In our second instalment for NZSL Week, parent of a Deaf child and NZSL interpreter Jennie Yang goes through their tips on reading and storytelling with their child. See our first piece on storytelling in sign here.

We started our signing journey with B about six years ago. Initially doing a quick search online and stumbling on American Sign Language (ASL) videos before being introduced to New Zealand Sign Language (NZSL). It has been at times frustrating and scary, but mostly, it has been rewarding, fulfilling and joyful. NZSL has given our kid the ability to express themselves; to have deep and meaningful or funny and whimsical conversations. Our intention has always been for B to become bilingual, perhaps even multilingual, and NZSL has enabled us to enjoy books and encourage English literacy. Studies have consistently shown that Deaf adults who are fluent in both a sign language and a written/spoken language have better educational and employment outcomes than those who are monolingual. This study found that Deaf adults who were bilingual had higher educational attainment and higher incomes than those who were monolingual.

Along the way, we have found a number of things and been given tips that have worked well. Mind you, these tips need not only be strategies for reading with Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing (DHH) children but often can be beneficial for all children, including some who may have other reading challenges.

Here’s a summary of each tip:

1. Choose the right books, especially for younger readers

Look for books with clear illustrations, simple text, and engaging stories that are appropriate for your child’s age and interests. I personally love using book series with familiar characters in each book introducing different concepts. Examples of these series include Hairy Maclary by Lynley Dodd and Spot books by Eric Hill. There are also animated versions of these books online and they are a wonderful resource for DHH kids! Be sure to turn the captions on the videos no matter how young the kids are as exposure to printed words both in print and on-screen is an important first step in bilingualism.

2. Use visual aids

Visual aids can include props, pictures, and sign language to help your child understand and engage with the story. Research shows that DHH children differ from hearing children in visual-spatial processing, memory and executive function, which can impact their reading skills. Another study found that Deaf individuals have better peripheral vision and visual attention than hearing individuals, therefore, utilising visual aids encourages ease of maintaining focus and attention. Some of my favourite visual aids are flash cards and you can tailor-make simple ones using free sites such as Canva.

3. Watch for cues, especially eye-tracking and facial expressions

Pay attention to your child’s body language and facial expressions to ensure they are following the story and understanding the content. Here is an example of B having a conversation with a Deaf friend whilst incorporating flash cards. Notice how the Deaf friend gently taps B’s hand for attention and how they repeat B’s sign to reinforce and confirm that they have understood B’s meaning.

4. Use sign language

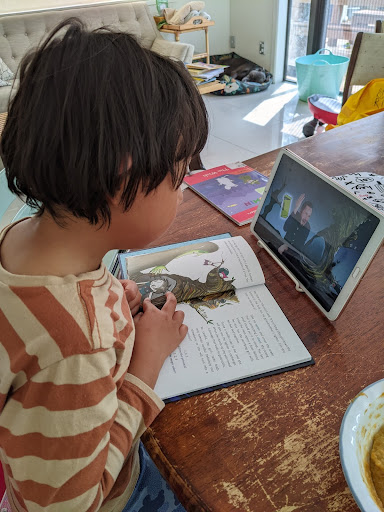

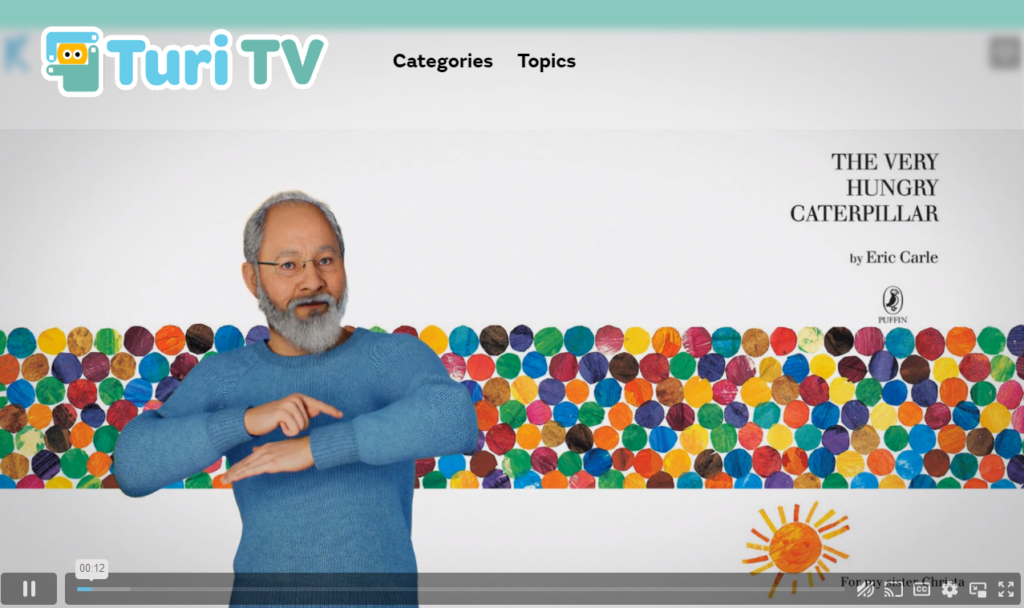

Don’t be afraid to use sign language, even if you are still learning as a parent. The NZSL dictionary can be a helpful tool for building your vocabulary. Remember you can gesture, point and act-it-out too! When we first started on this journey, we relied on external sources for fluent, translated versions of books. TuriTV is a web-based NZSL resource with signed books using both human signers and Avatars. One of B’s favourite books is The Very Hungry Caterpillar (available as a signed book on TuriTV) and the incredible lessons we’ve gained from this story are multifold. From the days of the week to different foods and the life cycle of a butterfly!

