Frank Wilson is an initial education lecturer at Te Herenga Waka and works for the Aotearoa Social Studies Educators’ Network. Here she explores two new Aotearoa histories texts through the lens of a critical literacy framework in light of the recently implemented Aotearoa New Zealand’s Histories curriculum.

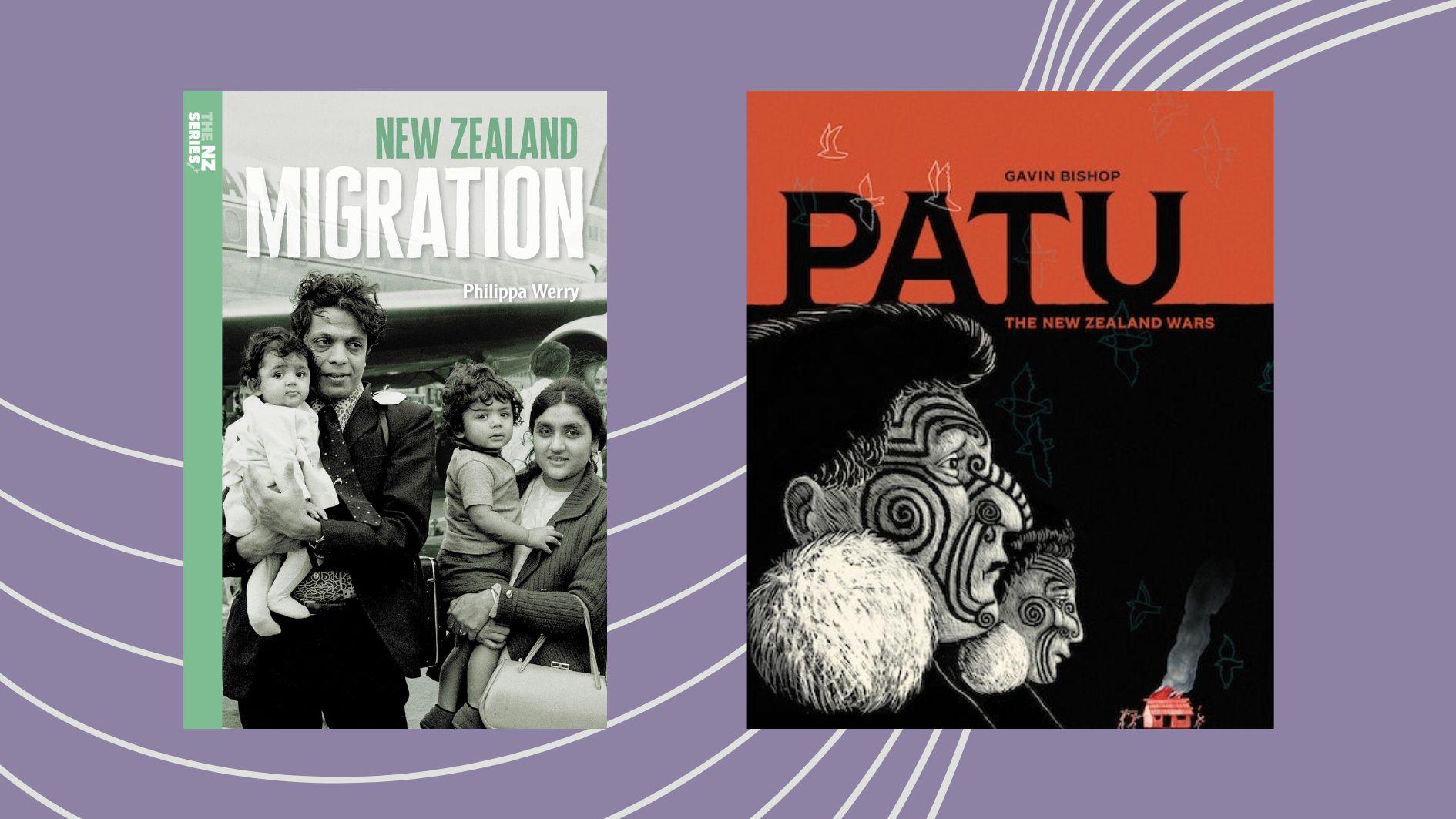

It’s a big call to write any history text, and particularly one aimed at younger readers. Gavin Bishop and Philippa Werry are both well known writers for children, so I was excited to explore how their books could be used in the classroom.

