A conversation with Moira Wairama and Margaret Tolland

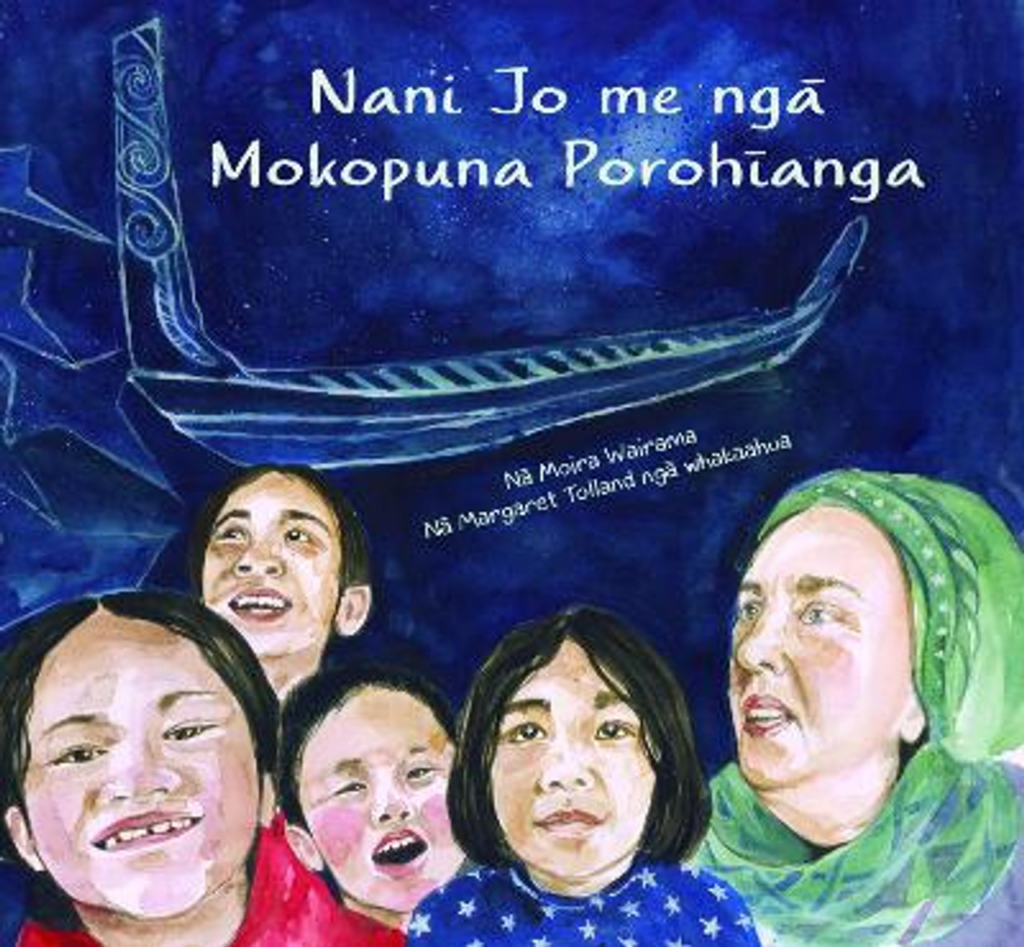

Bee Trudgeon has a heartfelt and heartwarming kōrero with Moira Wairama and Margaret Tolland about the creation of their new book, Nani Jo me ngā Mokopuna Porohīanga—Nanny Jo and the Wild Mokopuna, and the beautiful story behind it.

Once upon a time, there were four sisters, and all their children called them the Nannies. There was Nanny Moi, Nanny Jo, Nanny Sue, and Nanny Vicki. Nanny Jo felt she’d lived a good life, full of travel, love and adventures. One day Jo received a cancer diagnosis—her second—and knew her life was nearing its end.

Although at peace with the life she had lived, she told Nanny Moi: ‘I’ll just be sad that I’m not gonna be there for my mokos, that I won’t see them grow up…and for my sons too.’

Nanny Moi, known to most as Moira Wairama and as one of Aotearoa’s finest storytellers, said to Nanny Jo: ‘Could I write a book?’ She had always wanted to write down the story of Taramainuku, the celestial navigator who can be spotted during Matariki, sailing souls home. She wanted to catch Jo’s story in his net.

