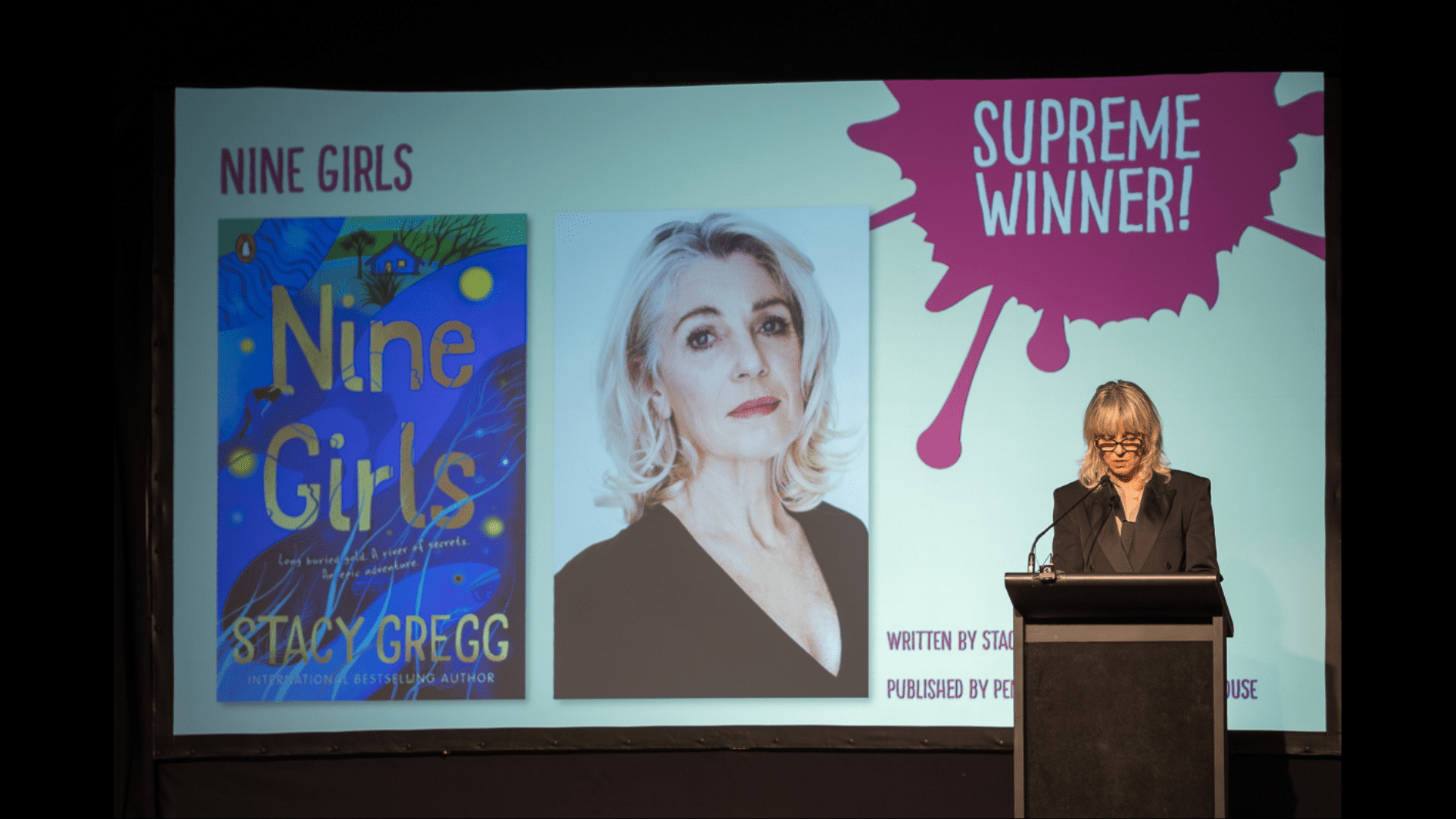

2024 judge of the NZCYA awards Belinda Whyte in conversation with Margaret Mahy Award winner Stacy Gregg.

