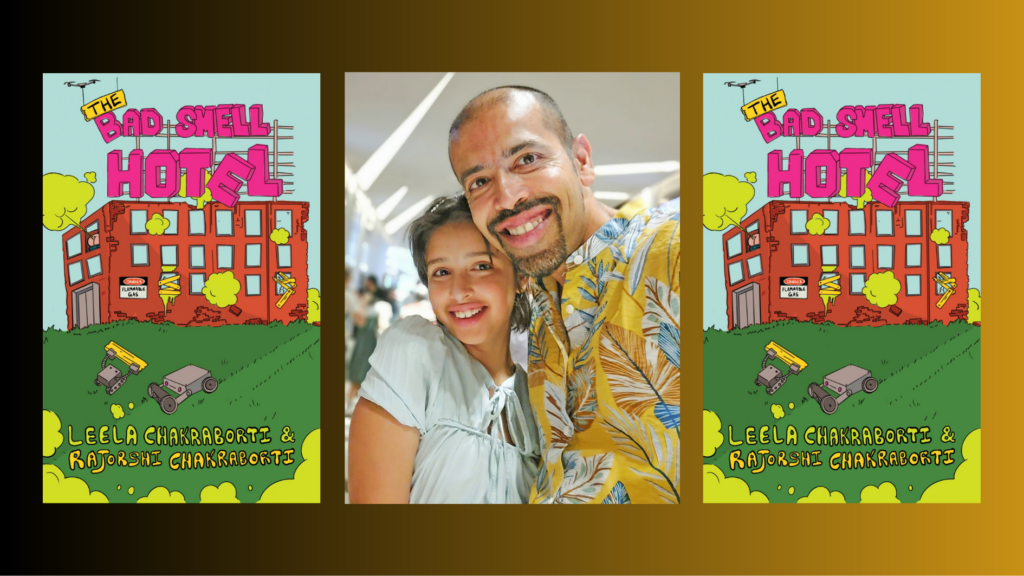

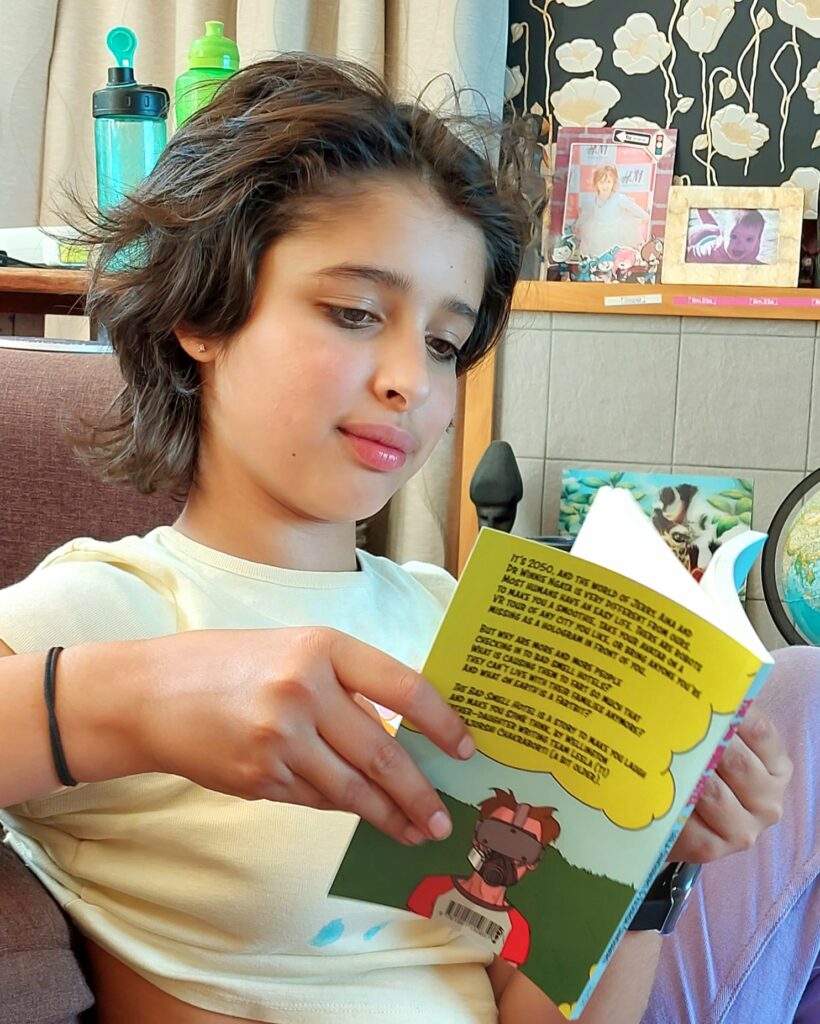

Leela Chakraborti (11) and Rajorshi Chakraborti are the daughter and dad co-authors of The Bad Smell Hotel, published by The Cuba Press. Rajorshi is the author of five novels and a short fiction collection for adults, and a young adult mystery called Mumbai Rollercoaster, which received an honourable mention in India’s Crossword Book Awards. The Bad Smell Hotel is Leela’s first book. They sat down ahead of their launch at Karori Library on 6 April to talk about how they wrote the book together. Leela and Rajorshi live in Wellington.

Leela takes the first bite of her halloumi sandwich – we’re in a café after school talking about our book – and I tell her that it’s funny how I remember the walks, while she remembers discussing ideas on the couch before writing them down. Both memories are true: they were the two halves of our writing process.

‘It’s because you like walking more,’ Leela says, which is definitely the case.

But she does remember something else I bring up. That at the start of several of our walks I would promise her that very shortly something magical would occur which she was going to be part of.

Each afternoon, when we left the house, we had no idea what would happen next in our story. By the time we returned, we always knew. The scenes came to us as we chatted during the walk.

my entire writing life has been based on this magic – of taking a walk, whenever I’ve been stuck, to figure out what the next paragraphs would say

I tell Leela that my entire writing life has been based on this magic – of taking a walk, whenever I’ve been stuck, to figure out what the next paragraphs would say. What was extra-thrilling for me as we came up with the story of The Bad Smell Hotel – besides the joy of doing so with her – was to find that it can also happen in tandem.

