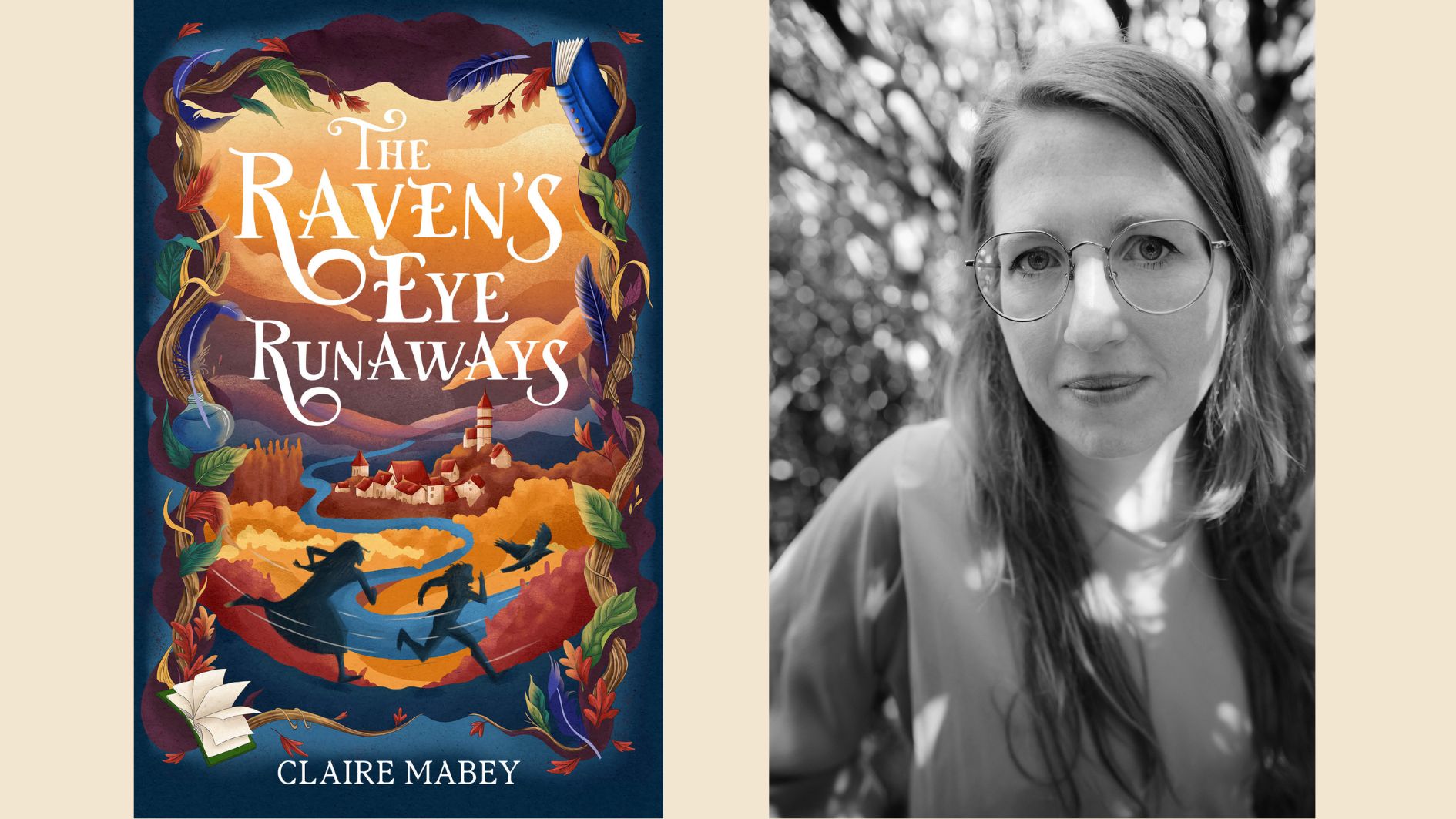

Claire Mabey is one of the busiest people in Aotearoa literature: founder of the Verb festival, books editor at The Spinoff, and now novelist, with an outstanding debut, The Raven’s Eye Runaways. Thalia Kehoe Rowden had a thousand questions for Claire about the book, the writing process, and what Claire will write next, and narrowed it down to a mere dozen for us today, so we can hear her answers on silver birches, witch trials, post-it notes, and killing your darlings.

Claire Mabey credits legendary novelist Elizabeth Knox for sparking the journey of writing this extraordinary book. Elizabeth teaches a course on ‘world-building’, and the fully-realised world that Claire has constructed for her Raven’s Eye heroes is a powerful engine that drives the story and attracts the reader.

