The announcement last week that the Year 7–13 English school curriculum is being rewritten by a select group of just five educators has drawn a strong response from the education and creative sectors. Following high school teacher Susan Briggs’s response, poet, playwright and essayist Renee Liang collected responses from six Aotearoa creatives, plus her own, to this move.

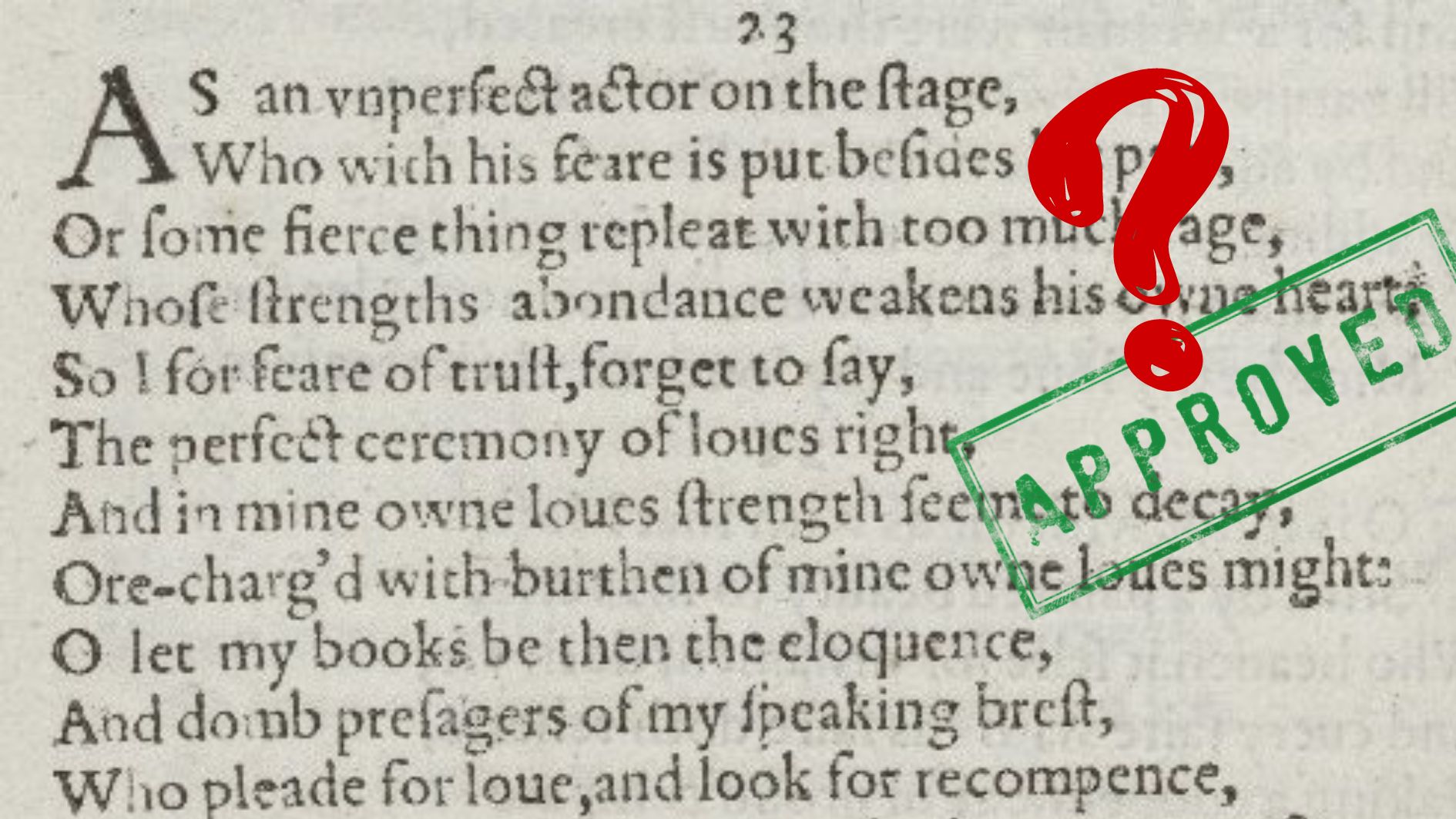

While press releases trumpet a revised curriculum featuring ‘compulsory Shakespeare for secondary school students’ along with a recommended list of books which heavily features writers from the Western canon (a few NZ books are also mentioned, the most recent of them published in 1982), concern has been raised that this seems to have been developed in secret and with little consultation with the teaching sector. Indeed, the language used to describe the proposed new curriculum—‘knowledge rich’, ‘literary qualities’, ‘the very best English language and literature’—smacks of European exceptionalism and a bias towards more ‘traditional’ texts.

