Kate McIntyre interviewed Mandy Hager about her new title Protest! Shaping Aotearoa, delving into how she chose her themes, what protests can achieve, and how she is supporting the younger generation.

It’s easy to take the rights we have for granted. The 40-hour-work week, the right to marry who you love regardless of gender, and the right to vote have not always been guaranteed. In fact, they were fought for in long, laborious, difficult campaigns waged by protestors.

“When you understand the struggle it took to attain those rights, you honour them and you protect them better, as opposed to believing they were always there,” says young adult author and longtime activist Mandy Hager.

“When you understand the struggle it took to attain those rights, you honour them and you protect them better, as opposed to believing they were always there.”

But do New Zealanders understand and honour those struggles? When you march, you’re likely to get honks of support, smiles, waves, and raised fists in solidarity from onlookers, but you’re also likely to get jeered at and told to get a job. For many, protest is considered a waste of time by people who have nothing better to do than complain. Maybe this is because so many of us live comfortably with the myths we are told, and it’s the job of protestors to bring those ugly truths out into the light and reveal them for what they are.

Mandy Hager’s new book Protest! Shaping Aotearoa follows on from Hindsight, offering young people another accessible non-fiction book about New Zealand protest history, only where Hindsight focused on four key issues, Protest! presents us with dozens. The range of issues and figures presented in Protest! paints a very diverse picture that you might not see as much of in other accounts of our protest history, and it makes me hopeful for young readers, that being able to see themselves in these past activists might help them to realise that they too can be agents for change and justice.

The issues in which we protest are often ones which affect our lives and the lives of our loved ones every day, and to get out and protest often takes astonishing bravery. Mandy recounts the movement for homosexual law reform, in which many LGBT+ activists outed themselves publicly, knowing that they might go to prison for doing so.

“It’s not just a matter of walking down the street with a placard. It’s risking your whole life… I think that’s a feature of a lot of these protests, just the bravery of people being prepared to stand up and step up.”

The first protests in this country came from Māori who were resisting incursions on their tino rangatiratanga by the Crown. One myth which many New Zealanders believe is that New Zealand has “the best race relations in the world”. That is to say that settlers’ encounters with Indigenous people here were much more fair and harmonious than other countries such as Australia and the United States, but for tangata whenua, this is a myth that is weaponised against them when they draw attention to the Crown’s abuses, and erases over 200 years of injustice.

One myth which many New Zealanders believe is that New Zealand has “the best race relations in the world”.

“Their land was invaded and they were having it stolen off them and all their rights taken away,” says Mandy.