With the introduction of the Aotearoa New Zealand’s Histories curriculum and the soon-to-be-released Common Practice Model, teachers will need to apply the practices of critical literacy when approaching history texts with their students.

Critical literacy is more than critical thinking. It involves identifying how texts position readers by analysing inclusion, exclusion, and representation. At the heart of critical literacy is an understanding of the relationship between language and power (see page 8 of the Common Practice Model).

The author of any history text needs to make many decisions about what to include, what to amplify, and what to leave out.

Thinking with a critical literacy framework enables us to approach history texts with curiosity, and interrogate their approach. It helps us to think about a history text not as indisputable facts, but as something written by a real person who has made choices along the way, uncovering new information, or shining a new light on information that is commonly known. The author of any history text needs to make many decisions about what to include, what to amplify, and what to leave out. With that in mind, I decided to use a critical literacy framework with two new texts that explore aspects of our history: Patu by Gavin Bishop, and New Zealand Migration by Philippa Werry.

Both Bishop and Werry have distilled tonnes of information into bite-sized pieces. Patu has Bishop’s glorious illustrations, and has a matte cover that calls to be stroked. It definitely stands out from the crowd and will be one that children pull from the shelves often. In contrast, New Zealand Migration lends itself to serious study—it looks like a textbook, and will appeal to young people who are wanting to move away from picture books, but perhaps don’t have the reading level to cope with an adult book.

