alongside specific text. A well commissioned, researched and executed illustration that is appropriate to the topic can do the hard work of a page of text. It’s a shame to waste that opportunity with ‘filler’ art.

Books work best when the child characters participate in the science …

When you’re collaborating with a scientist, do you ever feel intimidated because you know so much less about their specialist subject?

Always, but my curiosity and the need to understand their work in order to do my job overrides my intimidation pretty quickly.

You illustrated a book, Like the Ocean We Rise, which uses the idea of a raindrop to represent each person’s actions. It’s a great way to show the power of working together. When you are illustrating difficult or depressing topics, such as habitat destruction and climate change, how do you do that in a way that doesn’t make readers lose hope?

I do love a good visual metaphor. They’re brilliant tools when tackling tricky subjects. Despite the doom and gloom, Like the Ocean We Rise by Nicola Edwards is both a realistic and hopeful book about climate change. Yes, it’s possible! Research shows that children feel climate change and habitat destruction as emotional issues. They care about the planet, the oceans, the animals, the insects, their friends and family. If children see themselves in a book, the topic becomes more relatable and not some scary, far away problem. So, I simply placed children in the picture. I stepped away from realistic visualisations and towards integrating the facts into imaginative visual storytelling with familiar narratives. It’s all about helping the child understand the topic on their own terms.

Good books take time and are difficult to create …

Illustration software and AI make it quicker and easier for someone to produce images, but illustrating a book is much more than just a sequence of images. Have you seen anything changing as these tools become more available?

Anecdotally, I get the impression that the children’s publishing industry is becoming increasingly wary of AI. There’s so much murkiness around copyright and AI training which means that risk averse publishers are tending to look a bit more closely at that side of things. I’ve also noticed publishers are beginning to include information on the imprint pages about the illustrations. For example in Diary of a Marine Biologist you can read that my illustrations were created by hand using gouache and inks. Good books take time and are difficult to create—that’s a fact. If we increasingly outsource our creative tools and processes to AI, the much-hailed gains in speed and ease will inevitably make our jobs redundant.

Have you ever produced a book entirely by yourself, with or without text? Do you want to?

I recently completed my first book based on the life of the French female explorer and botanist, Jeanne Baret. It’s yet to be published, and I hope it’ll be the first of many books I write myself.

Diary of a Marine Biologist

By Anita Thomas

Illustrated by Sarah Wilkins

Walker Books

RRP: $27.99

Katherine Hurst

Katherine Hurst has had a variety of jobs including making superconductors and working in visual effects on The Lord of the Rings movie trilogy. More recently she completed a Master of Science in Society at Victoria University, and now works as a science communicator in Wellington.