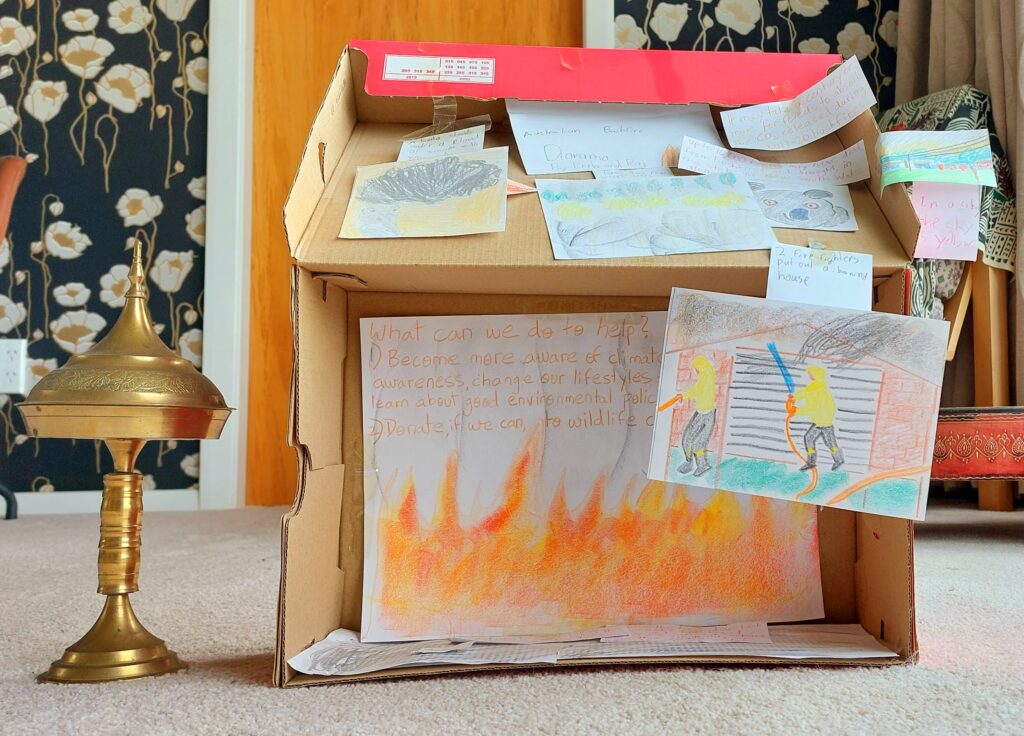

‘I literally felt less locked-down while we were writing this. Because it was so much fun,’ I say. Leela nods, then reminds me of another lockdown project from early 2020, a diorama we made together on the devastating bush fires that had just happened in Australia.

‘And don’t forget the Garden Cup,’ I exclaim, referring to a fiercely contested backyard cricket trophy between India (represented by me), New Zealand (represented by Leela), and Canada, which occasionally dropped by in the form of Leela’s mum, Sasha. New Zealand had a fearsome fast bowling attack, partly because they almost halved the length of the pitch whenever they bowled; India had the more reliable batting. India held the Garden Cup for much of that first lockdown, but right at the end, in a thrilling encounter, New Zealand wrested it away and held it for almost a year until the next edition in the summer holidays.

There you go – Leela will groan when she sees this bit – her dad taking any chance to ramble on about cricket.

‘Do you think the lockdown entered our story,’ I get back on topic. ‘For example, in the way these characters who produced bad smells were being locked down?’

‘Maybe,’ is her reply. I point out another connection that was first remarked on by our publisher, Mary at The Cuba Press – the sort-of resemblance between the Bad Smell Hotel in our story and the MIQ system that began in April 2020, actual sealed-off hotels in which people had to quarantine upon entering Aotearoa.

‘Sometimes, books can do that without trying to,’ I say. ‘I don’t remember us consciously thinking of MIQ hotels.’

‘We really liked the title The Bad Smell Hotel,’ Leela recalls, accurately. ‘And we wanted the story to be about that.’

Next, I ask about Mrs Knickerbocker, the substitute teacher character in The Bad Smell Hotel, and one of Leela’s many contributions to the story.

‘What year was I in when we wrote it?’

‘Year 4. Mrs T was your teacher.’

That’s how it emerges that Mrs T was an important model for the character of Mrs Knickerbocker, in how attentive she always was towards her students.

I ask Leela: ‘As a primary school student now, was it a scary future for you to contemplate, one where all learning is done through robots?’

‘Yeah, because a teacher can help you with strategies that they found useful when they were a kid, whereas robots obviously didn’t grow up, so they don’t have any experiences of being kids.’ I quickly note in my phone that Leela’s making a huge point about the irreplaceability of empathy.

‘Tell me more about what it was like for you to try to see thirty years into the future.’

‘It was cool,’ Leela answers, then casually makes another massive connection, that ‘in the 80s and 90s people never could have predicted the Internet, and maybe some breakthrough is coming that we can’t see.’ Then she asks for my thoughts, because ‘you’ve actually lived through all those changes’.

‘I’m stunned. You’re absolutely right. I was 12 when 1990 rolled up, and if you had told me that by my mid-thirties I would be carrying a device in my pocket with which I could take photos, make video calls for free to people around the world, watch movies, book a flight, find our way around an unknown city, show you your uncle’s wedding pictures, pay a credit card bill, get into an argument with total strangers whilst ordering our weekly groceries at the same time as well as 62 other things that I don’t even know, I would have called you crazy. Not a single show set in the future that I grew up watching predicted any of this.’

So, we agree, we can’t possibly know much about 2050, except to guess that the rate of change between now and then might be even faster.

Leela has finished her sandwich and asks if she can have an ice block. I still have a couple of questions, so I agree. She comes back with a pink lemonade ice block.

