Patrick Ness, the revered author of the Chaos Walking trilogy, visited New Zealand last week for events at Verb Wellington and Auckland Writers Festival. Sarah Forster watched his Wellington events and spent thirty minutes having him sign her sizable collection of his books and asking some follow-up questions.

Demagogues, bullies, and dictators are not new to Patrick—he frequently uses them as characters in his bestselling YA books. Mayor Prentiss in the Chaos Walking trilogy, the mother dragon in Burn, even pelican Palicarnassus in his new middle-grade book Chronicles of a Lizard Nobody. It’s no surprise then that the first question at his hour-with session at Verb last Sunday was on Trump’s re-election.

Initially he deferred, joking ‘Thanks Kim’, for the difficult question (delivered by writer and Verb founder Claire Mabey, as programmed chair Kim Hill was unwell) before speaking eloquently about art and politics. His key message for all artists and creators is to keep creating in the face of bullies. When we sat down in the green room, I had to ask him to elaborate:

‘Let’s say that the election of Donald Trump causes you despair, which is not an irrational response at all. I get a little chippy about it, thinking, well, they want me to despair. Yes I’m going to feel bad about it because I think it’s a terrible decision for a lot of reasons, and it’s going to be not pleasant, but they would like that if I didn’t fight.

‘They would love it the best if I sat down. And so I’m not. I’m absolutely not. They’re not going to decide who I am.’

They would love it the best if I sat down. And so I’m not. I’m absolutely not.

This mixture of wisdom and quick humour characterised the two fantastic sessions I saw him in. Perhaps this is not surprising from someone who has won the Costa Children’s Book Award, the Guardian Children’s Fiction Prize, the Red House Book Award, the Jugendliteratur Preis, the UKLA Award, the Booktrust Teenage Prize and the two Carnegie Medals (‘in a row,’ as he interjected at his event on Sunday afternoon).

Red light reading, on the books children’s writers read before they perhaps should have, saw him wax lyrical about Daniel Pinkwater, who he praised for showing him that writing didn’t need to be polite or formal, Toni Morrison’s Beloved (‘like sitting at the grown ups table for the first time’) and quip, ‘It’s weird to be on a panel where you have to make your stance on incest clear: I’m against’ (in response to Lauren Keenan citing Flowers in the Attic). Then he shared vulnerability, writing tips and humane insights throughout his discussion with Claire Mabey.

This understanding of humanity is something I’ve always admired about Patrick’s work; his ability to create characters you can walk alongside and understand the motivations of—and this includes those who represent the worst of humanity.

‘The very best kids novels make space for you,’ said Patrick in his interview on RNZ a couple of weeks ago. When I sat down with him after his Sunday session, I asked him how he did this in his novels.

‘I am wondering who I am in it. My main character is always substantially me. So then I start asking questions of myself—I want my characters to be as real and relatable as possible. They need to make decisions that aren’t beyond a reader’s understanding. Everything your characters do has to feel logical and really human.

‘I get turned off from books when I don’t believe the decisions that people make. And that’s what I’m trying to avoid at all costs. I think that that’s the line where you rule a reader out if they cannot understand what your character does. There’s no place to live there.’