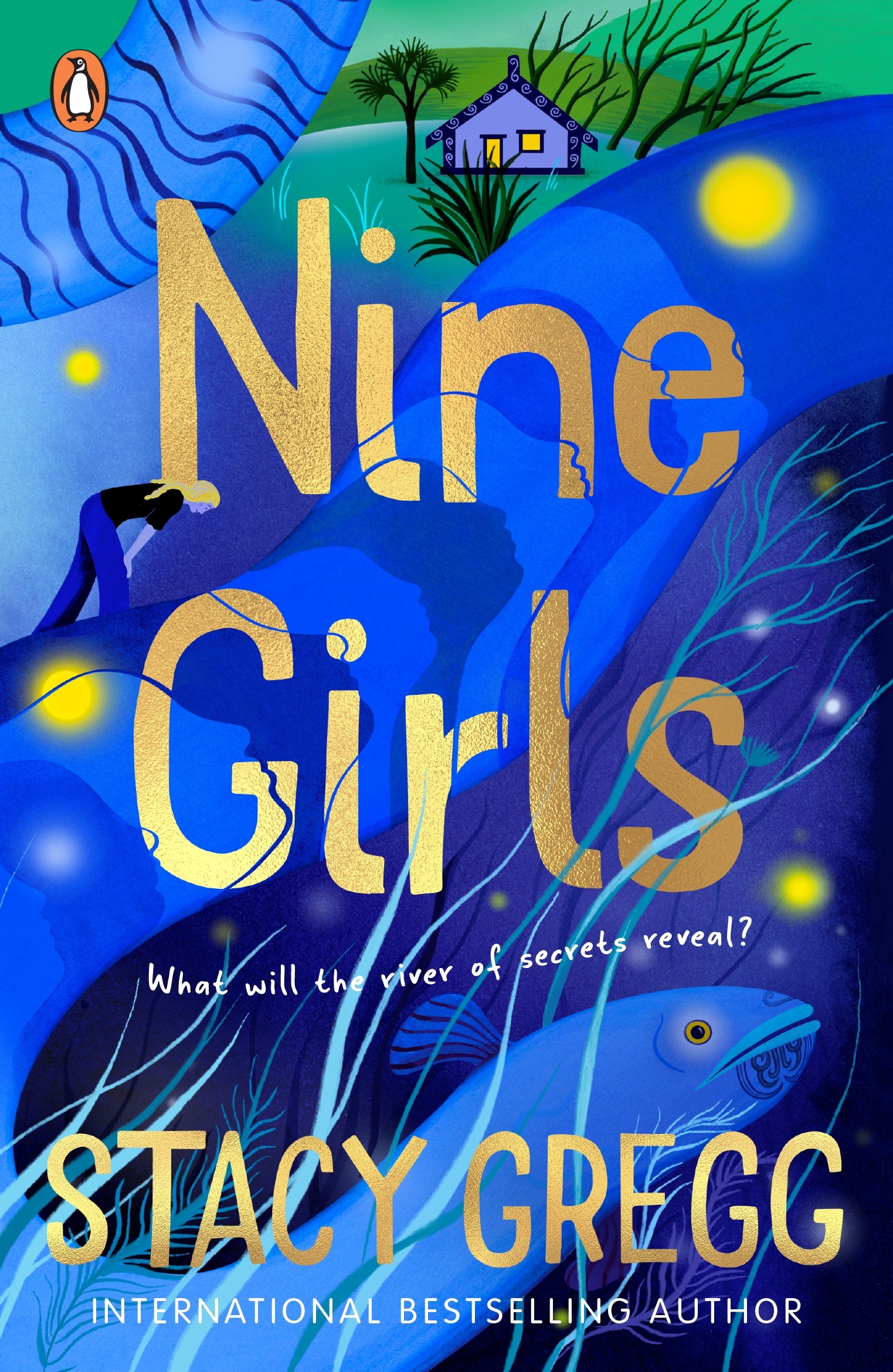

I’ll be honest with you, I had never read a Stacy Gregg novel before reading Nine Girls for the judging of the 2024 New Zealand Book Awards for Children and Young Adults. I was half expecting not to especially enjoy it (sorry Stacy!) because I wasn’t a horse-person, but I knew Nine Girls was something special as soon as I got my hands on it. From the exceptionally pleasing blue-green cover from Sarah Wilkins (Stacy’s favourite cover ever!) to the exemplary writing and meaningful story, it didn’t disappoint.

