Story Hemi-Morehouse (of Ngāti Koata and Ngāti Toa Rangatira descent) is an award-winning writer-illustrator who burst onto the NZ literary scene after experimenting with her art during the Covid-19 lockdowns. With nine books already to her name, and more on the way, Story is quickly becoming a household name. Here, she chats with Nida Fiazi about her creative journey and marvellous mahi.

Nida: You were born in Tāmaki Makaurau, Aotearoa but migrated to Australia as a young’un. Did that move affect your art in any way?

Story: Haa, that’s a big question. There were certainly a lot of ways that move affected my life, but its effect on my art is most obvious now that I’m an adult.

During Covid-19, when visiting home wasn’t an option, I realised how disconnected many areas of my life had become. I was really thrilled to realise this during a period when I had a lot of free time to fix the problem, and so in an effort to reconnect with myself and others, I started drawing my ancestors. Their stories and faces reminded me of home and this process was a way for me to learn about my culture despite being separated from it. If I had to draw it, I was forced to become fully absorbed in its meaning…and so that’s what I did!

And although I am physically disconnected from the land, I still remember (so clearly!) the colours of the sky and the land, and how even things like the temperature and weather can affect the beautiful colour palette of home. It is much easier to channel those memories, rather than use what’s around me as inspiration, because anything I draw from that special time in my life instantly feels magical and special! It’s a treasured way for me to remember the world my younger self grew up in.

It’s not always easy to show people that I’m not ‘half’ this or that, but rather that I’m fully Māori and fully Pākehā—a complete whole. My art style became a way of asserting that to myself and others

N: Your characters have so much life and personality, and the way you balance colour and depict light is absolutely captivating. What/who has had the biggest influence on your art?

S: Bless, that’s so sweet to hear! I was obsessed with cartoons and superheroes growing up and I still am. The biggest influences were definitely Ninja Turtles, Power Rangers, Adventure Time and Steven Universe (the last two were especially influential in regards to my storytelling style and colour palette). I’m also a huge fan of the art style of graphic novelist Loïc Locatelli-Kournwsky, and I follow a bunch of animators who I learn a lot from.

N: Who do you create for?

S: Selfishly I think it started as something just for me.

I’m biracial—both my parents are Māori and Pākehā. I feel lucky to have that balance, but it’s not always easy to show people that I’m not ‘half’ this or that, but rather that I’m fully Māori and fully Pākehā—a complete whole. My art style became a way of asserting that to myself and others.

So though my art style may be more Western and cartoon-y, I’m lending that to my Māori side and saying ‘here, our stories aren’t so different after all, and we can be the main characters too.’ It was a bit of an experiment to draw Māori in that way over how we’re traditionally depicted, but it sprung from a genuine place—from the hope that the distance between my two cultures can be bridged through my art.

So at the end of the day I create for myself, but I still value my audience’s opinion and the impact it might have on them, very highly. After seeing how the books have been received, I am so motivated to continue this work for all the tamariki who get to see themselves in a way I wish I could have at their age. There’s certainly also an element of wishing future generations will treasure this as well.

N: You’ve illustrated three books (six including their te reo Māori versions) with Huia now, how did you come to work together?

S: It felt like a fluke—a really beautiful fluke. During Covid-19 lockdowns, I drew a couple of experimental characters of my tīpuna for fun because I wanted to learn about them. I posted them mindlessly on Instagram and got an email a couple of weeks later from Huia asking if I’d be interested in illustrating a book, and I was over the moon! We’ve been collaborating pretty happily since then.

N: You’re not just an illustrator, you’ve also written stories with your iwi about your tīpuna. What have you found to be the most challenging part of creating both the visual and written aspects of a story?

S: I have, yes. Working with my iwi was so, so special, because I got to tell the stories of two of my tīpuna. Writing and illustrating these books really felt like creating taonga—but man, there’s a lot of responsibility in that. The hardest part is making sure you have all the right research, and that everyone’s korero is respected in your writing.

It can also be a challenge balancing the reality and truth of these stories with kid-friendly visuals, or to place them in a slightly ‘magical’ stylized world without making them feel like a ‘fairytale.’ So the style and approach are super important too.

The biggest difference in illustrating Māori stories and characters is the perspective and the worldview. We ‘see’ ourselves and the land differently than Western cultures do. So everything, from the strength evoked from your characters’ poses, to giving the environment a real personality and place in the story, must be shown. It’s subtle, but essential, and I think it makes all the difference.

Working with my iwi was so, so special, because I got to tell the stories of two of my tīpuna

N: Māori stories have traditionally been (for the most part) passed down orally, so how does it feel and what does it mean to record and tell these stories in a physical form?