5. Provide context

Many Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing children do not have full access to incidental information and often miss out on context clues and inferences. Even a simple sentence like, “Mum will not be going to the shops again today.” infers that mum has been to the shops. For early readers, it helps to narrate the story. Make up the scenario so that it provides a fuller picture for the child. Deaf children are often exposed to reduced input and stimuli compared to hearing children. This is because spoken language is the primary means of communication in most cultures, and Deaf children may not have full access to spoken language or incidental information in their environment. In addition to reduced input, Deaf children may also be exposed to fewer social and cultural stimuli compared to hearing children. This can impact their social development and understanding of the world around them. Help your child understand the context of the story by narrating and adding details that may not be explicitly stated in the text.

6. Read, refer, repeat

Use real-life examples and experiences to reinforce learning and help your child apply what they have learned in the story to their everyday life. Reading the same book repeatedly is an effective strategy with DHH kids. With each reading, include the “lived experience” to make it interesting. Remind them of something they saw and incorporate that into the story. I try to stretch the reading experience by referring to our topics or subjects when on our walks. For example, when B was younger, they loved the “Opposite” book (part of the Hairy Maclary series) by Lynley Dodd. While on our daily walks, I would point out things that were opposites and this would absolutely delight B. Soon enough, B would start pointing out opposites themself. One such example that really stuck in my mind was while on a walk, it started to drizzle so we ran under a roof for shelter. Half of the concrete floor that we stood on was dry, and the other was wet. “Opposite mama!” pointed B excitedly!

7. Encourage participation

Parents can encourage their children to participate in the reading process by asking them questions about the story, pointing out interesting details in the pictures, or encouraging them to retell the story in their own words. This is particularly important with Deaf children for the development of Theory of Mind. Researchers have found that although hearing children develop Theory of Mind from as young as five, it is often much delayed in Deaf children. I love to explore “what ifs” with B. Questions that pose different scenarios are fun and encourage imagination, empathy and an understanding of emotional responses.

Another aspect of early literacy is the early exposure to English alphabets and fingerspelling.

8. Early and diverse exposure

In my opinion, this is an extremely important strategy to use with DHH kids, given their lack of accessibility to indirect and environmental interactions. Reading, as part of a larger strategy can facilitate a wider understanding of the world around them. Exposure to complex and diverse books that explore a wide array of societal and emotional behaviours can provide richer and varied language acquisition. Another aspect of early literacy is the early exposure to English alphabets and fingerspelling. It is never too early to start exposing your little reader to the alphabets and to start fingerspelling key words in books.

9. Use technology and online content

The use of closed captioning and speech-detection software can assist DHH kids in acquiring more vocabulary and gain a better grasp of English syntax and word order. A wonderful web series developed by the Ministry of Education in Queensland is Sally and Possum. The series is entirely in Auslan (Australian Sign Language) with spoken English dubbed over. There are also educator resources and an app that teaches English literacy and numeracy.

10. Be patient and have fun

Remember that reading should be a fun and enjoyable experience for both you and your child. Be patient and take the time to make reading a positive and engaging activity. I also recommend sharing the load! Engage a Deaf friend to share a book or retell a favourite story in fluent NZSL.

Sharing a book is as much about learning to read as it is about bonding and creating memories.

If you are interested in more in-depth research and recommendations, an excellent place to start would be Gallaudet University. The Gallaudet University Press has published a book called Reading and Writing in the Global Classroom: Stories of Compassion and Connection, which includes a chapter on “Reading with Deaf Children” written by Dr. Connie Mayer, a Professor of Education at the university.

In the chapter, Dr. Mayer provides recommendations for reading with Deaf children, including the importance of creating a literacy-rich environment, selecting appropriate books, incorporating visual and tactile materials, using sign language and other communication modes, and creating a collaborative reading experience. Dr. Mayer emphasises the importance of incorporating cultural and linguistic diversity into the reading experience and recognizing the unique strengths and challenges of Deaf children as readers.

Additionally, Gallaudet University’s Laurent Clerc National Deaf Education Center has developed 15 principles for reading to Deaf children. This is based on research of Deaf parents and how they read to their Deaf children. Do note that this is based on American Sign Language (ASL) but the principles can be applied to NZSL.

Sharing a book is as much about learning to read as it is about bonding and creating memories. Weaving NZSL into this experience can enhance both your learning experiences and give your child the access that they deserve!

1 Hrastinski, Iva, and Ronnie B. Wilbur. “Academic achievement of deaf and hard-of-hearing students in an ASL/English bilingual program.” Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education 21, no. 2 (2016): 156-170.

2 Marschark, Marc, and Harry Knoors. “Educating deaf children: Language, cognition, and learning.” Deafness & education international 14, no. 3 (2012): 136-160.

3 Codina, Charlotte, David Buckley, Michael Port, and Olivier Pascalis. “Deaf and hearing children: a comparison of peripheral vision development.” Developmental science 14, no. 4 (2011): 725-737.

4 Marschark, Marc, Vanessa Green, Gabrielle Hindmarsh, and Sue Walker. “Understanding theory of mind in children who are deaf.” The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines 41, no. 8 (2000): 1067-1073.