Nine Girls is a cleverly constructed, loosely autobiographical novel that had me hooked from start to finish. It portrays the complexity of growing into who you are outstandingly well and stood out as a front-runner in the awards from early on. Everything about it felt like it spoke to the New Zealand experience authentically and with characteristic kiwi humour. There are so many layers and significance to this book that make it sure to become a New Zealand classic.

Belinda Whyte (BW): We [the 2024 NZCYA judges] all knew, immediately, when we were reading Nine Girls that it was obvious how important the book was. I felt, ‘Ah, yeah, this is the book we’ve been waiting for!’ I think Aotearoa has been waiting for this book. And, actually, it seems like a book that maybe you’ve been waiting to write? But quite a step away from your other published works—30 books about horses!

Stacy Gregg (SG): More than 30, maybe 30 about horses, and a few with dogs and cats.

BW: How did that change come about?

SG: I can’t tell you whether it was learning the reo or whether it was a chicken and egg situation. I really knew I needed to get back to the stories of my tūpuna and my whānau, I just didn’t quite know how to get there and I felt so ill-equipped. And now, I’m doing full immersion for my fourth year.

I’ve got a couple of older cousins, and I’ve become really aware that we are the mātāmua [first born] of each branch of the family. I was really aware that the stories were starting to get lost. We would talk about things, like about my tupuna, who’s buried up on Taupiri Mountain. I asked, ‘Where is the grave’? And they were like, ‘Oh, Les knew that, but he’s dead now’. I felt like I had all the pakiwaitara [stories] that my Nan had told me, and me and my two other mātāmua cousins; we were kind of the only ones paying attention. I thought maybe I just needed to kind of stitch it together into a narrative.

We operated very much as a Māori whānau, even though we were disconnected from our Taha Māori [Māori identity]. I wanted to write about that, and about colonisation. I also wanted to try and inhabit the mind of my tupuna [Irihapeti Te Paea Hahau Te Wherowhero], who’d gone through what she did at Rangiaowhia [being a loyalist to Governor Grey]. I didn’t want to justify her, but to try and make sense of it. And I think I have made sense of it for myself. If anything, I feel like, ‘who am I to judge?’. She had 15 children. They’re all, in the vernacular of the time, ‘half caste’. They’re Scottish on their two dads’ sides. They’re Māori on her side. They belong in neither world. What path did she have?

BW: I found it all fascinating. You pick up on something I noted; Titch talks about how her Nan ‘stops being a Māori’. The book is full of the effects of colonisation on Māori. What message were you hoping to share with that theme in the book?

SG: I think it’s about having something taken off you and knowing you can get it back again. There’s been a lot of discussion amongst my whanaunga [relatives] about how my Nan and other family members from her generation would feel about things like studying te reo. She was whacked with a ruler at school if she spoke Māori. And that’s very much a euphemism for the actual torture that went on in schools for young Māori kids who expressed that Taha Māori in any way or form. You didn’t have a choice—you had to survive in the Pākehā world or stay over at the Pā. There was no middle ground, and she made her choice. I think there was a lot of grief because of that, masked as ‘I’ve made the right decision’. Every now and then something like Te Karere would come on and I’d ask, ‘can you understand what they’re saying?’. And she’d say, ‘yeah’. But she would never pass it down.

BW: I know a lot of people for whom this book has resonated deeply, both young and older. They all seemed to recognise someone or something and they absolutely loved it. Did you have anybody in mind when you wrote it?

SG: Well, I think that I consider my wheelhouse to be middle grade. I feel like I can occupy that space. This book is unusual as it’s a coming-of-age story as well. That kind of tips it into YA, but it has no YA themes whatsoever. I very much consider it to be middle grade. But I guess there’s a magical thing to middle grade, where you can write something that crosses over, and it’s an adult experience as well.

The whole way through I was hoping to achieve that—if you’re eight years old and you read it, it’s just a gold hunt with an eel. And then you’ll come back to it when you’re 12, and you’ll see it’s more than that, it’s about this girl finding her place in the world. And then you’ll come back to it when you’re 30, and you’ll go, ‘oh, it’s the Tainui wars, and it’s Rangiaowhia, and it’s the Springbok tour, and it’s Bastion point’. I was hoping that it was a book that you would get different things from at different life stages. And then it occurred to me that it was potentially a giant Frankenstein’s monster, because it’s all these things sort of stitched together!