Is this a good move that will grow our next generation of readers, writers and art makers? I asked six Aotearoa creatives across a range of ages, career stages and communities, to share what inspired them as students and how that has shaped their instincts as creative professionals now.

Albert Belz

STICK IT IN A MUSEUM WITH THE MODEL T

Can somebody suggest a really funny Shakespearean comedy? It’s a trick question, there are no funny comedies by Shakespeare, at least not anymore. Like vaudeville or Benny Hill, Shakespeare’s comedies are and should be a thing of the past. Set to rest in a BBC museum where they can at least be respected and admired for the genius they once were.

But hang on, if we just put it into context and explain how it was comedy genius back in the day, then readers and students of Shakespeare can appreciate his genius. Here’s the thing. The moment you must explain why a thing is funny—then it’s not funny anymore.

So why are we asking students of English to study the literary equivalent of a Model T? Especially when we have the roaring furnaces of Waititi’s sup’d up Mark 2 Zephyrs catching the eye of audiences worldwide.

But he was a genius at all dramatic levels! Shakespeare was the foundation of modern theatre or some-such. Agreed. But so was Henry Ford (love him or hate him) the foundation stone of mass production and the genius that was the Model T. But you won’t see anybody driving a Model T when you can drive a perfectly good Nissan Explorer let alone a Porsche 718. The Model T is far from irrelevant, but it is certainly unrelatable and indeed outdated by almost a hundred years and ANY modern standard.

So why are we asking students of English to study the literary equivalent of a Model T? Especially when we have the roaring furnaces of Waititi’s sup’d up Mark 2 Zephyrs catching the eye of audiences worldwide. Or the sleek mobiles of Sarkies, Kouka, Henderson, Grace-Smith, Hall et al. burning rubber on the mean streets of NZ’s modern literary circuit.

As a teacher myself, I can tell you one (slightly cynical, but relevant) reason: because we’re too damn busy to create new educational resources for our classes. Why don’t I just roll out the Model T which has a ton of educational resources that I don’t have to create myself, not to mention some theatre company parading the same ol’ that I can take my students to. Hell, I can even get them to come to me. More admin problems solved! SO, you probably won’t hear too many teachers complaining about churning out the same ol’. But my God! You will hear the students. ‘Cause no sane kid wants to imagine themselves in a Model T. And why would they?

Renee Liang

I admit, I was and still am an English nerd. From primary through to secondary school, and again as a postgraduate university student, I’ve been lucky to encounter teachers whose passion was wildly catching. When I think back, what all of those teachers had in common was that they recognised my hunger to read widely. My schoolbag became a Tardis whenever I entered the library, sucking in vast amounts of varied reading material ranging from life and love during the Prague Spring to Neanderthal cunnilingus (thank you, St Cuthbert’s librarians, for buying Clan of The Cave Bear which would end up forming the bulk of my sexual knowledge as a teen).

Literature is life, it is alive, and any curriculum needs to set teachers free to empower their students as they know best.

Whenever I jumped into my Tardis with my haul of books I was transported across time, space and realities, and to say it was transformative and identity-forming is an understatement. My teachers wisely understood that their role was to open the gates wider, not constrain them to narrow pathways. They also understood that every person was different in what they needed. Whenever I—as a NZ-born Chinese of colonised (Hong Kong) stock—tried to go for ‘just the classics’ they quietly turned me to look in other directions, and they radiated pride when subsequently I shared my own ‘finds’: Hone Tuwhare, Amy Tan, the Def Jam poets.

This has shaped me as a writer, I think. I’ve never been afraid to try something new—in fact I seek it out. I’m well set up to analyse why I like or don’t like a particular text—structure, function, pacing, theme, yada yada. Don’t get me wrong, pinning down why a text speaks to me on a technical level is important—I’m a reviewer and a dramaturg after all. But what’s more important is the magic of a text—magic that gets translated to performance, a picture in a reader’s head, the sudden pinch of emotion in the nostrils. For me as a writer, it’s also about taking risks. Literature is life, it is alive, and any curriculum needs to set teachers free to empower their students as they know best.