I share what I’ve been thinking about while she was away. ‘You know, ever since I first gave ChatGPT a try, I’ve been feeling like some parts of our book are going to get here a lot sooner than 2050.’

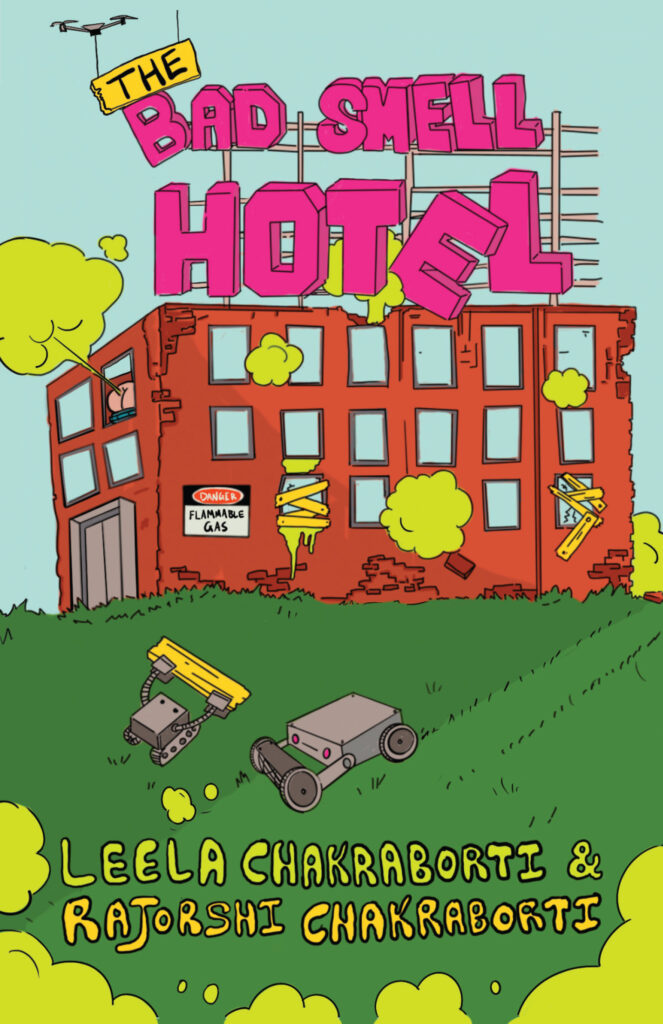

‘Can we tell people how we got our illustrator?’ Leela asks.

‘Absolutely. Tell me how you remember it.’

‘We went to see Mary, Paul and Sarah, and Dan was sharing their office, and they had found out he was an illustrator and liked his drawings. They gave him our book to read and he liked it and made some sketches.’

‘And we liked them straight away, didn’t we? I still can’t believe our luck, that Dan just happened to be working next to them.’

I ask her what creates the colouring in her ice block. Raspberry or strawberry, Leela guesses, then looks at the packaging, and says, ‘Huh, beetroot.’ In vegetable form, she isn’t a fan of beetroot.

As we get up, she tells me that she gave a signed copy today to her school librarian.

‘Was she pleased?’

Leela nods. ‘She said it was the first book she’d received from a student who was also the author.’

I’m very moved, and remind her that it’s another librarian who suggested hosting our launch at Karori Library, because she remembered Leela coming in to borrow books over many years and is delighted to see that she is now an author.

‘Do you think we’ll write another book together?’

‘Maybe,’ Leela replies. ‘But not if we have to walk every day.’

‘But it’s the only way I know of taking a story forward.’

‘We could try asking ChatGPT for ideas,’ Leela says in an entirely normal tone, then does a fake gasp of horror before breaking into a grin.

As we walk to the car, I’m shaking my head at how plausible her suggestion sounds. Suddenly, the world of our book seems a lot closer than 2050.

The book launch for The Bad Smell Hotel is taking place on 6 April, 5.30pm, at the Karori Library in Karori, Wellington.

The Bad Smell Hotel

By Leela Chakraborti & Rajorshi Chakraborti

Published by The Cuba Press

RRP: $25.00