…there’s a magical thing to middle grade, where you can write something that crosses over, and it’s an adult experience as well.

BW: But woven really well! That was one of the things the judges noticed, all of those layered stories come together very well. I really love how it speaks to finding your own identity. Reading about Titch growing into her sense of self and her place in the land was just so beautiful. I presume a lot of it comes from your own life?

SG: Absolutely. My mum did tie a rope around my waist and throw me in the Waikato River so I could learn how to swim with the current! That sense of land and place. I went back to Ngāruawāhia for three months when I was writing the first draft of the book. I borrowed a house off my cousin down by the Waipā River, which is not my normal hood.

My normal hood is over the other side by the Waikato, right under the Hakarimatas. You feel an almost biblical oppression from that mountain range, it sits really heavy. On a winter morning when the grass is covered in frost and the mist is really heavy, it’s quite an oppressive and really powerful place to be. That was really important when I was writing because it just took me straight back to what it had been like as a kid, to feel almost corralled by everything. You’ve got the dump at one end and the marae at the other end and the Hakarimatas looking over you and the river is just so daunting. There’s a powerful iconography in a landscape for a young person growing up. You feel like the land is almost pinning you down.

There’s a powerful iconography in a landscape for a young person growing up.

BW: You can feel that, yeah. I can imagine you would also feel your tūpuna kind of surrounding you and maybe you don’t recognise it at that age but you do later on.

SG: Yeah, and definitely some of the events, like the Rugby Park Springbok match, my mum did take me to that. I remember being gut-wrenchingly terrified because it was so violent, and the protesters were all around and it was like suddenly being in a war zone. All I wanted was to get out. But Tania in the book, obviously, you know, she’s got nothing to lose, and she’s on a mission. She doesn’t have that same sense of fear. I did not storm the pitch; I was trying to get off the pitch!

I remember being gut-wrenchingly terrified because it was so violent…

BW: It’s quite interesting, the split opinions on race showing there and in other ways in the book.

SG: I think that that was really normal in a lot of families. Dad’s watching the match because the rugby’s on. You know; sport and politics don’t mix!

When I was writing Nine Girls, it felt like the 70s and 80s were an era that needed to be identified as a time of huge transition and realisation. Instead of looking outwardly at how terrible a lot of the racism and social structures in the world were at that time, we actually had our own problems here. We were finding them out through talking about other countries’ problems. By the time the book came out, I felt like we were going back to the 70s and 80s! That was really disturbing and upsetting. I really wished that the time for this book was not now, but I feel like the time for this book is now.

I really wished that the time for this book was not now, but I feel like the time for this book is now.

BW: Which is another reason why I think it’s such an important book. I also absolutely loved how you gave your acceptance speech in full te reo Māori. It sounds like you’ve been on an immense journey to get to that stage; full immersion for four years. Could you tell me a little bit more about that?

SG: I think it’s probably coming to terms with what I lost, because my mum died, and it’s probably taken me a while to circle the wagons around and realise ‘you can handle this now’. She’d taken me on a noho marae not long before she died. I can remember being in the wharenui with all these women and not understanding a word of what was being said other than ‘ka pai’, but still feeling this incredible sense that I was somewhere important and somewhere I belonged. I think she was feeling that too. Had she been alive still I think my transition into my reconnection would have been an easier thing, but that connection was severed.

My dad is Pākehā, but he’s certainly in no way the dad in the book. I tried to make the father in Nine Girls the sole voice for racism and intolerance because I felt like that was digestible for people. But in truth, all sorts of people said things like that all the time, he was not a lonely voice. Maybe they don’t say them so much in the lives we live now and the people I associate with don’t because my tolerance of microaggressions has gone down the gurgler lately! I tried to make the dad the repository of all the hatred and bigotry and the terrible backwards thinking. That’s the role he fulfills in the book.

