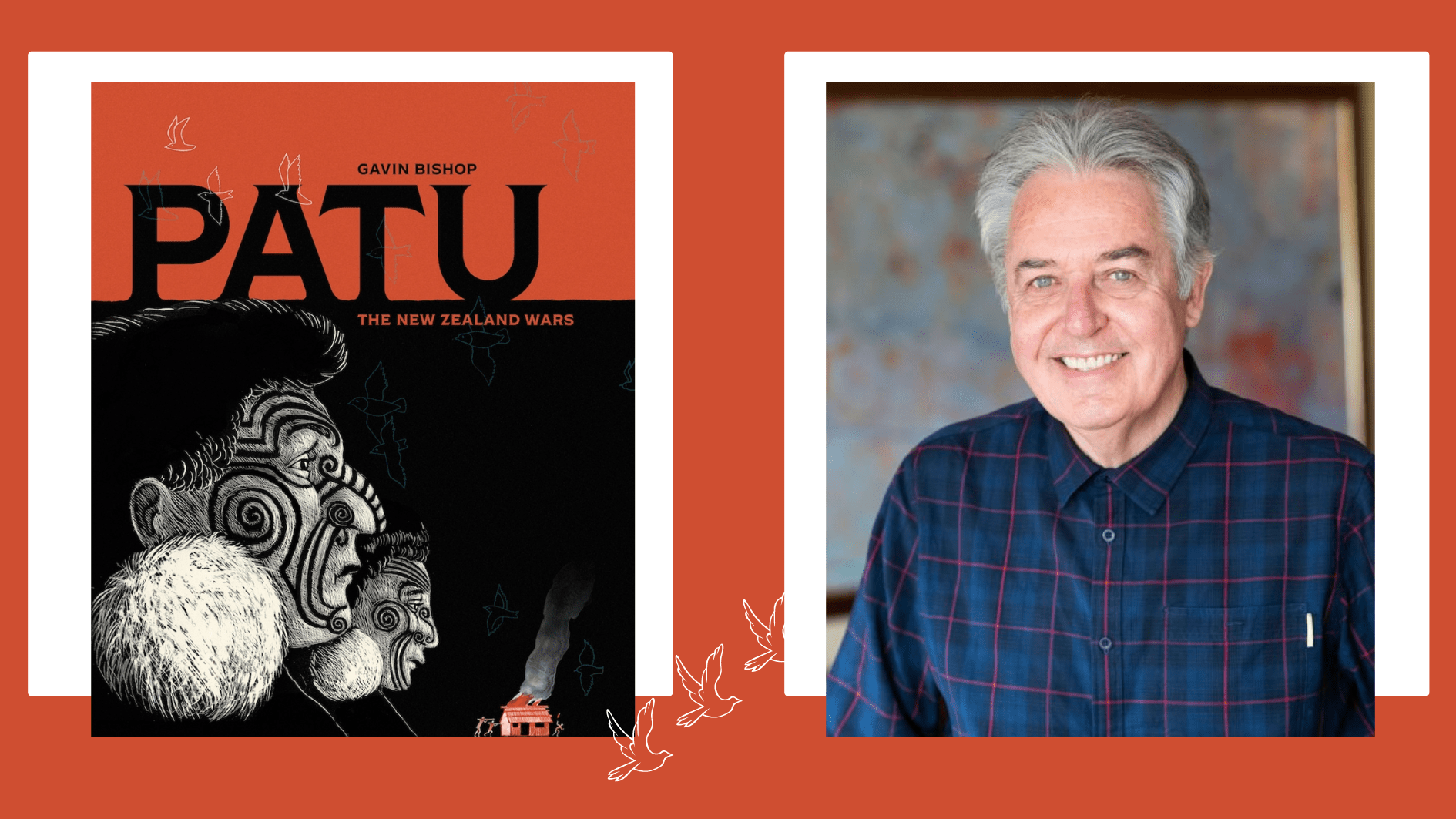

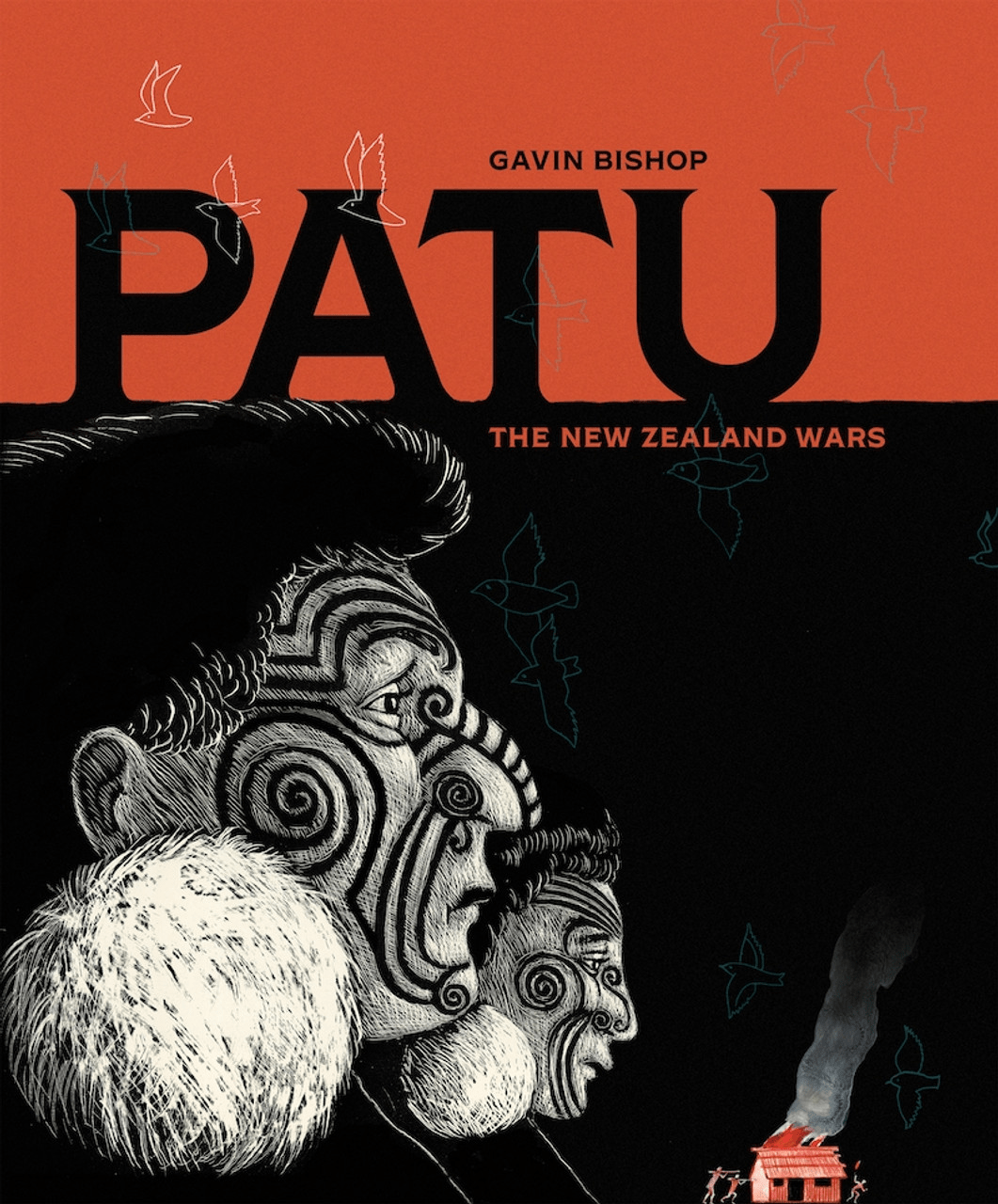

With his latest book, Gavin Bishop (Tainui, Ngāti Awa) delivers a powerful tale of the New Zealand Wars and the painful history of colonisation in Aotearoa. Simie Simpson (Te Ati Awa) talks with Gavin about Patu and how it came to life.

