Following yesterday’s review of Te Ata o Tū | The Shadow of Tūmatauenga (Te Papa Press), Frank Wilson had several conversations with three of its writers—all Te Papa curators—about the creation of the book and how they hope it will be used. A copy of the book was given to every high school and kura in Aotearoa. Sample pages can be viewed here.

In terms of the stories and taonga in the book, Te Papa has such extensive collections—you couldn’t include everything. How did you choose what to include in the book?

Matiu Baker: First of all, I suppose one of the things we had some lengthy conversations about, was trying to get some framing around what are the New Zealand Wars? What constitutes something that would fall within a broad definition of that period of internal conflict between Māori and the Crown? More classically, it would be restricted to something like the 1845 Northern wars through to about 1872. We felt that we could make a strong rationale to extend it to include things like the [attack on the] Boyd in 1809 through to Parihaka and even capturing more recent events of activism and protests which you can see in the latter part of the book where we give some time to things like Mike Smith’s chainsaw from the felling of the trees on One Tree Hill | Maungakiekie in 1994.

…the taonga in the book represent a pretty high proportion of the New Zealand war-related objects that Te Papa has been holding.

Michael Fitzgerald

Rebecca Rice: We’ve also included artists whose work continues to deal with and highlight the ongoing legacies of the New Zealand wars. We’ve included Pākehā perspectives as well as Māori ways of connecting with and thinking back upon those histories to emphasise their continued relevance in the contemporary moment. So while we focused mostly on the nineteenth century, there’s a strong contemporary reflection.

Michael Fitzgerald: To be honest, the taonga in the book represent a pretty high proportion of the New Zealand war-related objects that Te Papa has been holding. I think what we’ve managed to do is cover the key events across the whole period of the wars. We’ve been able to use collection objects to illustrate the human stories behind these episodes. What also pops up is that the human stories embrace the stories of women and children.

Rebecca Rice: Rebecca Rice: We were very conscious that our collection has certain strengths and gaps. There are some stories that are really important to certain people, to iwi, to hapū, to whānau. But we don’t have a taonga, or collection item, that opens up that story. So it was very much driven by the taonga that we hold and the density of some coverage reflects our collection. This book also just represents a starting point, it shouldn’t be seen as the end of our institution engaging with these histories or taonga and the stories associated with them.

Museum collections are often removed from the people they were first associated with. Did you have conversations with the people who have whakapapa with each taonga?

Matiu Baker: We did—well we tried to in every instance, to the best of our ability.

Rebecca Rice: Once we found the right people, or the right overarching iwi body, we made contact to invite their collaboration, feedback or commentary on the book. We had Zooms and met with them first, so we could establish a relationship before following up with the material.

Matiu Baker: It was really difficult at times. Our priorities are not necessarily the priorities or iwi, hapu or whānau, regardless of how important something might be. So we often had to rethink our plans, as we worked through the process of the collaboration.

Rebecca Rice: It really changes the way you think about writing about a taonga when you meet the people who really connect with it. We had this very telling Zoom, I’ll never forget it because it was so good. We were talking with a descendant of Matutaera Nihoniho, whose sword of honour we hold in the collection, and he just said ‘you know, the trouble I have with this writing is it’s as cold as the steel on the blade of Nihoniho’s sword’. They weren’t feeling their tupuna reflected in the writing.

Matiu Baker: We’d already drafted out an entry about Te Kooti Te Tūriki, quite a lengthy one, and approached the whānau. While they were supportive of the project and wanted to have these conversations about their tupuna, they weren’t happy about how we’d framed it out of the mainstream conversations about Te Kooti. There were things they understood about their tupuna that they felt weren’t adequately reflected. So we had to rewrite some of that and that was really interesting, to reframe it to tell a story that was reflective of how this whānau understood their tupuna whilst not departing from what we know of that history at the same time. It’s a careful balancing act. In another instance, I nervously met with a very high-profile Waikato leader, and apart from the odd spelling mistake, he changed nothing; he was completely satisfied with how we represented his tupuna.

We were hyper aware that we were correcting an institutional failure at the time; this is a collection that is built on a colonial legacy of collecting.

Matiu Baker

Michael Fitzgerald: Another example is the incident at Handley’s woolshed (page 265) where a number of children were killed by the Kai Iwi cavalry. We reached out to Handley’s descendants and asked if they were okay with us writing about their ancestor in the way we proposed to write. And they said yes—we need to address these issues, the good and the bad, to try and understand and make New Zealand a better place.