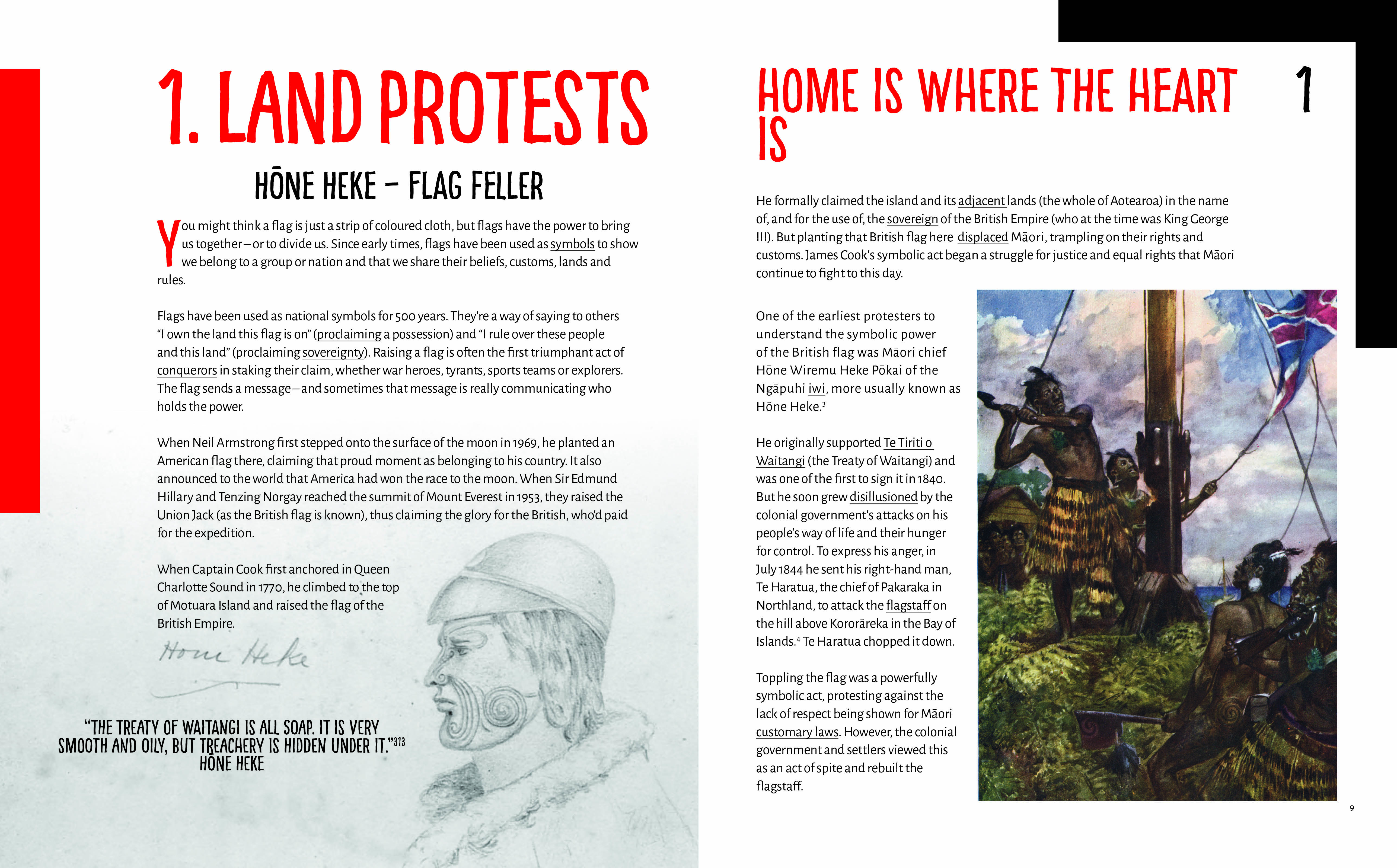

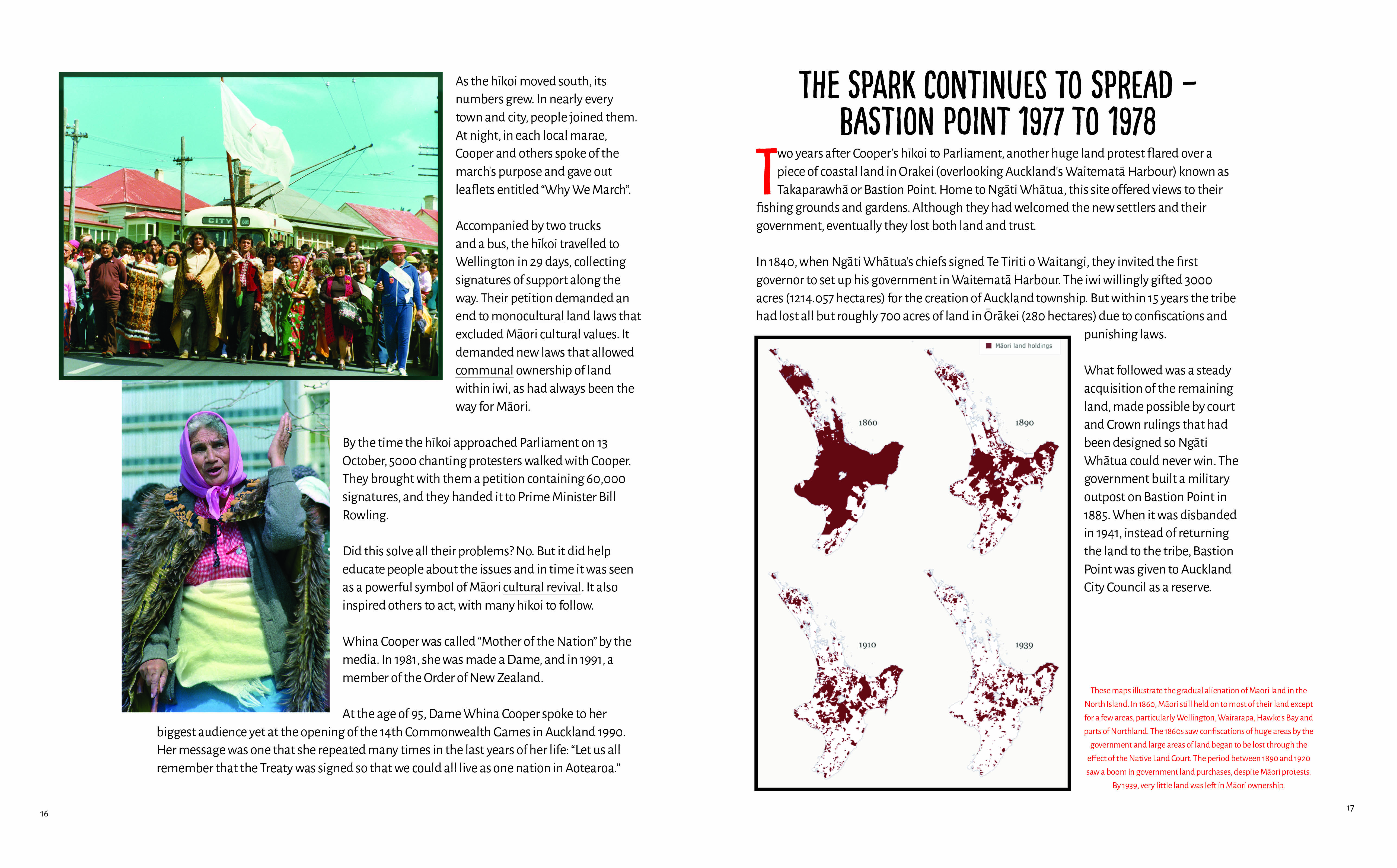

Protest! opens with a section on Māori protest history, starting with the protests of Hone Heke, a rangatira who was originally supportive of Te Tiriti o Waitangi and saw the potential benefits of a relationship with the Crown, only to become disillusioned later on. The section includes the peaceful protest at Parihaka, the land rights march led by Whina Cooper, and closes with the campaign to Protect Ihumātao—a cause which is very close to my own heart after I spent several months there in 2019. At the time which the book was printed, mana whenua of Ihumātao were still waiting for a resolution, but since then, the land has finally been returned, 158 years after it was stolen.

At the end of Protest! is a section on Pacific Island movements, including the Mau movement in Samoa and the Maasina Ruru movement in the Solomon Islands for national independence. This places the colonisation of Aotearoa in a broader context within the Pacific.

For Mandy, it was the patience and grace of Māori throughout decades of protest that stood out to her, that despite momentous injustice, abuse and violations of Te Tiriti o Waitangi, “the protests on the whole have been peaceful and, you know they’ve just bloody kept going!”

Mandy expresses a lot of gratitude to Māori and Pacific Islanders. “I think that the main thing that comes across is overall how patient they’ve been in trying to educate people to the issues at the same time as fighting for them… and allowing them into the space and saying ‘yes you can stand alongside us, but we really would like you to understand the issues from our point of view as well’, so not doing that whole white saviour thing either”.

It makes me think about what a privilege it was to be invited and welcomed into Māori political spaces in recent years. At Ihumātao, I only intended to stay for about a week, conscious that I might overstay my welcome, but within a matter of days, we were invited to move from our tent into the farmhouse and we were being asked for our thoughts at the morning briefings. While I can’t speak for everyone who visited the whenua during the campaign, I know that solidarity and Tiriti-partnership is possible, because I feel like we were living it over those months.