S: I’ll be honest, it feels like a lot of responsibility. Taking something that’s previously been preciously shared between trusted whānau members and solidifying or freezing those words and meanings in any way matters a lot. It’s a big honour to be asked to turn a korero into a storybook, so if you’re going to do it, you have to take direction well and prioritize the collaborative relationship with the iwi.

N: Most of your published works are Māori-Indigenous tales, was this an intentional decision?

S: I actually can’t believe that my body of work has turned out like this, because it was always a dream. When I was a teenager figuring out what I wanted to do, I thought about how special it would be to create animated or illustrated Māori characters and stories. I didn’t think they all had to be based in Aotearoa or be super traditional at all, I just wanted to be able to see myself more in the characters I loved.

I really wanted to be a part of visualising that in a modern way—it was just where my interests lay. But the world around me at the time told me that getting other people interested in that might be an uphill battle.

I was pretty happy at the thought of ending up in some animation studio somewhere, or illustrating any picture book—that would’ve been enough. But to be known for my depiction of Māori and our worldview really blows it out of the water for me—especially because everytime I make something, I’m learning something new on the spot.

I’m so thankful to be given the time and opportunity to learn about myself and my culture, and then share that with others. I’m absolutely open to work on anything so long as there’s a personal interest in the project, but the cultural space I’m in now is really special. Thank you universe!

N: Can you talk me through your research process?

S: Pinterest and Google are my besties. It’s part looking for facts, and part looking for vibes.

N: How do you decide when an illustration is done? Do you often have to resist the temptation to polish?

S: It’s done when I’m obsessed with it. When I look at it and I’m in love with it, then I can put the pen down. I often lose to the temptation to polish, because the finishing touches are my favourite part! I love adding highlights, atmospheric touches, and moody lighting to bring emotion to the world.

I end up going back three or four times to an illustration throughout the final colouring process, making sure every page is as magical as the last, as well as the next. The ‘flow’ of all the pages together is really important to me, so I refine them until they all look right together, and it’s something I can show really proudly.

N: You primarily create digital art, what is your favourite and least favourite part of the illustration process with this particular medium?

S: It took me so long to be confident with digital art, oh my gosh. It’s really hard going from traditional art to digital, so my least favourite part was all the years of trial and error—my poor uni teachers had to encourage me through a lot of bad attempts. I tried so many programs, and wrestled with a lot of different brushes to get to my current workflow.

But now it’s awesome and I can create stuff really seamlessly. I work with a 12.9-inch iPad Pro and use a software called Procreate religiously. My favourite part is the control and speed digital art gives you—it’s such a great tool. Embarrassingly, digital art is such a habit now that sometimes I draw on real paper and ‘double tap’ the page to ‘undo’ my mistakes…I rely on it that heavily.

N: What are you working on currently?

S: Aha, I’m not sure if I’m able to say that about my professional projects at the moment! But personally, I am getting really amped up to create a graphic novel this year. A lot of what I make never gets seen, so I’m trying to change that. It might be a slow process, but it’s something that brings me meaning. It’s just meant to be.

Even though I love working on children’s picture books, creating comics and graphic novels for rangatahi (young people) is actually where my heart lies, so I’m pining to do more of that. I also just love the control you have as a storyteller, writing, illustrating and self-directing like that! I’m hoping to tell even more personal stories moving forward.

Essentially, I’m just trying to ensure I continue creating authentically and with a lot of love in my heart. I would like to be an artist who can be inspired to go wherever I want to with my work, without pigeonholing myself into being known for one thing.

I would like to be an artist who can be inspired to go wherever I want to with my work, without pigeonholing myself into being known for one thing

N: You graduated from Griffith University at Queensland College of Art with a Bachelors in Animation, do you foresee yourself expanding into that medium in the future?

S: Ab-so-lute-ly! Can you imagine? Oh my gosh…I can. I have worked a little in animation and other creative fields before, but I dashed away to work in illustration because I wanted to tell my own stories. I would jump back into animation in a heartbeat if I got to design and direct in a similar way. I also just think the beauty of Aotearoa is screaming to be animated.

I’m not sure what the context would be, but yes. Yes, yes, yes.