Rebecca Rice: Originally there was an idea that every taonga would have a story from the institution and one from iwi, hapū and whānau. Logistically, that didn’t happen given we ended up including over 300 taonga in the book. So we went with a more consultative approach, which sometimes lent itself to more integration of their perspectives in the text, sometimes resulted in different pieces, and at other times just a spelling correction.

In the end, rather than inviting different viewpoints on every taonga, we thought about the bigger issues or themes relevant to the histories of the New Zealand wars that would complement the contents of the book. So we asked certain historians, artists, makers, writers to contribute thematic essays that would lift up these ideas and give them more flesh. The very personal ways that people ended up writing to these themes surprised us. For example, we asked Jade Kake to write about spatial histories and her writing is all about her people, her lived experiences and her relationship to her whenua and whakapapa that she is actively learning.

Matiu Baker: We were hyper aware that we were correcting an institutional failure at the time; this is a collection that is built on a colonial legacy of collecting. And we did not have enough Māori voices to speak within our own team, there’s just myself. We needed another way to rebalance that. The essays are a wonderful device to bring in not only more Māori voices, but a multitude of perspectives and narratives.

One of the differences that I really appreciated in the book was your critique of the whole idea of Te Papa collecting these things. I didn’t come to the book expecting that. Was that well received?

Michael Fitzgerald: At the very beginning, Te Papa was promoted as a nation building exercise. There was an aversion to deal with difficult or challenging topics. In the 1990s when Te Papa was being developed, the powers that be at the time were really interested in a project that would boost the nation’s confidence and portray a positive image. I think the world has completely changed now.

Rebecca Rice: I think our Kaihautū. Arapata Hakiwai’s preface is quite outspoken about our intentions as an organisation. And I think all of us are 100% behind it.

Matiu Baker: Yes, absolutely. We’re a modern contemporary staff. We don’t wear a colonial mask. We’re a very long way from the Colonial Museum.

For teachers using this in schools, how might the stories help students connect with the histories of their area?