Nanny Moi, known to most as Moira Wairama and as one of Aotearoa’s finest storytellers, said to Nanny Jo: ‘Could I write a book?’

Upon Jo’s approval, a warm and tight collective formed to create the book which would become Nani Jo me ngā Mokopuna Porohīanga — Nanny Jo and the Wild Mokopuna. The team included publisher Baggage Books (Tony Hopkins and Moira Wairama), consultant Ruth McIntyre (founder and former co-owner, with her late husband John, of the legendary Wellington Children’s Bookshop), Japan-based designer Jess Hubbard, and illustrator Margaret Tolland (Fantail’s Quilt, Watch Out, Snail!, Go, Green Gecko!). They sought Jo’s blessing every step of the way, with courageous decisions made by all involved regarding both the execution and the editing of the artwork and design. Jo was present at two of the book’s launches in Porirua, presenting copies of the books to the child models, bringing to life the unions from the book’s illustrations, moment after moment.

It’s not often one gets to walk into a living aspect of a picture book, but that is exactly how I feel when I meet Moira and Margaret at Porirua East School, where the younger models for the book are students. There’s a transformed classroom, filled with the pieces of a collaborative mural Margaret is working on with ngā tamariki; a sign hanging in the window claiming the space as ‘Margaret’s Temporary Art Studio.’ When it comes to involving ngā tamariki in her creative process, registered teacher Margaret could not be more invested.

A recording of one of my conversations with Moira and Margaret is frequently punctuated by a loud pounding—Moira’s fist on the table—punctuating her passionate remarks about the state of children’s literature (and the limited opportunities offered to authors wanting to address it) in Aotearoa. In the past, Moira struggled, both ingeniously and triumphantly, to keep her essential book Ngā Taniwha i te Whanga-nui-a-Tara —The Two Taniwha of Wellington Harbour in print. Moira recalls the pain of being told no one would want to read books about taniwha, or that no one outside of Wellington would care about the story.

‘When you’ve got people like that running the industry, then you’ve shut all the doors off,’ she says.

When it comes to involving ngā tamariki in her creative process, registered teacher Margaret could not be more invested

Margaret agrees, and although she was more familiar with drawing flora and fauna than humans, saw this book as a chance to address some of Moira’s concerns.

‘I’m very okay with talking to the kids about how there are too many Pākehā images in books,’ Margaret says. ‘For me, in any artwork, in any kind of book, I want the kids to be able to see themselves. I think that’s huge because there are so many books where there are Pākehā kids all the time. The kids [at school] today were really excited, we were talking about “The Little Mermaid”, and they said, “The mermaid’s brown.” I said, “It’s really cool for you to be able to see yourselves.”’

Margaret says that when a child sees themself in a book, they can think, ‘“I’m allowed to exist in my world, I am safe, and I’ve got a place.” She adds, ‘It’s so horrible to see kids with low self-esteem because there’s nothing affirming who they are and their identity; I hate it. What they look like, what they speak, what they eat, what their family does…It’s gotta be there.’

Her chosen first language for the book is another way Moira authentically places her characters in their environment. ‘I don’t translate my books, I write them in Māori,’ she says. ‘I have a kaupapa that, if I can, I’ll write in both languages [te reo Māori and English], because some translations don’t really work, so it’s better to tell the story again, the same story. It’s a good challenge for me to write in te reo Māori, and I want to really keep doing that.’

[Margaret] adds, ‘It’s so horrible to see kids with low self-esteem because there’s nothing affirming who they are and their identity’

When Moira wanted to involve Nani Jo’s whānau in the artwork, Margaret immediately thought of combining collage with her own paintings. She painted a number of scenes and backdrops for master copies—‘basically, a stage setting,’ as she puts it—and then allowed whānau members to make something—ngā ika, ngā manu—cut out their creations and glue them on, rendering the illustrations an entirely collaborative affair. Margaret then photographed the artworks, and sent them, digitally, to designer Jess Hubbard.