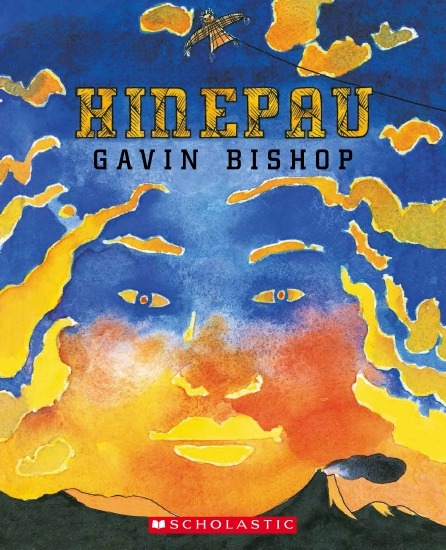

Simie: I have to confess I am a bit of a fan girl; the first books of yours that I read (and bought) were Hinepau and The House that Jack Built. I still have them, and I actually re-read them after reading Patu because it reminded me of them both for different reasons. Can we start by talking about your early influences? What drew you to writing and illustrating, and, in particular, what drew you to create children’s books? Was there anyone who influenced or encouraged you?

Gavin: From as early as I can remember, I wanted to be an “artist”. I think I saw it as a way of avoiding the limited and boring jobs a lot of adults, especially men, filled their days with when I was a child in the 1950s. Being an artist seemed to be an escape route from adult drudgery. I had no idea what an artist did though, and the only real art I had ever seen was signwriting and advertisements on the shop walls. I had never seen a real painting. A few of our friends had framed prints of galloping horses or Scottish castles on their walls. We had a big framed photograph of my mother as a young child and it hung in the spare bedroom that my grandmother stayed in when she visited from Invercargill. Works of art were not a big part of my life, but I was good at drawing and lots of people told me so. I took art as a main subject throughout school and later at university in Christchurch. Writing and illustrating for children came into my life in the late 1970s when I was a young high school art teacher. One afternoon, someone told me that Oxford University Press in Wellington was looking for some new children’s books with a strong New Zealand flavour. So that very night I started writing my first book, Bidibidi. I had no idea what I was doing but I was prepared to take advice and criticism. It was a long road of discovery, trial and error and dead-ends. Bidibidi was eventually published by OUP nearly five years later.

Your whakapapa is woven through your stories. Was this something that you thought about consciously—in that you wanted to tell the story of your whānau, or did it just sort of happen that way?