Critical literacy invites us to ask whose voices are heard and whose are missing

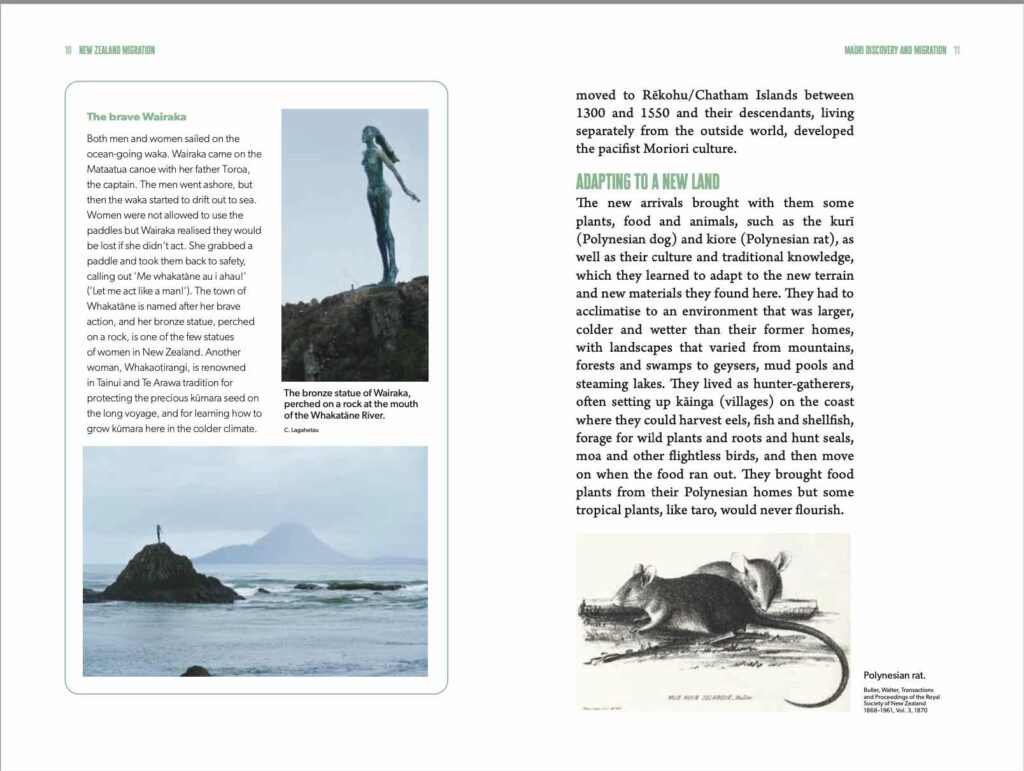

Covering such a vast sweep of history, Werry has done really well in including so many major groups of migrants to Aotearoa New Zealand. Different groups are introduced mostly in historical sequence from the first arrivals to our shores, and she includes diverse groups other than just ethnic groups; there is a section about the Deaf community, Jewish migration, and other disability groups. The long list of acknowledgements suggests she has done her research and has incorporated feedback from people who are descendants of the various groups.

However, I do get the sense that some important voices are missing. The blurb on the back, and the conclusion, both confidently state ‘Everyone in New Zealand is an immigrant or descendant of immigrants.’ While this is true for all Tauiwi, and most hapū and iwi have origin stories that show descent from Hawaiiki, not all do.

In one section, the word ‘pranksters’ is used to describe the people who persecuted early Chinese migrants by destroying their food and throwing bricks through their windows. This could be language coming from a primary source—I could see it being used in the Pākehā newspapers of the time, but it doesn’t seem like the way the victims of those crimes would have described them. Either way, this language is hurtful and providing context of its use would have been helpful.

[Bishop’s] book is clearly based on mātauranga and tikanga, and it’s lovely to see how he weaves these together with many publications to create his historical narrative.