I certainly feel like if my mum had been alive, I would have probably made the move a lot earlier and it would have been a lot less arduous. But it is what it is, right? Every time you go to a noho marae or you’re in a te reo class, it is profound. The amount of sobbing that happens on a noho marae is fairly indicative of how much of an emotional upheaval it is for people to realise they’ve been colonised—or struggle with the guilt that their ancestors were colonisers.

It’s owning trauma really. And there are a lot of traumas out there. Hopefully the book makes trauma a bit less traumatic and more identifiable for children.

…my tolerance of microaggressions has gone down the gurgler lately!

BW: If you could tell yourself anything back then, in your childhood, what would you tell yourself?

SG: Oh, first thing I would tell myself is stop studying French and go and study Māori! Yeah, absolutely. Although I have just been in Paris and I am able to order a coffee and a baguette, but everyone speaks English! What’s the point?

But seriously, I’ve got a really good school friend from Ngāruawāhia High School who in many ways is Tania in the book. We would spend all our lunch times together discussing the entire plot of the Black Stallion and things like that. She feels the same way as I felt, that we couldn’t own our Taha Māori at that point, that we weren’t Māori enough to be in the Māori studies class. I remember being curious and wanting to maybe take the language, wanting to join kapa haka, but feeling like I just wouldn’t belong because I was from the wrong side of the river. So, I just didn’t go there. We both feel like we shouldn’t be here now in this position having to reclaim what we should have had all this time. But it is what it is, and it’s never too late.

…we weren’t Māori enough to be in the Māori studies class.

BW: What do you hope for tamariki today?

SG: I think that the language is the access point. When you look at the way people are colonised, first of all, you take away their land. That’s something that really comes through in Nine Girls—I did not realise just how affluent and thriving the Waikato Māori were before the raupatu [confiscation], before the Tainui wars, before Governor Grey basically made a venal land grab driven by Auckland property speculators and settlers wanting a piece of what Māori had. It was not to do with the treaty. It was just a seizure of property, and it was never returned. What we had returned to us, because my tupuna was a loyalist, a Māori who took the side of Governor Grey and not the side of King Tāwhiao, was a really rubbish piece of land next to Taupiri Mountain. That’s where my grandmother grew up. It wasn’t our original land. It was tapu land that the Pākehā were too scared to settle because it was full of ghosts. It was scraps off the table.

Once you get your land taken off you, the next thing they take is language. When I was doing the book tour prior to the book awards, I would stand up in front of a group of kids and say, ‘All right, I’m going to do a karakia, and you’re going to waiata back’. And the kids are right there with you. They all know their pepeha. They can all mihi. They all have a good base level of being able to speak te reo Māori. Ideally, I would like to see te reo becoming stronger and stronger. And it should be everyone. This is a unifying thing. If we want to keep the language alive, it’s not enough just for Māori to speak it, it has to be Pākehā too.

…it’s not enough just for Māori to speak it, it has to be Pākehā too.

BW: I totally agree. I see that a lot as well in schools. The other thing I see more is storytelling, which is meant to be an integral part of the new curriculum. I love that storytelling and pūrākau [legends] are now being acknowledged more. What does storytelling mean to you?

SG: I think that was something I wanted to explore from the start of the book. At the start of the book, I say I was six when my goat went to work for Santa, which is, of course, a true story. My parents did tell me that my goat had gone to work for Santa. Not a true story in that my goat hadn’t actually gone to work for Santa. I don’t think my parents ever thought about my tenacity and my not being willing to let stuff go. So, three years later, I’m like, ‘where’s my goat?, where’s my goat?’, until mum finally cracked and said, ‘for God’s sake, we threw it over a farmer’s fence. We didn’t want to have a goat anymore!’ So, I suppose when I look back, there’s definitely a thick vein of fantastical, amuse-the-kids-on-a-dark-winter’s-night sort of stories that runs in my family.

I never thought of that as creating fiction, but I think it is kind of what they did. They loved to chat, endless cups of tea for hours and hours, and me thinking ‘God, these people can talk. When are we leaving?’. So, I suppose it was always there.

…my goat hadn’t actually gone to work for Santa.

I think possibly all the work I’ve done before, as a fiction writer, learning about structure, character, and how to keep the story moving came from there in some way. With Nine Girls, I was trying to do so much that I really worried sometimes that I wasn’t going to get through it.