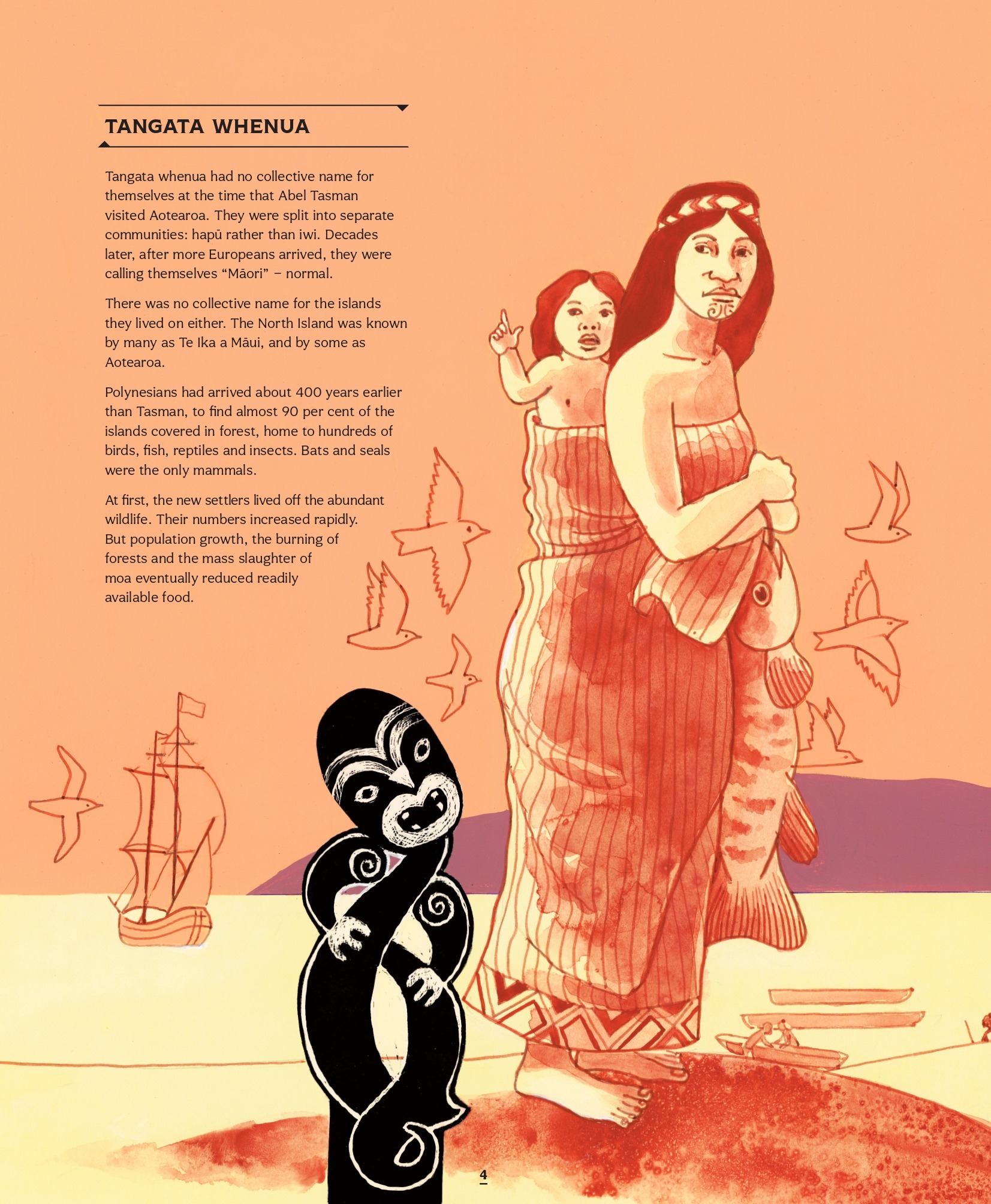

My whakapapa is something that has quietly presented itself to me in little pieces throughout my life. When I was a child I was aware of having Māori connections somewhere “up North”. A couple of my mother’s sisters were obviously Māori but no-one seemed to acknowledge it. A kete of muttonbirds arrived at the back door each year but I didn’t know that it was a gift from some of my mother’s southern whānau. And I certainly had no idea of the significance of my mother’s names, Irihapeti and Hinepau. I did not know they belonged to her grandmother and great grandmother.

The first conscious effort to talk about my whakapapa in my work was in Katarina. This story looks at the life of my grandfather’s sister who followed her Scottish husband from the Waikato to live in Southland in the 1860s. Much of the biographical information in this book was based on scraps of stories I heard around the dinner table when our extended family got together and reminisced.

My whakapapa is something that has quietly presented itself to me in little pieces throughout my life

And on the topic of conscious verses unconscious decisions, have books ever surprised you—that is, has a book you’ve created ever turned out very differently than what you expected?

Most of my books rely to a large extent on my subconscious. I think it is a creative process that most writers and artists use. I have come to rely upon it a great deal. There are the practical things about writing and illustrating such as getting the text in the right place on the page, allowing the pictures to help tell the story and so on, but there are abstract things that the conscious and practical mind has no control over. If you are lucky these contribute the magical factors that can lift your work out of the ordinary. And these things often don’t present themselves until the book is published and been around for some time. It is these things that can make your work special and hopefully unforgettable for the readers.

When I re-read Hinepau and The House that Jack Built, it felt like Patu was part of a journey, a journey of you as a writer and illustrator, but also it felt like a progression of publishing in Aotearoa. Can you talk about the changes you’ve noticed in your own work and any you might have noticed in publishing since you started?

Just about all of my work is linked in some way. Some of the links are obvious in that they refer to my obsession with telling NZ stories to NZ children. And some of the links are obscure and are only found in my sense of humour or the types of characters I like to write about.

Some of the biggest changes I have seen in publishing for children in this country are the number of books now being produced here and the growing confidence to use local settings and histories. When I was a child most of the books I got from the library or read at school came from England, the USA or Australia. Only a tiny handful were written and published here. It is completely the opposite now. Another big change is the quality of our books. In recent years the writing and illustration in the best NZ children’s books is as good as any in the world. And one of the most important factors in making this happen is the improvement in book design.