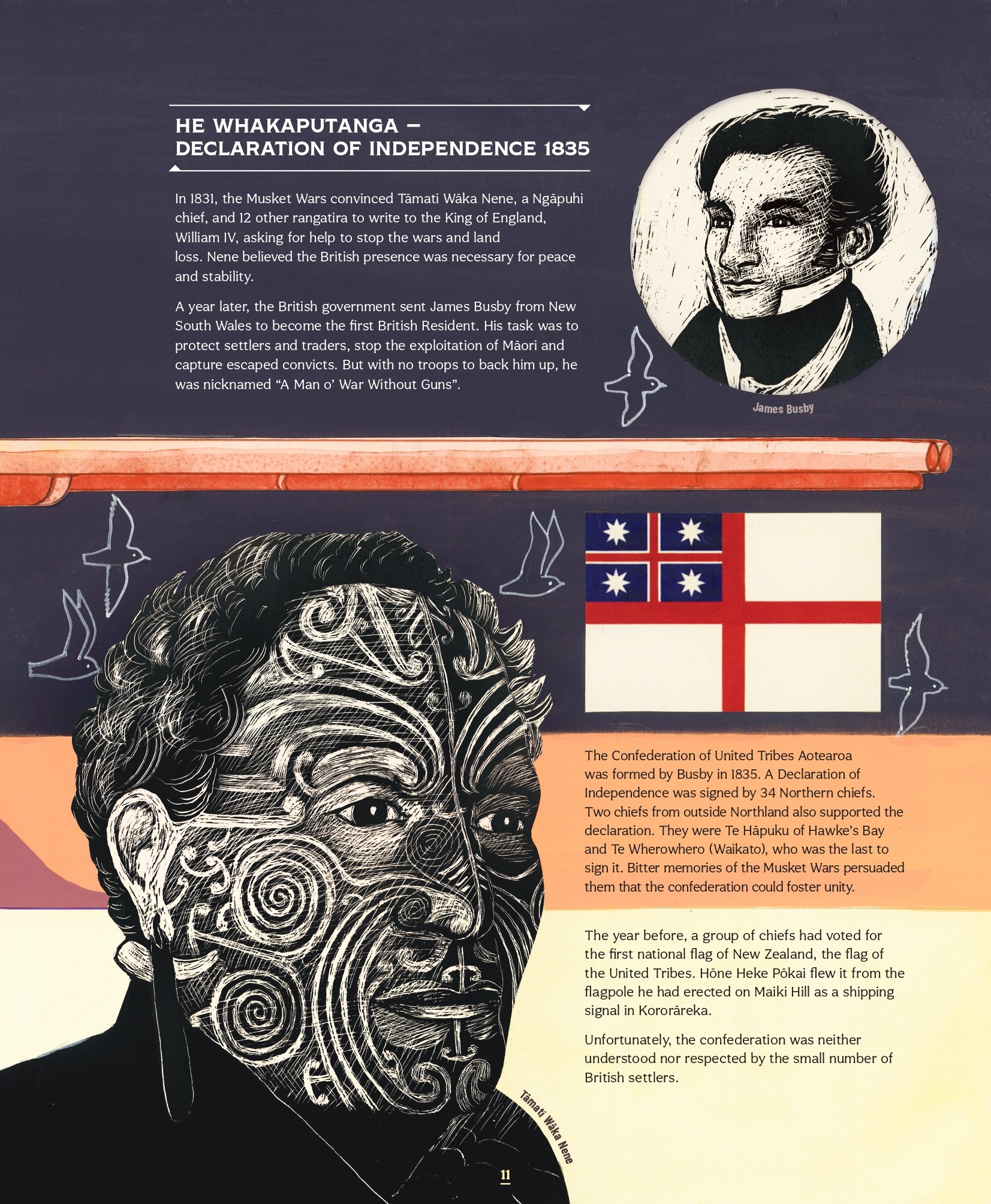

In Patu, Bishop had fewer voices to cover, but he has done it in an intriguing way. His book is clearly based on mātauranga and tikanga, and it’s lovely to see how he weaves these together with many publications to create his historical narrative. Māori voices and experiences come through loud and clear. I was glad to see Te Tiriti being referred to by its reo name, and that Bishop gave space to those who didn’t sign. I was troubled by the fact that on the Tiriti spread, only the British William Hobson is named—the Rangatira Māori who appears to be about to sign Te Tiriti is unnamed. Is it Wāka Nene? The moko is not the same as Wāka Nene’s so I would love to know who Bishop is depicting.

Bishop includes his own whānau, the MacKays, in the story (although that really confused my kids; they were expecting the MacKays to have a pivotal role in the New Zealand wars!). I think the inclusion of his whānau invites careful unpacking with students. It tells a subtle story of the impacts of colonisation on his whānau that many will resonate with.

Critical literacy invites us to explore how texts position us as readers

As you might imagine—with its textbook style—New Zealand Migration takes a mostly dispassionate approach to historic events, although some small anecdotes give us a glimpse into what life may have been like for the people. One of the Dalmatian stories inspired my children to open Google Maps to find out how long it would take to walk from Foxton to Palmerston North (10 hours!) and discuss how much longer it would take without the paved roads.

This mostly dispassionate approach made more emotive expressions stand out. For example, in the section about whalers and sealers, Werry states they ‘came to club the seals to death’. This struck me as an example of presentism, encouraging us to judge the actions of the whalers and seals by the laws and standards of today. While I’m sure the sealers weren’t all sweetness and light, the seals provided their livelihood and more humane ways of killing them would probably have been costly or not invented yet.

The narrative arc that Bishop takes the reader through deftly shifted my children from being excited to read a book about war, to a sombre sense of contemplation as they were led to understand how the actions of these men impacted people both in the past and today. Patu is definitely a book that leaves the reader feeling heavy.