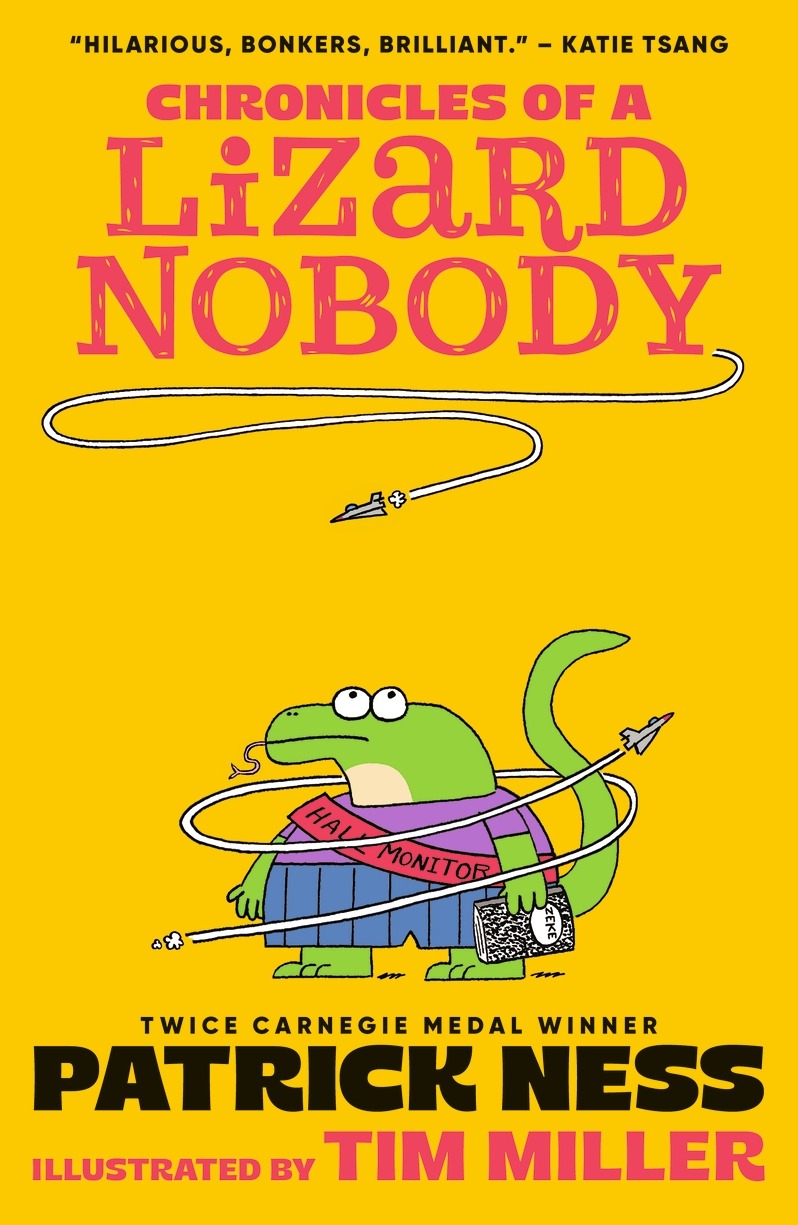

The surprising Chronicles of a Lizard Nobody

I was as surprised to read a middle-grade comedy from Patrick Ness as the author seemed to be about having written one. ‘It started with a pun—hall monitors and monitor lizards. I thought it couldn’t possibly be a book. But you never know when an idea is going to grow.’

The key characters in Chronicles of a Lizard Nobody are three monitor lizards, and a blind hawk called Miel, ‘IT’S FRENCH FOR HONEY’. (Miel speaks in all-caps because he can’t change the loudness of his voice. Because he’s a hawk). On introducing Miel, who takes the bus home and wears sunglasses, Patrick says, ‘I like the idea that they got to meet him and he got to meet them before any of these stereotypes and social pressures around what birds do and what lizards do got to them.

‘That can change things and that really makes me happy. He’s not a type of person. He’s a person.’

Zeke, our main monitor lizard, is a self-doubter. ‘And that way wisdom lies. Yeah. So, Zeke’s path to wisdom: the Tao of Zeke.’ Zeke frequently reflects on why he does things, and makes some very astute observations. Patrick elaborates; ‘I just think we believe what we’re told so much and so quickly. And when you’re young, why would you doubt what you’re told. Middle-grade is the age where you start to think, “Ohh, wait a minute. Is that actually right?”’

Zeke starts considering the stereotypes around the various animals at his school—including the one around monitor lizards, which he incidentally subverts himself by being much larger than most peach-throated monitor lizards:

Birds held themselves above most of the rest of the school, and yes, that was literal. They could fly, and they never let anyone else forget it. Well except for the emus and the ostriches, but they seemed more like bears anyway, if you asked Zeke. It’s not that there weren’t nice birds, but the worst bird was always worse than the worst lizard, Zeke thought.

Then he wondered if he thought that only because he was a lizard.

My main character is always substantially me.

Miel is a truth teller. He challenges Zeke to work out if he is ‘KIND OR WEAK? BRAVE OR PASSIVE? WISE OR AFRAID?’ And by the end of the book, Zeke is pretty much there. ‘POWER IS NOTHING EXCEPT WHAT YOU DO WITH IT!’

This is a lesson that the arrogant villain Pelicarnassus would do well to learn, as the quartet take him down while he drives his giant Pelican-robot suit, trying to destroy the school.