The writing and illustration in the best NZ children’s books is as good as any in the world

The House that Jack Built, like Patu, describes colonisation and the effects of colonisation of Aotearoa, both in quite different ways. Do you feel like these two books are connected/complement each other? Do you think you could have written Patu when you published The House that Jack Built—or, as a writer, do you think your other books have led you to this?

The House that Jack Built, set in early New Zealand, was an idea I had for some years but its publication was delayed by other books based on this nursery rhyme being produced in other parts of the world. (This famous rhyme has been used to talk about all sorts of things from drugs to serial killers.) In 1996 I was living in Boston, teaching at the Rhode Island School of Design. I took my idea of using this rhyme to tell the history of the European settlement of Aotearoa to a Boston publisher. They told me they liked it but I should take it home to NZ and have it published here. So I did.

Patu is a much more complicated book, and to some extent was made possible by the experience of writing my earlier “big” books such as Aotearoa, Wildlife of Aotearoa and Atua. They all helped prepare the groundwork for this book.

You clearly did a lot of research for Patu. Can you talk a little about what motivated you to write Patu, how you research, how long it takes, and how you distill all that research into a book?

Patu took me about three years to research, write and illustrate. I am not an historian. I am more of a compiler and a storyteller. Most of the details in this book, except for the whakapapa and perhaps the introduction, came from the work of professional historians who have written about the conflict between Pākehā and Māori since the 17th century. I made lots and lots of notes before writing the first draft of the text, which of course was far too long. The next big job was to whittle the text down. My editor, Catherine O’Loughlin at Penguin Random House, helped with this. Once I could see where the text would fit on the page it was time to plan the pictures. I produced these in several stages. The portraits for example were all done separately as scratchboard drawings from photographs. This took several months. I then photocopied them and added them to the painted backgrounds of the final art.

I think regardless of how neutral historians aim to be, they can’t help but bring their own perspectives and worldview into their work. The history of the colonisation of Aotearoa has been told, largely, by Pākehā historians. How do you think this affects/influences your research?

I find some of the recent histories written by James Belich and Vincent O’Malley very approachable and sympathetic. I used these a lot because they were clearly written, well paced and easy to follow. Some of the earlier New Zealand Wars histories, however, are not so easily digested and some are downright racist and bigoted. Even so, they often capture a feeling for the times that they were closer to when their books were written.

My challenge was to read as much material as I could, digest it and rewrite it for a young audience. The skills I have developed in 45 years of writing concise texts for picture books was invaluable.

I am not an historian. I am more of a compiler and a storyteller

Was it difficult reading some of the research? I found some of Patu very hard to read; your text is clear and concise but it hits really hard. Lines like “The battle site is now a golf course” and the explanation of how the establishment of native schools was a way to lead Māori to sell more land are deceptively simple and factual but they say so much about colonisation.

I wanted my text to be direct, honest and unforgettable. I took care not to dwell on gory details just for the sake of it but I selectively chose several unpleasant incidents to impress upon young readers that what went on for a very long time was bloody awful.

There’s always a lot of debate about what is ‘appropriate’ for children in books. I find this interesting in general as the same lens is seldom applied to anything other than books. However, do you think about your audience when you are writing? Do you think some things are too difficult for children to read about? And who do you see as your audience for Patu?

The audience for Patu is older children. The book looks like a children’s book with the text scattered across large pages with lots of pictures. However, this book has also been very popular with adults and lots of my acquaintances have asked, “Why weren’t we told this when we were at school?” And some say, “In New Zealand history classes all we were told about was ‘Good Governor Gray’ and the lovely English settlers who brought potatoes and pigs for the Māoris to eat.”

What do you hope will be the takeaway for readers of Patu?

I hope it is an eye-opener for lots of people—children and adults.

What comes first, the chicken or the egg? Did you visualise this book as an artist first or a writer? And is that the same for every book you have written? If you illustrate after the text is completed, how do you decide what to illustrate? What do you want the illustrations to convey to the reader?