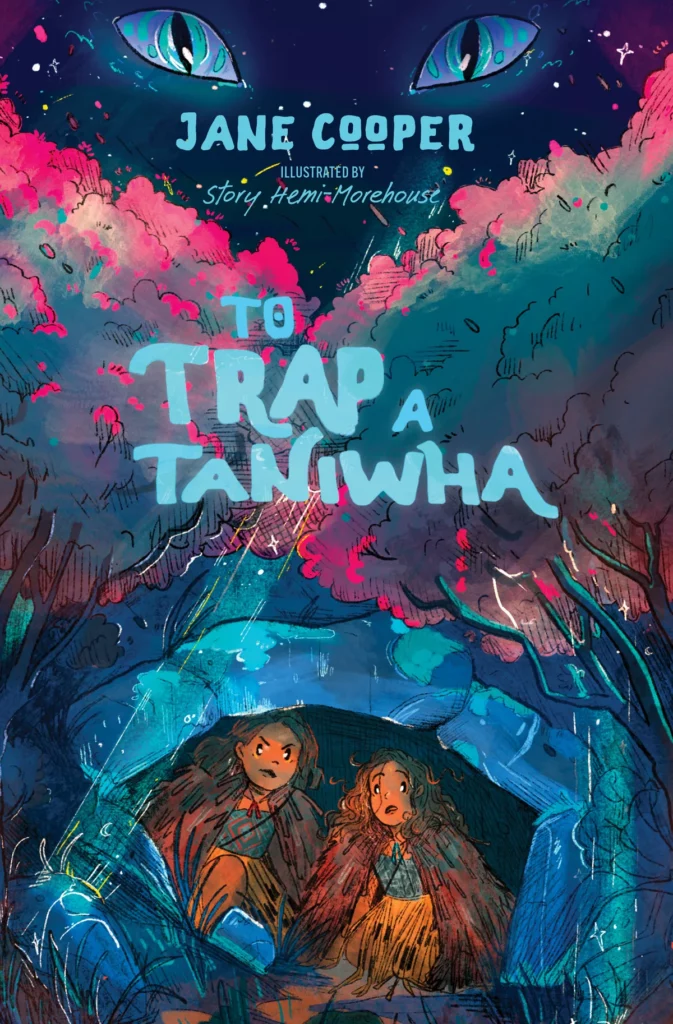

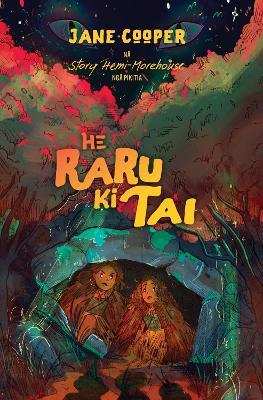

To Trap a Taniwha

Written by Jane Cooper

Illustrated by Story Hemi-Morehouse

Published by Huia

RRP: $25

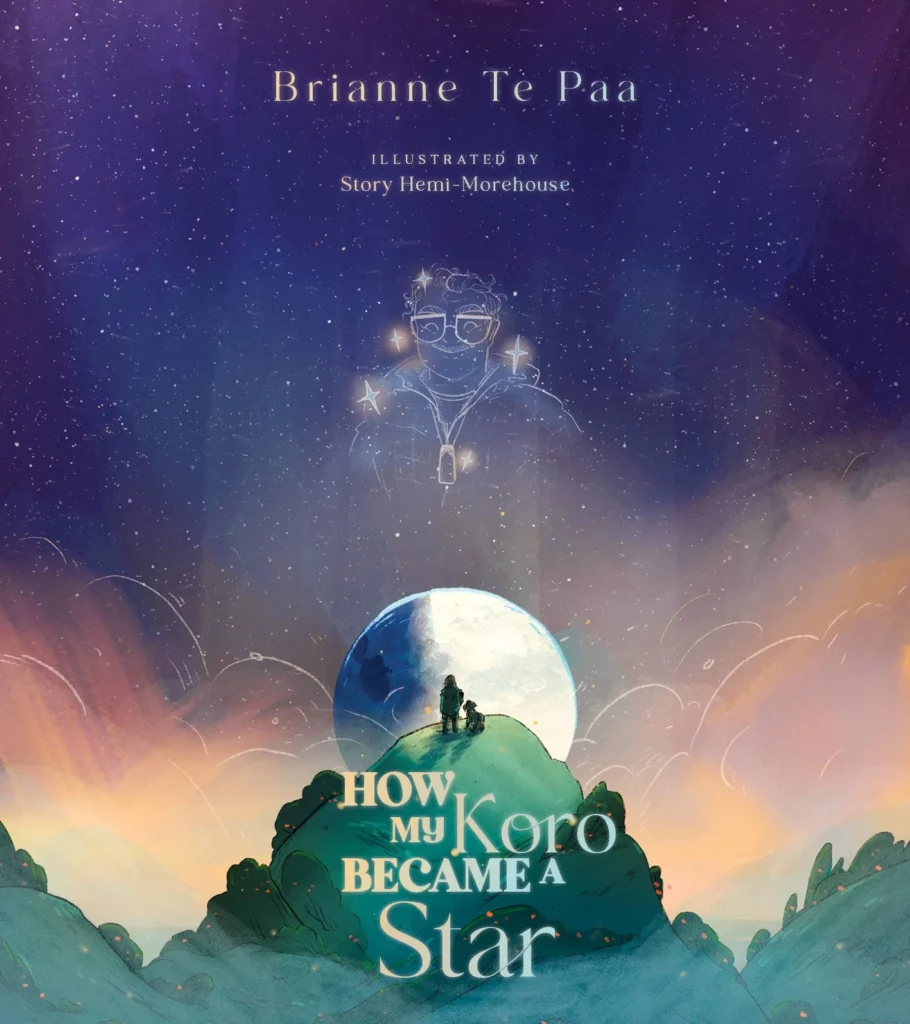

How my Koro Became A Star

Written by Brianne Te Paa

Illustrated by Story Hemi-Morehouse

Published by Huia

RRP: $22

Kua Whetūrangitia a Koro

Nā Brianne Te Paa

Nā Story Hemi-Morehouse ngā pikitia

Huia

RRP: $22

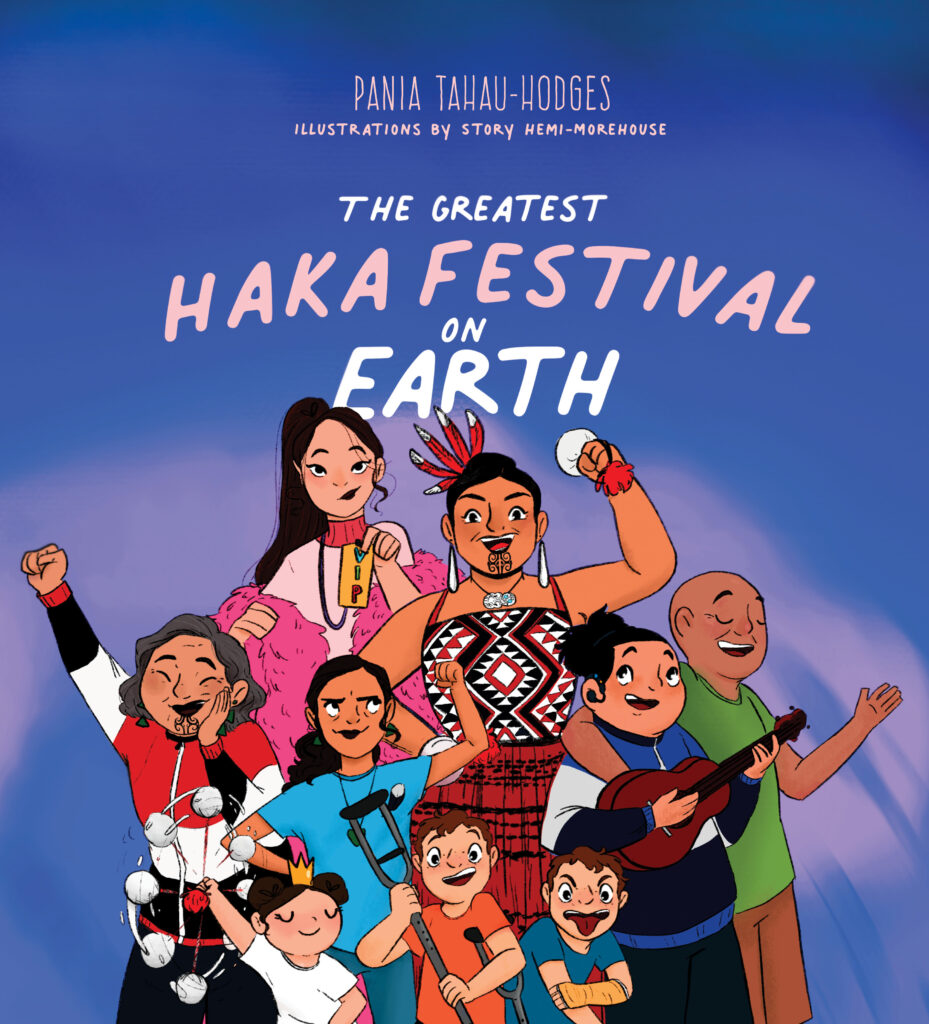

The Greatest Haka Festival on Earth

By Pania Tahau-Hodges and Story Hemi-Morehouse

Published by Huia

RRP: $22

Follow Story on Instagram: @storyhm_art

Nida Fiazi has worked in the New Zealand book industry for the past five years as a poet, editor, reviewer, and advocate for better representation in literature. She is a Hazara Kiwi Muslim and a former refugee based in Kirikiriroa. Her work has appeared in Issue 6 of Mayhem Literary Journal, the anthology Ko Aotearoa Tātou | We Are New Zealand, and Poetry NZ Yearbook 2021. She is currently penning an opera with Tracey Slaughter.