Sanjana Khusal

Neon post-its. Rainbow highlighters. HB pencil. Bic pens. I spent my lunches in the only computer lab the English department had. I spent my NCEA years with my feet propped against the gas heater, freezing with the fractured windows and cheap linoleum floors. The walls were decorated with poetry about WWII from Year 9 students who were probably in their 30s. I was filled with smug pride for finishing Brave New World while the class was barely halfway through the Youtube audiobook reading. Instead, I would be working on the next great novel—a Wattpad original, starring a mysterious biker, a white nerdy girlie, and a meet-cute in a cemetery. It was barely three pages long.

There’s a beauty in recognising the suburbs, buildings, households, families that live in New Zealand books.

Looking back, I think I would’ve been more engaged with writing from local authors. Over the last 12 years, having studied English Literature from NCEA Level 1 through to a university degree, I have read over 100 books, including Brontë, Melville, Conrad, Dickens, Hawthorne, Wilde, Fitzgerald, and Shakespeare. My reading has certainly evolved from my younger self and I would call myself a pompous ass.

These name drops are meaningless compared to New Zealand’s literature that was modern, legible and actually entertaining. New Zealand has a rich literary landscape that transports readers to local lands with meaningful history. Witi Ihimaera, Katherine Mansfield, Patricia Grace, Kari Hulme, Dominic Hoey. There is too much admiration for dead writings from the other side of the world. There’s a beauty in recognising the suburbs, buildings, households, families that live in New Zealand books.

Kyle Mewburn

Throughout school, I was an avid reader. Being bludgeoned and bored half to death by Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice nearly put an end to that. I wanted to read books that let me escape my rather dull reality for a while, or helped me better understand humanity and the world. Shakespeare seemed as much a pointless waste of reading time then, as it does now. Several of my ex-schoolmates still fondly recall reading Shakespeare, and our class trip to a small, backstreet cinema to watch Laurence Olivier as Shylock. I can only vaguely recall it because I fell asleep halfway through. Ironically, none of them are still readers.

My reading foundation was built on Stephen King, James Herbert, Michael Crichton, Frederic Brown and Agatha Christie. If there’d been such a thing as YA back then, I’d have certainly devoured them as well. Ideally, English reading curriculums should nourish growing minds by focusing on stories which directly relate to the contemporary lives of young readers. Stories which instil empathy and compassion. Stories which expose readers to new thoughts and different realities. Stories which look forward, not backwards.

I still firmly believe insisting anyone should read classics of any ilk is both condescending and utterly counter-productive. Reading should be a journey of discovery, so young readers should be given as much free rein as possible. Creating a society of readers should be the goal, not creating a society of ex-readers who were all forced to study Shakespeare.

English reading curriculums should nourish growing minds by focusing on stories which directly relate to the contemporary lives of young readers.

As a writer, my goal is always to write stories which speak directly to my readers’ hearts. Ultimately I suspect I strive for exactly what Shakespeare strove for—to write stories which take my readers on an emotional rollercoaster, sprinkled with laughter and insight. Stories which will linger long in my readers’ memories.

Poata Alvie McKree

The new curriculum should empower English teachers to better educate, enlighten, and encourage their students.

The new curriculum should empower English teachers to trust their instincts and select literature that will truly engage, inspire, and educate their students. It is crucial that teachers have the freedom to introduce a curriculum that aligns with their students’ interests and experiences. This includes the freedom to challenge their students intellectually and expand their horizons by exposing them to worldviews they might not otherwise encounter.

Reflecting on my journey through intermediate and high school English, I am filled with gratitude for the literature that shaped my understanding. George Orwell’s Animal Farm, a book I encountered at the tender age of 11, was my first taste of the power of satire and its ability to address significant societal issues. This literature opened my eyes to concepts of inequality, racism, and sexism, and while our understanding of these issues has evolved, the reality of certain sectors of society considering themselves ‘more equal than others’ persists.

Similarly, The Diary of Anne Frank opened my eyes to the suffering of others; I learned that oppression wasn’t the sole experience of black and brown people. Until then, I had only associated oppression with people who looked like me. More importantly, it introduced me to faith, hope, courage, determination, and love as valid responses to suffering and brutality. It taught me that there could come a time when it would be appropriate to disobey edicts issued by morally corrupt authority figures; that people with power do not always wield it responsibly—and that, in the end, we must trust our own judgement, testing everything against the truth within.