Generally I write the text first, for practical reasons. In a book for children the number of pages is set by the publisher. Most picture books are 32 pages long. Basically the reason for this has to do with money. A 32 page book can be economically printed on one big piece of paper. Patu has 64 pages – two regular picture books in one. The number of pages determines the amount of text you can use so it pays to get that sorted before you start producing any pictures. You can do some roughs and perhaps make a storyboard to show where the text and the pictures might go but until the text is finalised and even typeset it is not a good idea to do any final art.

When it comes to deciding what will go into the pictures I usually try to complement the information in the text without repeating it. It is good to get the text and the pictures working to tell the story together in their own ways.

This book has also been very popular with adults and lots of my acquaintances have asked, “Why weren’t we told this when we were at school?”

Patu is such a visually striking book—and not just the size of the book, but also the larger illustrations combined with highlighted pictures and the detailed background pictures that have so much going on. It doesn’t look cluttered on the page, despite the detail. Do I have a question here? I guess I would like to know how you do that! There’s also a very strong use of colour throughout; can you talk about the colour palette for your illustrations?

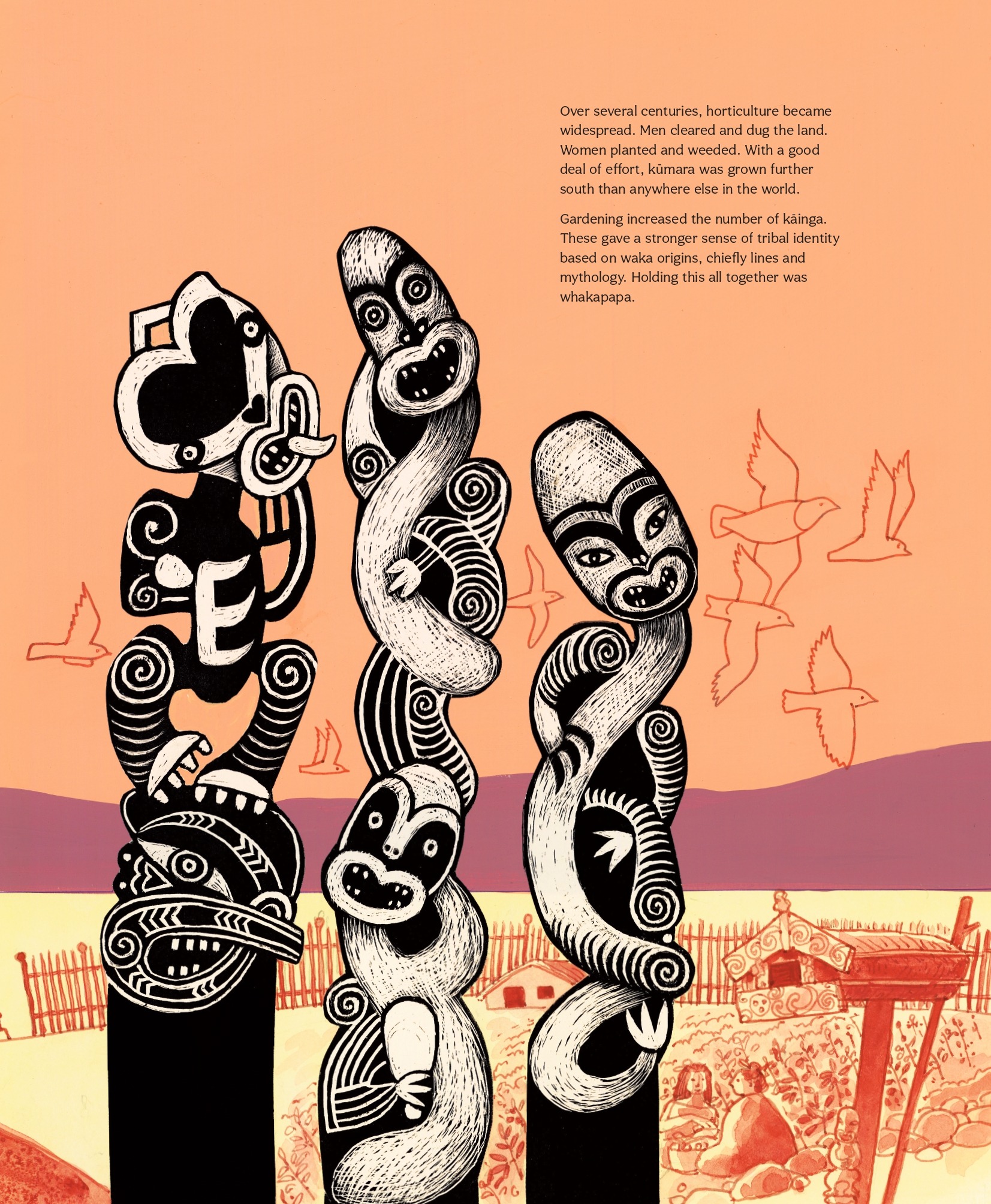

I decided to restrict the use of colour on some pages because of the complexity of the text. I thought it might help tell the stories more clearly. I also thought it would be more dramatic if some pages were predominantly orange or black or blue. I am very old-fashioned. All of the pictures are made by hand. I don’t use a computer to make artwork. All of my illustrations begin with pencil on paper and to that I add ink, paint, collage, scratchboard images and/or prints. Final art is made on water-colour paper that I usually wet and stretch onto drawing boards. It is a long process but it gives me lots of time to think about my pictures and how I want them to look.

Can I ask a few quick-fire questions? What does a working day look like?

On the days I am working on a book like Patu I usually start around 9 o’clock and work all day until about 4.30 pm. I work very intensely, not listening to any music or even the radio. I can work like this for weeks at a time. However, there are other times when I don’t do much at all. I might go to the gym, go out for a cup of coffee and a good cheese scone or go to the movies. I do quite a bit of public speaking to U3A [University of the Third Age] groups and sometimes I visit schools.

What would you say to kids who want to become writers or illustrators?