Margaret thinks the book has three styles of artwork: the collages, the earthly illustrations, and the cosmologically magical paintings. We discuss the story’s transitions, from noa to tapu, and—in the final illustration of the family kuri, wrapped in Jo’s precious headscarf—to noa again. The book takes one on a spiritual journey that can be read in any number of ways.

As the book closes, the story of Taramainuku in the sky is bracketed as it began, with earthly scenes of the wild mokopuna and Koro, now planting a nīkau tree for Nanny Jo, and saying a karakia to Te Waonui a Tāne and all the creatures who live in the ngāhere. When Koro shows the wild mokopuna how to find the stars of Matariki and Tautoru, so they will know where Taramainuku is sailing his celestial waka, he sadly tells ngā tamariki, “Soon Nanny Jo will climb into the net of Taramainuku.”

Margaret thinks the book has three styles of artwork: the collages, the earthly illustrations, and the cosmologically magical paintings

Although it did not make the final edit of the book, Margaret did create a picture of Jo, resting, with whānau gathered around her bed.

‘That was a really precious painting for me to do, even though it’s not used in the book. It’s one of my favourites. It captures something.’

The painting clearly informs the character development, and treads lightly in the tender, reality-based world the book inhabits.

‘And look how brave that is,’ Moira points out, regarding the omission of the painting, ‘to let us not put it in. I think it was a good call, because, when you look at a lot of books that are written [about death], they have everyone gathered around the bed, and so, by not [including that depiction], she’s just freed it to be any way. But it is a lovely photo…’ She corrects herself, ‘A lovely painting.’

The line between art and reality is very blurry in this area. We touch on the inherent energy in rendering a person in a state they have not yet reached.

Margaret, who was also drawing on the loss of her aunt and her parents, said the moe scene was hard to paint. For Margaret, working with Jo’s story was, in some ways ‘too close’ to her own losses. ‘But then, I think it was probably quite a good thing for me to do,’ she says.

When she painted the eventually omitted scene—which was shown at the book’s launches—Margaret says, ‘I just thought, “She’s asleep. She’s not dead.” Because she’s still alive, and I want her to be asleep. She’s having a moe, and there’s love around her. I felt quite pleased about that, because I was really aware of that.’

The book has become a very special part of the lives of its contributors, providing a helpful and comforting way for many of them to talk about death. We talk about how one child reflected the book into their reality this way: ‘Pop, he climbed up, but then he turned into a bird, and he flew away.’

‘So,’ says Moira, ‘he’s taken the base of the story, he’s added his own explanation of why it’s different for his Pop. That’s the whole idea, I wanted kids to be free enough [to decide what they believe], and for parents to say to them, “Well, for us, we think this is what happens.” For people who believe in reincarnation…When I tell the story, I always say some people believe they come back and do it all again, and some people fly off to Heaven… What’s really interesting is that adults are talking to me about it.’

‘I think a good book, a good play, a good story—whether it’s a story told in pictures, or words, or whatever—should work for whatever age. It doesn’t matter if you’re an adult: if it’s a good story, it should hold you’

‘I think a good book, a good play, a good story—whether it’s a story told in pictures, or words, or whatever—should work for whatever age. It doesn’t matter if you’re an adult: if it’s a good story, it should hold you. If you’ve got a good story, I think people recognise where they fit, or how that story touches them. It’s not a sad book,’ says Moira. ‘It’s not a heavy book, but it’s a book that opens the door to the conversation.’

Part of that conversation—for Moira, at least—traces our origins to the stars. As she has written in the text: ‘Soon Nanny Jo will climb into the net of Taramainuku…’ For now, on Earth, the real Nani Jo’s last line remains unwritten; but, forever committed to the page, her story will continue to move those she sails beyond.

Kua whetūrangihia koe — you have now become a star.

Nani Jo me ngā Mokopuna Porohīanga

Written by Moira Wairama

Illustrated by Margaret Tolland

RRP: $25

Bee Trudgeon

Bee Trudgeon is a children’s librarian, writer, strummer, storyteller, dancer in the dark, film buff, perpetual student, and mother of two study buddies. Often spotted urban long-distance walking wearing headphones and a ukulele, she lives in a haunted house in Cannons Creek, and works in Porirua and wherever anyone will have her.