BW: I think storytelling is so vital. I once read that story is part of the reason why human beings have survived for so long, because we were storytellers. We told stories to help people survive.

SG: I feel like at the moment, the arts are being treated like a ‘nice to have’. I think the arts are vital to who we are as humans and that telling stories and feeding our national conscience with our own stories of who we are as New Zealanders is vital; that if we can’t continue to do that, we’re starving again.

BW: And this is a fantastic book for that reason. I also loved how you handled Tania’s story so well. It’s a tough topic for young people to deal with. Did Tania’s story come from anywhere in particular?

SG: Yeah, she came from a few directions. One was the ritual of tangi, which I believe is so important to comprehending whakaaro Māori [Māori thought]. I felt like I really wanted to have that. That would be the way to get Titch back to her marae at last. I also had a friend at high school, at King’s College, not at Ngāruawāhia, who was very similar to Tania. I felt like the light of the sun shone out of them. They were so incredible. People who you think are destined to be for greatness can be lost. Then it’s up to you to step up and be what they could have been, as much as you can.

The book is dedicated to my friend Claire, who was a really well-known New Zealand hematologist who died of cancer in the time that I was writing the book. She helped me with all the research on leukemia. We would sit there together as she was dying, and she would say, ‘does this have to happen?’. Not to her, but to Tania. I said, ‘yeah, it does. I’m sorry. That’s the plan. That’s how life happens’. I wanted to take Titch and Tania on that journey together, of friendship being above and beyond.

BW: You handled it so beautifully and it was a lovely chance to accept that happening, which I really appreciated. But let’s move on to more positive things. This is the first time you’ve won the big one at the New Zealand Book Awards for Children and Young Adults. How does it feel?

SG: It felt on the night, and it still feels, that the book had its own trajectory. I’m really happy for Nine Girls. It feels kind of separate from me. I don’t know how to explain that. So, it’s fulfilled its destiny and I’m really happy for the book. I feel like I can carry on now with a different destiny for myself.

BW: Do you have any plans for new books? Are you going to return to ponies?

SG: No more ponies. For me, no more ponies. When I get complaints from mums of little girls, I can send them to my back list—it’s enormous. It’ll get them through most of their adolescence!

For me, no more ponies.

I have just written a new book, called The Last Journey, which will be out in July 2025. I came up with this idea when our house had just been flooded in the big flood in Auckland. We had to move out because our house had been pretty much destroyed. So, we moved to a place around the corner in a little cul de sac that was filled with cats.

I’d sit at my desk during the day and watch all this cat action in the street. The dynamic was really fascinating. My cat at that point was just a kitten, but Pusskin’s always been a bit of the George Clooney of cats. He’s just really charming and lovable. All the other cats were like, ‘Oh, Pusskin, we want to be your best friend’. I started imagining a sort of cat story that became a sort of a cat dystopia. So, yeah, it’s a very different book to Nine Girls.

BW: Is it told from the cat’s perspective?

SG: Yeah. It’s an epic adventure. It’s kind of like you crossed Logan’s Run with Watership Down, but with cats. I kind of thought after Nine Girls, I can’t write anything that big again. But I feel like The Last Journey is big in a different way.

BW: And did you ever get another goat?

SG: Yeah, we did get another goat. A slightly less cheery story. We named him Denver after John Denver, who was big at the time. The goat looked like John Denver. He was sort of pale and insipid, and he became a beloved family pet, until we came home one day, and my dog was lying between the goat’s head and the goat’s body covered in blood. It had ripped it to bits. I’ve got to say, not many of my pet stories end very well. Not a story that I share with the kids when I go on school tours!

BW: I find kids quite like a bit of gore!

SG: They do like it when I tell them that I had a pig and my parents had it butchered and we ate it for Christmas. They told me she’d just gone to live on another farm. So, endless lies!

BW: They’re not liars, they’re storytellers! It’s different.

SG: Yeah, I’m trying to reconcile myself with the fact that they are terrible liars.

Belinda Whyte

Belinda Whyte is the Resource Teacher of Literacy for the Horowhenua region, based in Levin. She is passionate about helping students to love literacy and enabling them access to good books and effective instruction. As a judge of the 2024 New Zealand Children and Young Adult’s BookAwards, she relished being able to indulge in her love of books and reading.