The obvious, read lots of books and draw a lot. You have to become very comfortable with books and understand how they are made and put together. Become a good storyteller. Movies can be helpful too because of the way they use language and images to tell a story. I watch a lot of movies and always have done. The first movie I saw was the Walt Disney version of Pinocchio when I was four. It was terrifying but I was left with images I have never forgotten.

All of my illustrations begin with pencil on paper and to that I add ink, paint, collage, scratchboard images and/or prints

Do you start thinking about your next book before you finish your current book?

Sometimes, but I don’t usually start working on a new book while the current one is incomplete.

Are you working on anything you feel ready to talk about at the moment? I’m looking for a teaser here!

I have two publishers, Gecko Press and Penguin Random House. I have been doing “babies’” books for Gecko and “big” historical books for PRH. I am currently having discussions about possible projects with both publishers but we haven’t settled on anything definite yet.

What do you like most about what you do?

It is very nice being able to work from home, going to work in my slippers. I have a studio where I can spread everything out and leave it. Much of my time is spent on my own but there are other times when I get to work with some very interesting people such as my editors and designers who bring new dimensions to my work.

What do you like least about it?

Not being able to leave some of the problems you can’t solve behind when you leave the studio. That subconscious I mentioned earlier can be constructive and creative but it can also keep nagging at you when you are trying to get on with something else, like going to sleep.

Looking back at your career to date, is there anything you would do differently?

I should have spent more time learning te reo Māori. I would like to be a fluent speaker.

Do you have any current favourite artists or writers?

A few of the books I have enjoyed reading in recent months are The Deck by Fiona Farrell, Birnam Wood by Eleanor Catton and The Children of Ash and Elm: A History of the Vikings by Neil Price. Artists? There are lots of people whose work I really enjoy. Some make work for adults and others make pictures for children. William Steig, Marc Chagall, Maurice Sendak, Quentin Blake, Arthur Rackham, George French Angus, Lane Smith, Ron Brooks, David Hockney, Piero Della Francesca. I could go on and on.

Are there any books you’ve read that you wished you’d written?

There are many but none more than The Hobbit by J.R.R. Tolkien.

Finally, are there any questions you wish people would ask you and they never do? And if so, here’s your chance to both ask it and answer it!

I can’t think of any that I could to ask and retain my modesty.

Simie Simpson

Simie Simpson (Te Ati Awa) has worked in the New Zealand book industry for almost two decades, as a librarian, a sales manager for Walker Books New Zealand and a bookseller. She is the programmes manager for Read NZ Te Pou Muramura.