Critical literacy invites us to explore how power is established and discussed

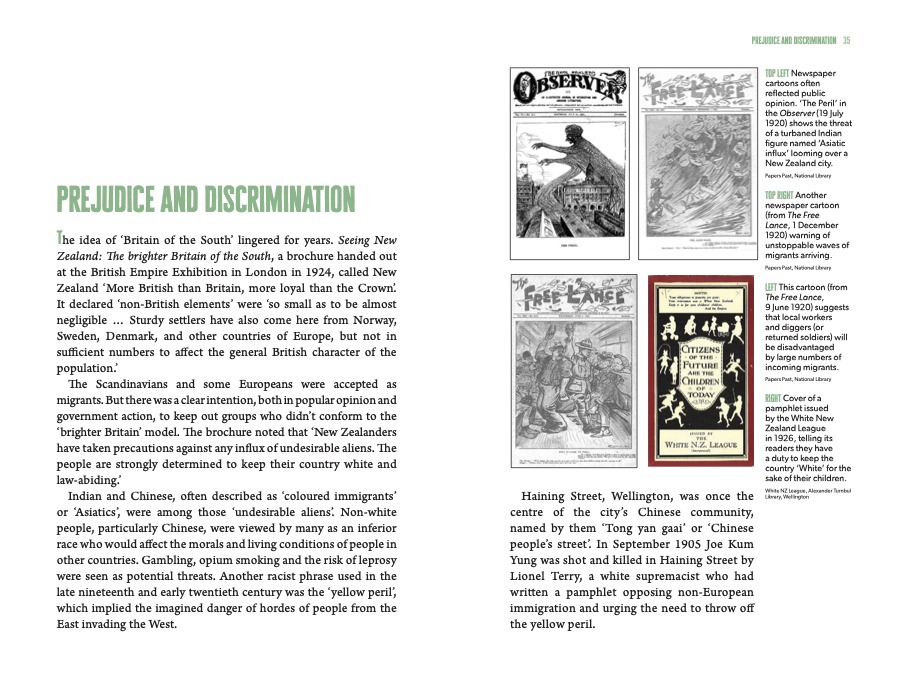

In the first section about British arrival to Aotearoa, I felt like Werry tended to be slightly more sympathetic to the British. However as I read on, I was impressed that she didn’t shy away from some of the unlovely parts of our history. She covered racist government policies, The White New Zealand League, and discussed the consequences of power and colonisation on Māori. It’s great to see a New Zealand history book that doesn’t talk down to young people or assume that some parts of our history are too upsetting for them.

I was impressed that [Werry] didn’t shy away from some of the unlovely parts of our history.

The title of the book lends itself to a critical discussion with students. With the new histories curriculum being called ‘Aotearoa New Zealand’s histories’ and Aotearoa or Aotearoa New Zealand being common usage, it seems an odd choice to only use New Zealand, particularly when starting with Kupe.