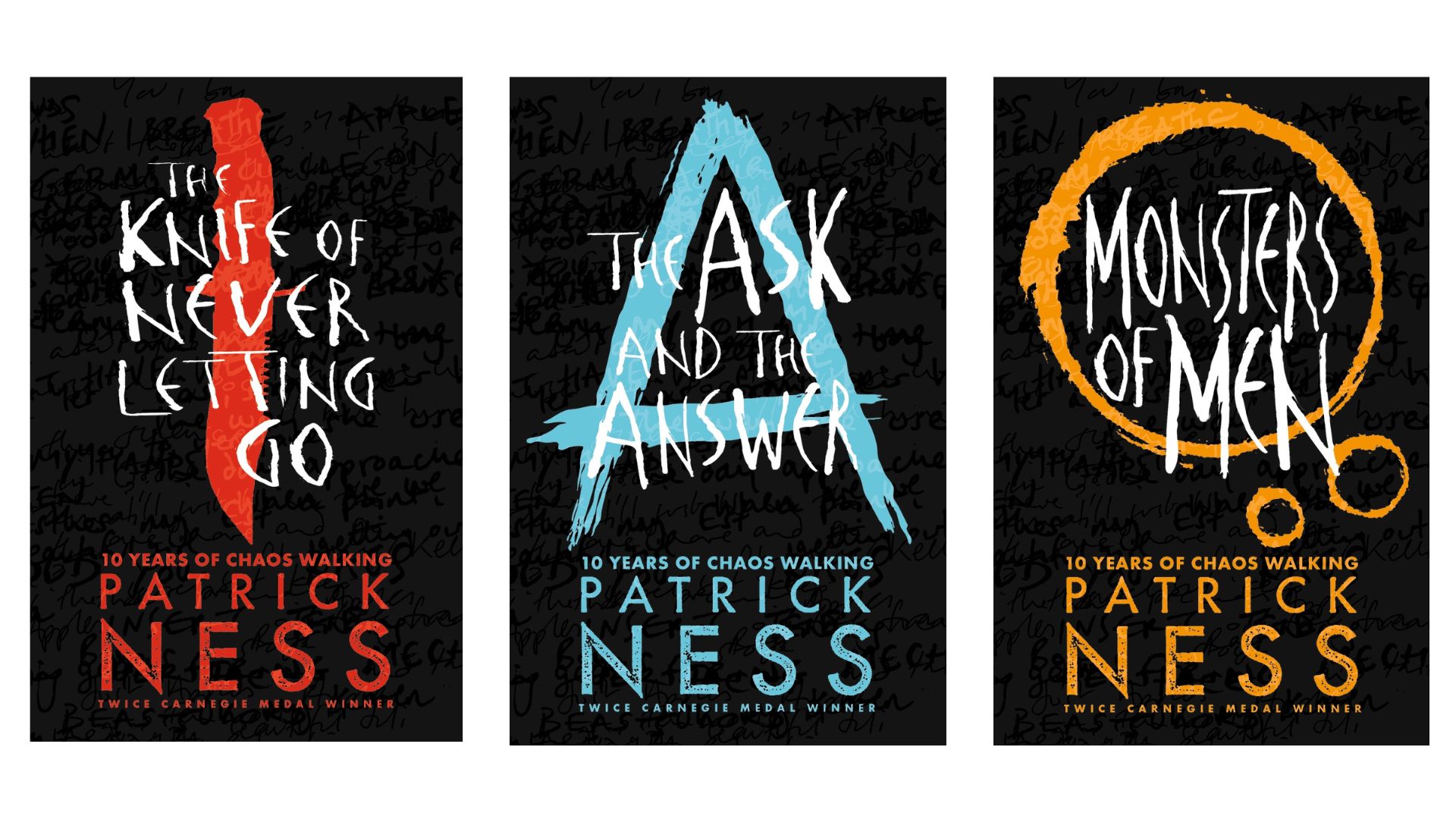

Chaos Walking and colonisation

The Chaos Walking trilogy is about the damage caused by colonisation to the colonised. It’s also about mind-blowing greed, misogyny, bigotry, how power perverts, and how love can prevail through it all. And how good is more powerful than evil.