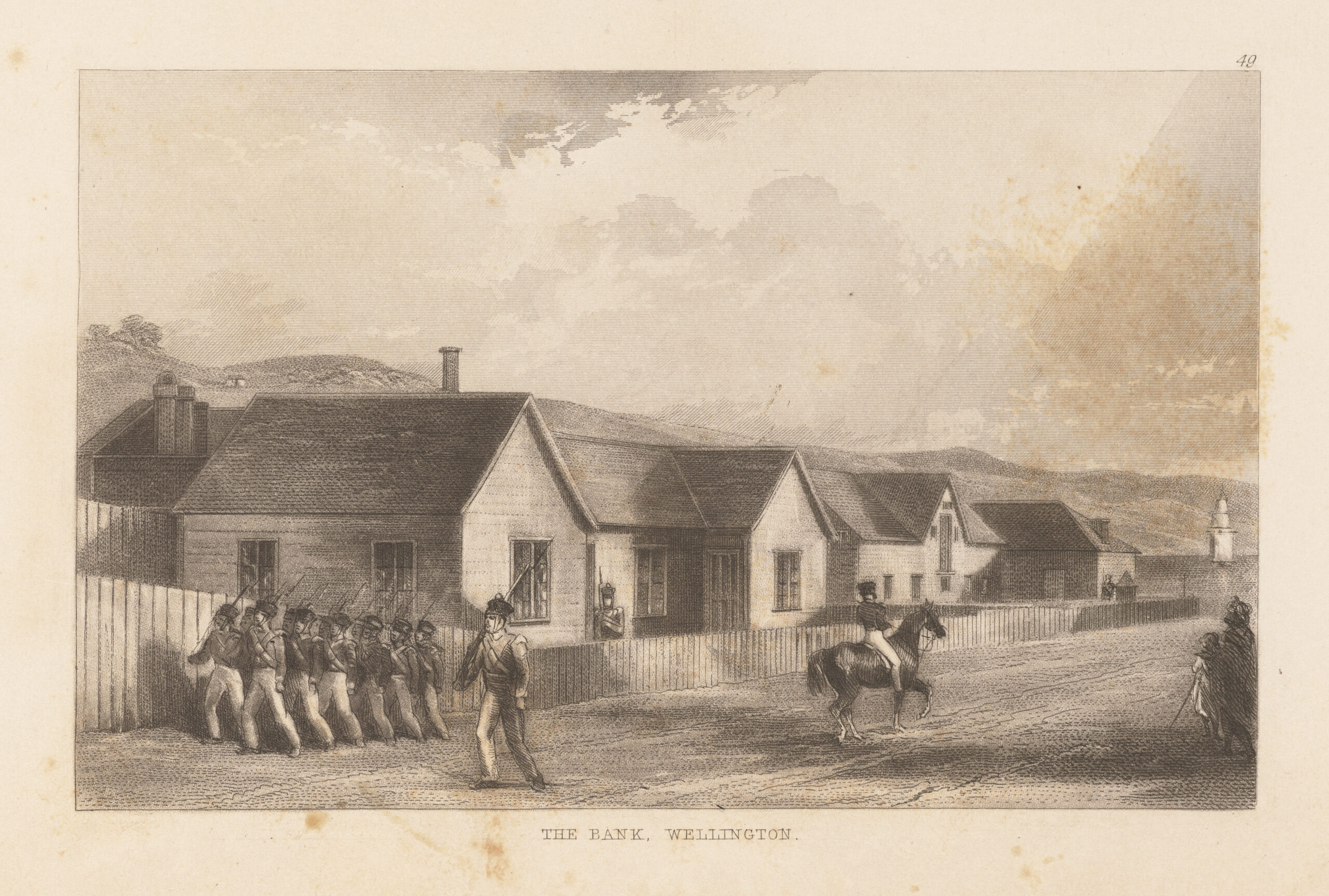

Michael Fitzgerald: Some parts of the country are very close to historic sites. And site visiting can be really important to try and understand what happened on the site, because you can have a copy of an old map of a photograph. You can think about what it looked like at the time, and try to get an understanding of the layout of the sites where these events happened. For example, if you look at a musket used by a young chap called Thomas Mills in the Wellington volunteers. He goes up the Hutt Valley to the stockade at Taitā to join the garrison there. One of his comrades writes about lugging these heavy cumbersome muskets all the way through dense rainforest. The Hutt Valley at the time was an incredibly dense jungle that people had to trudge through, this heavy bush all the way up and down the Hutt River. So there’s an interesting story there of what a different world these people lived in, in terms of geography, vegetation, difficulties of travel, and also the unreliable weaponry they had to fight with.

What are your hopes for how the book might be used in schools?

Rebecca Rice: Well, I hope that they could look at something like this painting (Dr Featherson and the Maori Chiefs, Wi Tako and Te Puni, page 63), and read about it in the book and look at it online. And then think about the complexity of social and political narratives that you can just unpack by looking really closely and thinking about this painting. I gravitated towards art history because I believe in the power of objects and taonga to provide a window into the past. So for students in the school system, I think that talking about history through things—objects, works of art, taonga, photographs— means you’re likely to have a much bigger win than just presenting a whole bunch of written words about a history of an event or a place. I hope there’s enough in here that teachers and students can be curious about the text, the subtext, the histories that resonate around the objects that are presented in this book, and they might get some of that information through the text that’s alongside them. But it might also inspire them to go and read further into it.

Matiu Baker: Absolutely! Taonga are ways of telling stories for me. I want students to read it and engage with it and enjoy it and discover new things about the taonga and about our history.Michael Fitzgerald: Well, I’m hoping that there’ll be teachers who will actively engage their students with the stories in the book, because I honestly think that these are stories that every New Zealander should know. And you go back to some book, like James Cowan’s famous The New Zealand Wars, and you can supplement his stories, and his interviews with people who had fought in the wars, with extracts from Te Ata o Tū. Then I want students to figure out how to do searches and connect people, places, dates or events on Papers Past. You can get into the way people spoke or wrote at the time, and amazing insights into events that you thought you knew all about. It’s quite an astonishing resource.

This book also just represents a starting point, it shouldn’t be seen as the end of our institution engaging with these histories or taonga and the stories associated with them.

Rebecca Rice

Te Ata o Tū | The Shadow of Tūmatauenga

By Matiu Baker, Katie Cooper, Michael Fitzgerald & Rebecca Rice

Published by Te Papa Press

RRP: $70.00

Frank Wilson

Frank Wilson is a lecturer in initial teacher education at Victoria university, specialising in social studies and literacy. She also works for the Aotearoa Social Studies Educators Network supporting teachers to develop their history and social studies programmes.