We start with bookbinding apprentice, Getwin, whom we know we’re going to love immediately. She’s working ‘Almost certainly past midnight’, as chapter one is titled, alongside her mother, to meet the unreasonable demands of the Stationers’ Company, the powerful guild who control not only book production, but the free flow of any information—and even literacy.

Getwin is tired and hungry, and not at all sure she wants to continue in her mother’s trade. She’s also occasionally blind in one eye, and harbouring a dangerous secret: she can read, despite not being born into the Scholar class.

Somewhere across the country, Lea is a prisoner at Missall House, drugged with other girls to provide mystical writing services—only, lately, her addictive tea hasn’t been delivered, and she’s starting to notice disturbing things about her surroundings. She’s been convinced she’s acting out a religious calling, but should her hands be so bruised and wounded?

Both the dangers and the helpers along Getwin’s and Lea’s journeys are unique and unexpected; you haven’t read this book before.

We’re in a world that takes medieval Europe as a starting point, but with a parallel slip sideways. It reminded me of Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials world, though that is more ‘historical’ with clear analogues, like anbaric power for electric power, and a recognisable Catholic Church that just never had a Reformation.

The Raven’s Eye world has familiar historical elements, like artisan guilds, horses and carts, and leather-bound books with fine calligraphy. But it’s not simply our world with a few substitutions; it’s a whole new place. It has an oppressive religious regime devoted to ‘Prime’, deep magic performed by ancient trees and gifted individuals, and slant-wise takes on patriarchy and poverty. Getwin’s family is on struggle street in some ways, but their house is full of art, beautiful fabrics, and a pleasing amount of cake. Her mother is a respected artisan, and women wear trousers, but there’s a sinister atmosphere of oppression based on gender and class.

Both the dangers and the helpers along Getwin’s and Lea’s journeys are unique and unexpected; you haven’t read this book before.

First things first, Claire: I absolutely inhaled this book, in one weekend, snatching chapters in between parental travel duties—on planes, at bus-stops, in a cold hostel bedroom waiting for the shower. And then it ended on a cliff-hanger! So please assure me you have a plan for another book—or six?

I am so delighted to hear this. I wanted to write a book that got its roots into the reader nice and firmly (the kind of book I loved when I was a kid and that I still love now). There are two more books planned (I’m near the end of writing the second book which has been so much fun!). When I set out on this first book I knew that it was going to be a trilogy. The shape of the story just came that way.

Phew! Glad to hear it. I really need more, particularly because the world-building in The Raven’s Eye Runaways is so masterful. I want to know much more about how this world works! How did you go about creating this place? What do your notebooks look like from when you were figuring out all the little details, as well as the underpinning logic of the society and cosmology?

The building blocks of this world were in my head but it took me a long time to dig them out and see how they fitted together. Books have been a huge part of my life so that element (this novel is a book about books in many ways) just popped out. The whole story started with two scenes: the first about a girl who was being forced to write all day; the second about a girl who had to leave her home. I wrote those scenes randomly, and separately, but was excited by them both. After a while I realised they were part of the same world. From there I kept asking questions of those characters, like: Why are you being forced to write? Why do you need to leave your home? When are you going to meet each other?

Once I had the characters, their world grew around them and expanded out. That’s when I realised I was firmly lodged in a pre-Industrial, Medieval world. I have been fascinated by the Medieval period for a long time. I did a lot of study on it and in my twenties I worked for a publishing company who specialised in Medieval scholarship. So I had that world in my brain.

The key part—and the aspect I had to research for the book—was how books were written and published and disseminated. During that time in our world literacy was low, books were rare and very valuable. They also were part of a kind of ideological warfare. King James I sponsored the famous English translation of The Bible and also wrote Daemonologie, a fact that I find completely fascinating. On the one hand there’s this intention to spread Christian beliefs, and on the other offer problems that Christianity could solve: Daemonologie was basically a guide to hunting witches (really the elderly, ill, unfortunate, homeless—it was a huge exercise in scapegoating). The witch trials that followed haunt me so in many ways and I think my book is a retelling of that moment: how some narratives are helpful and some are really not, and lead to lasting damage.

So there’s history underpinning my world (the Stationers’ Company for example is a true historical structure, but I have bent and twisted it) but I’ve taken it to places that push and prod at the truth to make a new truth and a new set of problems and solutions.

My notebooks are full of names from history, ideas about lighthouses (I went down some amazing rabbit holes), and post-it notes of tangents and backstories!

My core belief is that I want to write the story that wants to be written. I honestly don’t really think about it as a children’s book or an adult book.