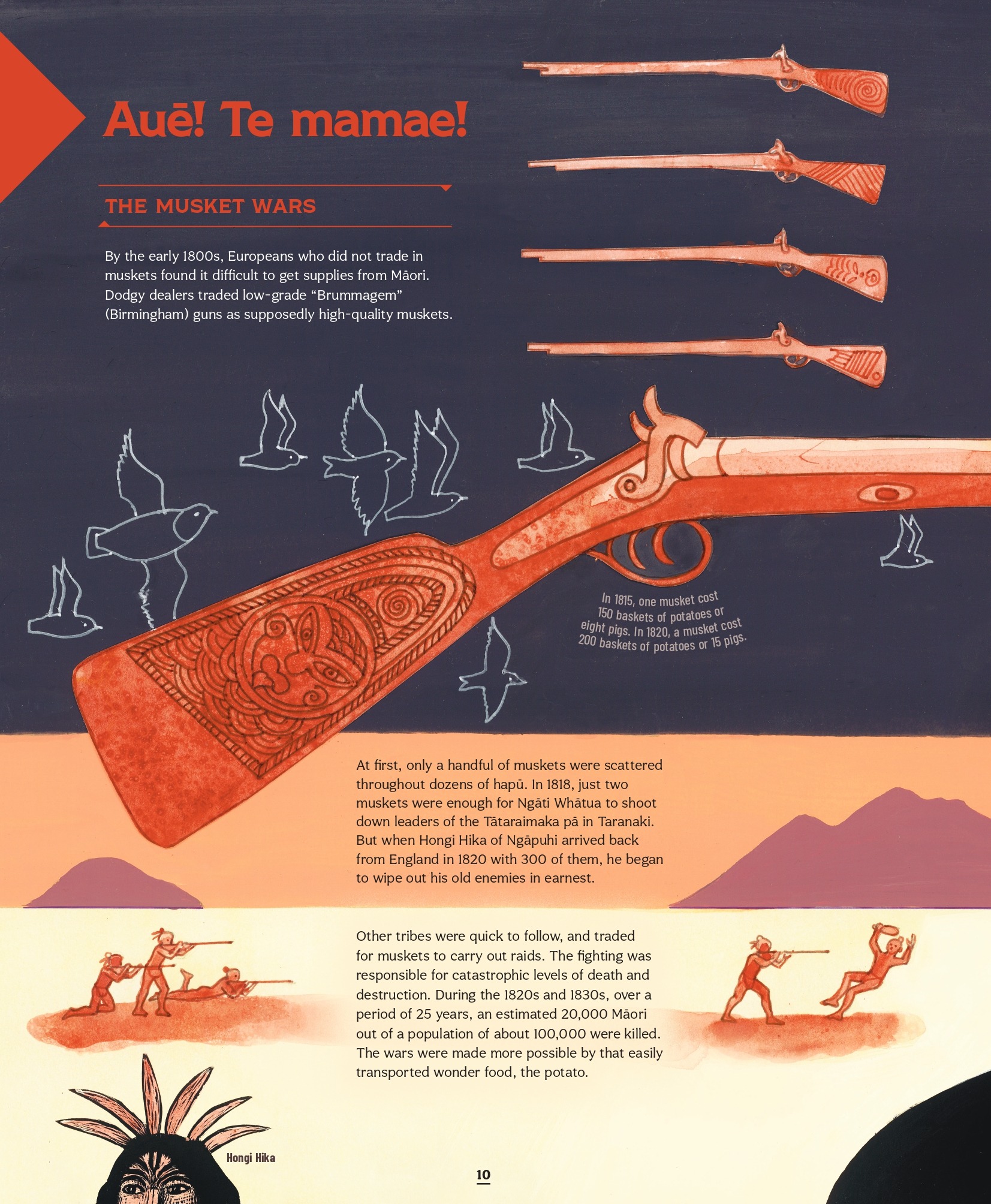

Power is, of course, the major impetus in war. In Patu, Bishop skilfully weaves in aspects that gave different groups power—from the potato which freed up more time for war, to the introduction of muskets, religion, He Whakaputanga, Te Tiriti and then finally to the legislation which had the same devastating effects on Māori society. He also doesn’t shy away from the unlovely histories, detailing how various British representatives acted in ways designed to take power from Māori in order to acquire land.

Critical literacy invites us to verify information

I would have loved it if New Zealand Migration had been written with footnotes, or some kind of referencing so that we could use it to model how to write informational texts. There were many times I would have appreciated being able to look something up—sometimes to verify it, but mostly to find out more information about the event. The small format of the book makes it hard to read some of the images and I hope that the publisher puts out a list of the images with links for their digital sources; having an image up on the big screen in the classroom would be very helpful.

Patu is quite different in that all the images are drawn by Bishop, but I still would have loved footnotes or specific referencing so that we could check sources or find out more. One part in particular encouraged further exploration—In the Tangata Whenua section about life when Polynesians first settled in Aotearoa, Bishop writes:

Over several centuries, horticulture became widespread. Men cleared and dug the land. Women planted and weeded.

This made me wonder whether gender roles were, in fact, that binary, so I asked Professor Angela Wanhalla (Ngāi Tahu)—who specialises in Māori, New Zealand and women’s history—and she stated that gender was often far more fluid than what was written in history books; gender was not a major factor in how society operated. Instead, whakapapa and status mattered far more because women who had illustrious whakapapa were leaders. A quick check of Bishop’s references reveal very few women, perhaps an expansion of his references might lead to a less colonial gendered view? I look forward to seeing what he might produce in future!

It’s wonderful to see so many new books coming out recently in light of the newly compulsory histories curriculum. I could see both these books used at all phases of learning from Year 4 up, with teachers choosing passages that suit the Big idea and Know contexts they are focussing on. Teaching children to approach these with curiosity, and with acknowledgement of their authorship, will hopefully help ensure they grow up to be critical readers of any texts they read—whether it is a social media post, a government press release, or a history book. The ability to think about what, how, and why something is written will benefit us all.

Frank Wilson

Frank Wilson is a lecturer in initial teacher education at Victoria university, specialising in social studies and literacy. She also works for the Aotearoa Social Studies Educators Network supporting teachers to develop their history and social studies programmes.