If you know a book, a play, a poem, or any form of literature that could benefit and enhance the education of a young person in your life—share it with them. You may be the only one who does.

Could my high school English teachers have done better? Yes. If they’d known better. Of my own accord, outside of prescribed texts, I read Maya Angelou’s five-book autobiography, Toni Morrison’s Beloved, and Alice Walker’s The Color Purple; all given to me by a Fijian-Chinese-Tongan friend, whose high school English teacher gave her a list of literature exploring the lives of people who looked like her. James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time and The Autobiography of Malcolm X were life-changing and came through a boyfriend who wanted to impress me (or perhaps it was the other way around). My mother made a spectacular 14th birthday gift of Patricia Grace’s Cousins, Witi Ihimaera’s The Matriarch, Keri Hulme’s The Bone People, and Janet Frame’s To the Is-Land; all of these entered my life at a pivotal moment of identity formation and shaped my thinking about the world. I’m not sure what the proposed curriculum changes will bring to our current generation of students, but may I suggest we don’t leave it all in the hands of their teachers? If you know a book, a play, a poem, or any form of literature that could benefit and enhance the education of a young person in your life—share it with them. You may be the only one who does.

Caren Rangi

As an introverted 13-year-old and one of the very few Cook Islanders at my high school, it seems ironic now that my English class was a place where I felt centred, connected and largely in control of things due to my love of words and reading. Though I very rarely got to read texts with characters or scenarios that reflected my own Cook Islands heritage and upbringing, I had discovered early on in life how the written word could magically transport you to places and situations of wonder (cue sparkly music…).

Of all my teachers throughout my secondary school years, my English teachers are the ones who had the greatest impact on me, because of the many worlds they opened up for me through the choices of books, plays and poetry. John McKenzie, or J Mac as we called him (behind his back of course), introduced me to a smorgasbord of literature and authors—from Witi Ihimaera, to S.E. Hinton’s The Outsiders, and to James K Baxter. Miss Affleck encouraged us to write our own stories and helped us produce plays and delicious musicals, which were a social highlight! In hindsight I would have loved to have explored the works of Pasifika literary giants Albert Wendt, and from my own homeland Alastair Te Ariki Campbell.

Though I very rarely got to read texts with characters or scenarios that reflected my own Cook Islands heritage and upbringing, I had discovered early on in life how the written word could magically transport you…

If I had seen more of myself reflected in our English curriculum then perhaps it would have reduced my struggles at times to balance my different home and school lives. Today I greedily lap up the sumptuous wide and deep Pasifika offerings from Karlo Mila, Selina Tusitala Marsh, Tusiata Avia, Audrey Brown-Pereira and Nafanua Kersel, just to name a few on an ever-growing list. And I rejoice that my 17-year-old daughter is already a prolific writer and has had two of her poems published, and loves English classes even more than I did.

Penny Ashton

I have spent the last 16 years as a full-time actor who writes and performs my own adaptations of literary classics. A surprising fact to my 18-year-old self who dropped university English faster than you can say ‘good god this shit is boring.’ Especially my Shakespeare paper where dismal lecturers drained any laughs out of comedies whose texts sat stagnant on a page. Shakespeare comes alive when it jumps off the page and slaps you in the face, when it is heavily edited and when it is performed or taught by someone who knows what the hell they are actually saying. I was put off and bored by slavish adherence to archaic words and stayed that way for 20 or so years.

But in going back and researching my new solo Shakespeare adaptation The Tempestuous, I was reacquainted with just how beautiful the poetry can be, the epic characters and storylines, and how funny and downright filthy Willy can be—tongue in your tail anyone? Also harvesting his best lines was like English language idiom bingo. Basically you’d be in a pickle on a wild goose chase not for the faint of heart to find anyone who has bedazzled our language more. His enduring legacy for dictionary references has never been surpassed.

I think the only people who should make decisions for their classes are their own teachers— not a questionable advisory group

But would 13-year-old me have given a toss about this? I don’t know. I do think there’s huge value in studying Shakespeare for his legacy, for his place in the history of live performance and as a lens for teaching history. But I think the only people who should make decisions for their classes are their own teachers— not a questionable advisory group with input from only three Auckland schools, formed seemingly in a politically motivated backlash against the former government. That sounds a bit like Much Ado About Nothing.