I don’t think I’ve read other children’s books that begin with quotes from Hildegard of Bingen (what a hero!) and Katherine Mansfield. But like all the best children’s writers, that’s an indication that you’re respecting your young (and old) readers, and never talking down to them. Do you have any mantras or core beliefs about writing for children that guide your writing and keep you on track?

Hildegard is such a hero! I first met her when I was 19 and in an art history lecture in Dunedin. Our lecturer showed us Hildegard’s visionary images from her work Scivias and they blew my mind. From there I went on and studied her for my honours degree, and I’ve been on a pilgrimage to her monastery in Germany and visited the museum there. She was so extraordinary. I love the way her ideas push against her times but also celebrate them: her concepts of health, the cosmos, the environment and humanity are intertwined and that makes a lot of sense to my mind. So she is a big influence on my life and also on this book. Her concept of god in nature is very much a part of this world.

The Mansfield quote comes from this beautiful idea of writing into an unknown space to an unknown reader and an unknown destination. There are magic books in my novel and to me they have that same sensation. There’s an intelligence behind those magic books that conspires with the readers.

My core belief is that I want to write the story that wants to be written. I honestly don’t really think about it as a children’s book or an adult book. I try really hard to be faithful to the voices of the characters and what they want to do rather than what I want them to do. What I’m hoping for is that their deep humanity will then exist on the page. This sounds so woo woo… but I think I am one of those writers who feels like they’re conjuring up real people. My characters, to me, feel very alive and I want to treat them as well as I possibly can. Then, I think, maybe the reader will become as absorbed as I did when I found the story and these people.

Kate de Goldi often talks admiringly of writers who know how to ‘make sentences’, and you are clearly one of those. Your book is outstanding at the story-engine level, and also right down to the word choice, the poetry and fresh imagery throughout. First thing in the morning, Lea’s eyelids are ‘heavy as porridge’; when Getwin and her best friend Buckle learn some secrets, it feels like ‘the private histories of parents falling over them like old coats tumbling out of a wardrobe.’ The sentences were a pleasure to read, while still being light and nimble. How long does it take you to write a sentence? Are you constantly swapping out metaphors and eradicating cliches, or does the poetry come naturally in your writing? What are your tips for other writers?

Oh thank you so much for saying that. I really appreciate that, so much, because I am still learning about writing. I learned so much writing this book and also discovered how much I don’t know. Even after 35 years of being a reader (which was my training ground, mostly) I realised that when it comes to actually making sentences… phew, there’s a lot to consider!

I think that I over-write, initially. I did lots of drafts of this novel and quite a few exploratory scenes and chapters that didn’t make it to the final version. Elizabeth Knox helped me with a gnarly point of view issue early on (so grateful for Elizabeth’s teaching!) and that was super valuable. I definitely recommend having an experienced writer look over your early draft so they can point out major things before you get too deep. Once I had that issue sorted it all came a lot easier.

In terms of precise words and poetry: I went over and over and over it. To the point where I actually got lost and was like ‘what even IS A WORD?’. But that helped me learn that I do need to make decisions around language with my critical brain: what is the best possible image that will offer the reader clarity? Basically: kill darlings, keep clarity. I think that’s what I learned.

Trees and books are key players in this novel. What are a couple of your very favourite trees and books?

When I was a kid we had silver birch trees and one in particular was perfect for climbing and I loved it a lot. Then it got cut down. I was so distraught it was like losing a pet! So that tree is a lost favourite. Also a magnolia tree that we had when I was a kid—my brother and sister and I used to drink the rain out of the fallen petals and pretend we were fairies.

Favourite books are hard! I think The Changeover by Margaret Mahy, and The Haunting and The Tricksters by her, are favourites. Mahy was a true genius and I am in awe when I read her work. I also love The Boy with Two Shadows so much: that witch is a delight with just enough menace and just enough cackle. I absolutely adore the writer Sylvia Townsend Warner who I’m actually quite obsessed with. Her novel Lolly Willowes is one of my favourite books of all time, and The Corner That Held Them by her comes close, too. There’s an art history/medical book called Medieval Bodies by Jack Hartnell that I love; and also Femina by Janina Rameriz. Both are history books that offer us fresh ways to look at the Medieval imagination. I’ll always love the Anne of Green Gables books (all the way up to Rilla of Ingleside which is about Anne’s youngest child): Anne is probably the first book character I identified with and wanted to be like.

Your conversational, quirky chapter titles are delightful. ‘Chapter 2: Almost certainly after midnight somewhere else’, ‘Chapter 16: A warm bath (and a secret read)’, ‘Chapter 43: Breaking the rules (and windows)’ At what point in the writing process did they emerge?