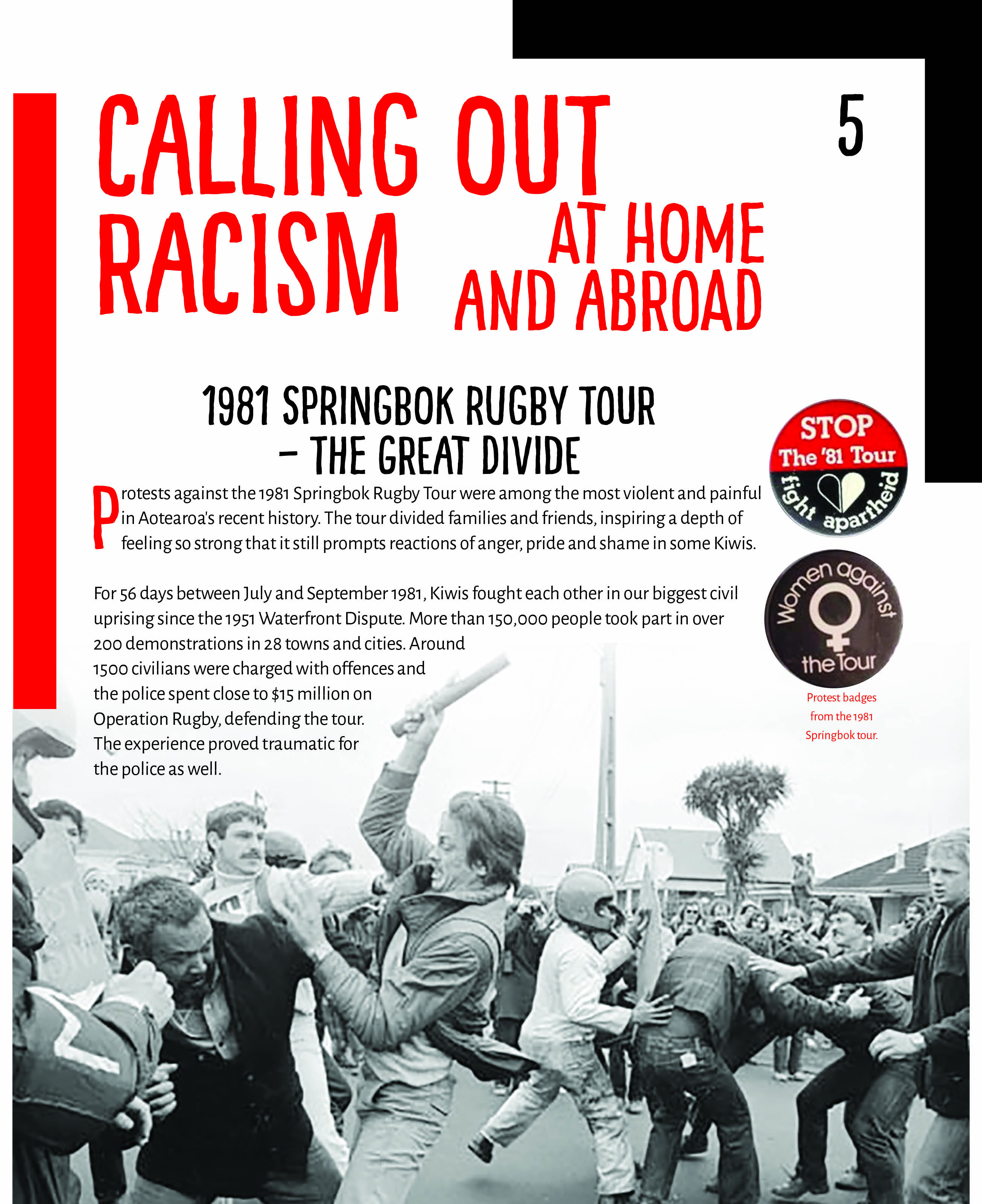

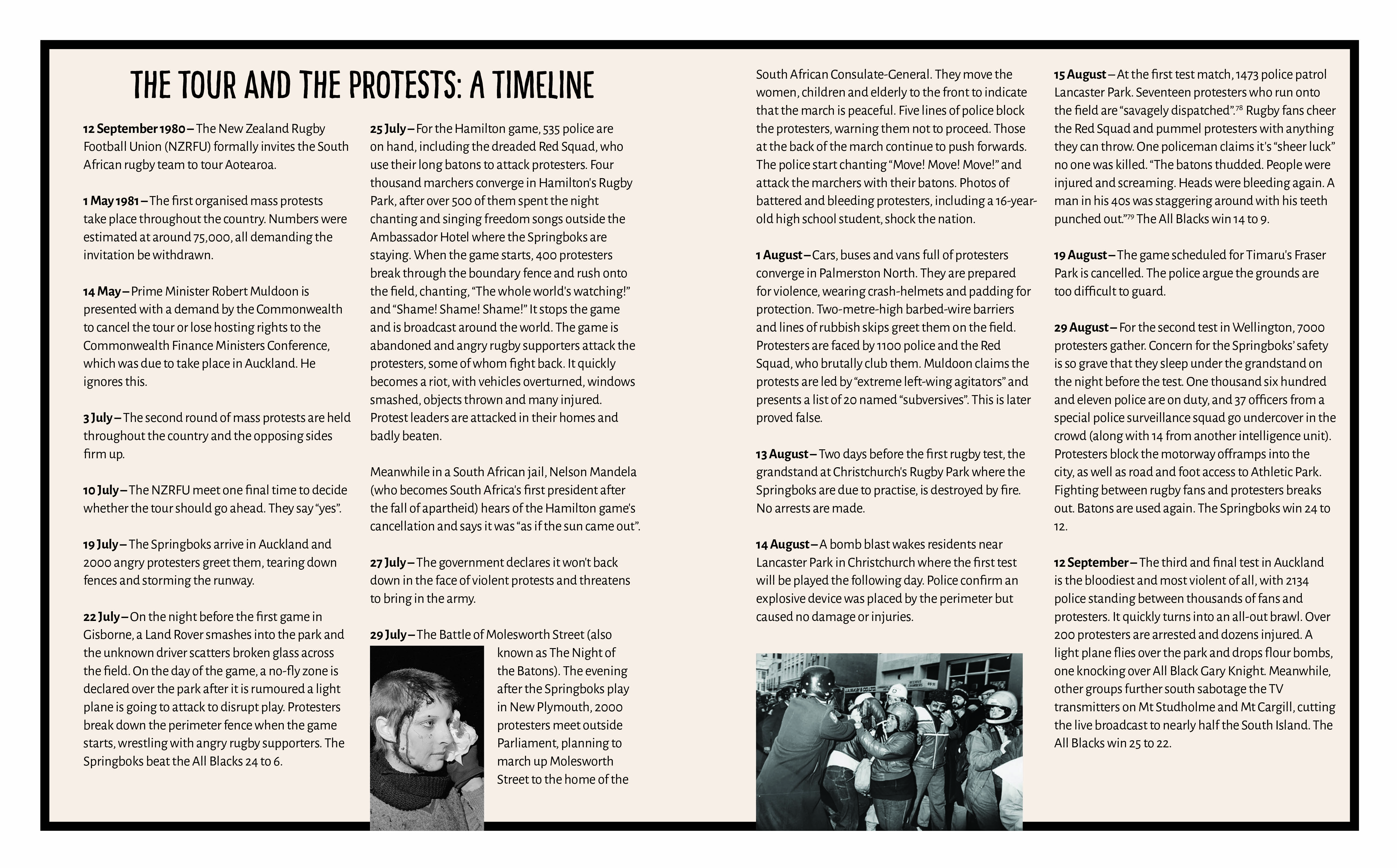

Throughout the book, the involvement of tangata whenua in a wide range of campaigns and movements is highlighted as well, from the protests against South African apartheid during the Springbok Tour, to movements for environmental justice, women’s rights, and anti-war movements, showing that tino rangatiratanga is not just an abstract idea about who gets to be in charge, but one that intersects with so many other issues.