Mayor Prentiss put me in mind of Trump, and made me ask whether Patrick ever wrote books in direct response to world events. He says not really, but explained Chaos Walking—where ‘Noise’ provides a constant, overwhelming stream of information—was in response to social media and the way that we moved away from privacy as a society. ‘But it wasn’t a particular event.’

‘I tend not to have an intentional response to something, but when I’m responding to a [news] story, I know that I’m responding to something for a reason and I have to trust that that reason is because it’s something I care about and that worries me, so it’s going to rise again obliquely. I write about things that I’m concerned about, but never specifically, almost never specifically.’

Chaos Walking is a three-part argument that recognises the damage done by colonisation and starts to work out how to resolve it. I asked him where this series began. ‘I’m from the West of America—my state is filled with native place names, and there’s native reservations (which we still call reservations—which is wild). And I had read a lot of Australian literature and what happened to their First Nations people.

‘So I thought well if we move to another planet, would we do the same? And my thought was probably yes. And so it was a direct expression of that—who are we really and what does colonisation cost the colonised and the coloniser. And is there a way to live together?

‘What I am really interested in is, “how do we do that?”. How do you live with your former oppressor, when you might still be using the language of this oppressor? And how do you do that where your life isn’t just a reaction to what they want you to be? And how do you hold on to who you are? And what does it cost if you are a member of the oppressor group? And you are trying to live in a different way, and trying to make a different future.

…you have to hope that the percentage of people figuring it out will win in the end.

‘That is a constant discussion all over the world, and sometimes we figure it out, and sometimes we don’t, and you have to hope that the percentage of people figuring it out will win in the end. But it sure doesn’t seem like it when people keep winning elections based on the language of oppression and division of oppressors. But it’s another reason not to give up.’

Toitū te Tiriti, indeed!

I asked him how he came up with the culture of the ‘Spackle’, the indigenous people of ‘New World’, which humans have invaded. ‘When I created the Spackle culture, I was deliberately trying to avoid any appropriation, so I specifically tried to make it as alien as possible. Because that’s how colonisers see the colonised anyway—we see them as alien, even if it’s not true. So then it becomes a question of where we can find common ground.’

Patrick questioned himself though—was he really good enough to create a culture out of whole cloth? ‘There will be things I’ve pulled into it. But I was trying to make it purely alien, but sympathetic and understandable. I wanted to make it so if there is the slightest effort toward connection, there is connection.’

A little about writing a book

When in discussion with Claire earlier in the afternoon, Patrick had pointed out that his success came pretty early in his career—he won two Pulitzers in a row, for Monsters of Men, the last book in the Chaos Walking trilogy in 2011, and for A Monster Calls in 2012—and that gave him freedom from the market.

This means he isn’t seeing what is trendy and writing to it, like some writers need to early in their careers—and that he can push the envelope, which is why each of his books seems so fresh.

On writing days, he sets himself a word-count goal, and then everything else waits until he completes it, because that’s his primary role. ‘I work on two projects at a time, that are at very different stages or across different media, so I can move from one thing to another and it feels like a refresh. I keep two different muscles at the same time.’

Both in his event, and in his discussion with me, Patrick often noted that he is not an expert on what works for everyone when writing—it’s just what works for him.

As he’s written trilogies and single books, I asked how he knew when a book was a trilogy in disguise. He says it’s gut instinct. ‘I sometimes realise it has separated into three ova—I see the shape of it, and how it will play out.’ And he keeps it all in his brain! ‘I just have word counts for each section, so I can see where it might be a little baggy.’

If you are a fan of Patrick’s work, you’ll be delighted to learn that there is another trilogy set in the same world as Chaos Walking to be released from 2026. And a second book about Zeke and his friends next year (‘Daniel starts wearing a hat and it causes a ruckus. But maybe not the ruckus you think’). I can’t wait.

Sarah Forster has worked in the New Zealand book industry for 15 years, in roles promoting Aotearoa’s best authors and books. She has a Diploma in Publishing from Whitireia Polytechnic, and a BA (Hons) in History and Philosophy from the University of Otago. She was born in Winton, grew up in Westport, and lives in Wellington. She was a judge of the New Zealand Book Awards for Children and Young Adults in 2017. Her day job is as a Senior Communications Advisor—Content for Te Herenga Waka—Victoria University of Wellington.