I’m so glad you liked those! They came in about the third draft and what I realise now is that for me they are the voice of the book itself. The novel has books with real character and I wanted my novel to have a voice, too. I wanted some sense of a guiding narrator throughout the story who would give suggestive peeks about what was going to happen and have a lightness about it. The novel does get quite dark so this voice was about offering an antidote to some of that, and some reassurance.

One of the many people I want to press this book on is a friend who runs a support network for people emerging from cults and controlling religious groups. Lea bravely escapes Missall House, but it’s quite a process for her to disentangle herself emotionally and cognitively from the cult-like regime she’s been imprisoned by and figure out what’s true about her life and the world. Did you have any real-life communities in mind or in the background that informed Lea’s experiences?

This is so interesting to me. When I wrote about Lea I wasn’t thinking of a specific community. But after I finished the book I had this strange experience of memories from my childhood resurfacing in very vivid ways. For a while I went to a very religious school—an evangelical primary school. Some of the lessons we learned there were very stressful for me as a five-to-seven-year old with no other religious context. I ended up writing an essay about it because I realised how much that early experience with the stories intended to control how you thought about the world affected me.

Then I watched the four-part documentary on Gloriavale and could not stop crying. I found it so stressful, and painful and also just so moving. The bravery of those people who left and also the love they still nurtured in them for other people is very beautiful to me. After that I looked at Lea and saw that’s what I’d written: there’s some of me in there (a bewildered child who had to undo a lot of damaging narratives) and then what I’d absorbed from our own world.

What I did think about very hard in the book is the fact that while a lot of what Lea is taught in Missall House is intended to make her world small and scary, there is also some good there. I didn’t want it to be completely black and white. That’s why in one moment Lolly says to Lea that even she can see that some of the Prime myth is beautiful. For me it was important to give Lea some power over those beliefs: that not everything she learned at Missall House was bad or wrong, some of it can be useful and turned to good.

I think there is a universality to the story in that it’s about children discovering adults don’t really know what they’re doing and that they’re going to need to intervene.

Most writers in Aotearoa have other jobs, not to mention family and community responsibilities. How do you juggle all the things in your life with writing novels?

To be honest I had to radically change my working life to let this novel come out. For a long time I was dedicated to making festivals. But those are a huge act of world-building in themselves and I just didn’t have room in my head for novels while I was doing that job.

Once I extracted myself from the bulk of festival-making I found I had so much space in my brain and also energy to direct into writing a novel (which is a marathon). I now work Monday to Thursday on my jobs (mainly at The Spinoff, and a small role at Verb Wellington supporting the incredible team there, and some other bits and pieces) and save Friday for writing.

That way I can think about the book all week, make notes, then hit the ground running on a Friday and get 3000 odd words out. Then I keep going on Saturday morning (while my kid and partner are doing morning soccer!). It’s hard but it also means I can’t wait for writing-day Fridays so I feel lucky to have that.

I thought often of Maurice Gee’s fantasy books when reading yours. Some, like Salt, are set in a completely different world, and some, like Under the Mountain, or the Halfmen of O series are firmly grounded in Aotearoa, and freak us out by uncovering hidden aspects of our own world. Do you think of Raven’s Eye as a New Zealand book? It’s set somewhere that has more in common with Europe than Aotearoa, but are local children going to find themselves and their lives in your characters, do you think?

Maurice Gee has had a huge impact on me, as he has on many of us. I think I’ve read all of his novels for children and am amazed at the breadth of them.

I think of Raven’s Eye as a New Zealand book because I’m a New Zealander. But, I also think part of the world comes from the corners of my imagination that is in Medieval Europe and the United Kingdom and in the folklore of the trees that came from there, and also the witch trials which took place on those lands. My ancestors were from deep, dark Dorset and I spent a lot of time there trying to find some shade of myself in that land. I felt in my bones that I knew that place so I think my novel is from an old part of me that has time-travelled and met familiar echoes of the past, just as much as it is part imagination grown by books and study.

Having said that, I think there is a universality to the story in that it’s about children discovering adults don’t really know what they’re doing and that they’re going to need to intervene. For me that’s timeless and timely.

I’m writing a new novel now that’s set in New Zealand, pretty much on the street where I live, and that is a joyful experience so far. Different to the kind of invention Raven’s Eye needed but challenging and fun in whole new ways.

Thalia Kehoe Rowden

Thalia Kehoe Rowden is a former co-editor of The Sapling, and a Wellington writer and human rights worker. She is passing on a family inheritance of book dependency to her two small children, and is delighted to be part of The Sapling, as it gives her even more excuses to read excellent children's books. You can follow her on Twitter, Facebook, and at her parenting, spirituality and social justice website, Sacraparental.