Throughout the book, the involvement of tangata whenua in a wide range of campaigns and movements is highlighted…

Mandy also makes sure throughout the book to highlight the “amazing strength of will” that women have shown throughout these protests. “I think of Te Puea [Hērangi] sitting outside of the prison, just so that the men in there that were conscientious objectors could see her there, so they felt like they had somebody understanding… That was extraordinary.

“History has been written by men. It’s always the men’s stories, particularly in those labour strikes. Those women were the ones holding the families together and trying to scrape food on the table, yet they didn’t get a mention.”

“History has been written by men. It’s always the men’s stories, particularly in those labour strikes.”

Protest takes a lot of guts and bravery. Throughout history, many activists have faced mockery, abuse, state surveillance, police brutality, and social ostracism at the time which they were protesting, but time often shows that they are on the right side of history.

“Central and local governments were not necessarily the people who were actually protecting citizens’ interests and the country’s interests, and that it took ordinary people challenging what they were doing to actually make them step up in the end.”

For example, Mandy and I discussed the Foreshore and Seabed Act, in which Parliament overruled the Courts’ decision that the foreshore and seabed legally belonged to Māori, and the “Anadarko amendment” to the Crown Minerals Act, in which protest on the seas was made illegal. Alongside changing laws, there’s also a long history of surveillance on activist communities, either directly by the NZ Police, or through private security agencies such as Thompson & Clark.

When I was getting into activism, I was radicalised by seeing the documentary Operation 8, which details the mass surveillance and police raids on activists in 2007. Seeing that this happened under a Labour government shook away any trust I might have still had that even progressive governments have our best interests at heart. It was then that I decided protest is the best way for everyday people to make change happen.

Mandy believes that activists today who might not be appreciated now will be appreciated with time. On her mind are the school children who have taken to the streets to demand action from politicians on climate change. It’s disheartening to see them ridiculed by adults in power, but Mandy is sure they will be remembered as being on the right side of history.

“Climate change action covers every part of everybody’s lives… it’s going to impact on our safety, it’s going to impact on our security, our health, our democracy, our ability to be inclusive, all these issues,” says Mandy. “So it has to be the thing that we now tackle, making sure that all those human rights are protected, and social justice is protected within that. It cannot be ignored. It has to be part of every conversation now.”

“Climate change action covers every part of everybody’s lives… it’s going to impact on our safety, it’s going to impact on our security, our health, our democracy, our ability to be inclusive, all these issues…”

Of course, not all protests are honourable. Over Zoom, we chatted about some of the more dishonourable activism that’s been happening recently, including protests against lockdowns, mask wearing and vaccinations, the farmers’ protest, and self-described feminists who have been trying to undermine the rights of transgender people.

“People have the right to protest,” says Mandy, “but there are some that are there to benefit the rights of all, and then there are very small interest groups and discontented people and that’s kind of different… it is really hard to draw a line between which one is valid and which one isn’t.”

Although the government has responded very well to the Covid-19 pandemic, especially compared to many other governments, Mandy and I agreed there are valid things to criticise them for.

“Why weren’t nurses immediately given a pay rise? Why the hell are they having to bloody strike for it?”

Being an essential retail worker myself, who has been working through Level 4 on low wages without any pay increase, I have to agree, and I’m eager for us to stamp out this Delta outbreak so our nurses can resume their strike as soon as possible and we can all get back out on the streets again.

… I’m eager for us to stamp out this Delta outbreak so our nurses can resume their strike as soon as possible and we can all get back out on the streets again.

When I asked Mandy what her greatest challenges were writing the book, she said that she thought very hard about writing about Māori history as a non-Māori person.

“I was very careful writing in that introduction and talking about how this is my point of view,” she says, “It’s really important that [young people] realise that everything is curated through somebody’s mind or point-of-view, and so I would rather be upfront and say this is where I’m coming from.”

She also had trouble keeping to the word count, and not being able to include all the issues she would have liked to include.

Will Mandy continue to write non-fiction books about Aotearoa’s protest history? She has no immediate plans, but she greatly enjoyed working on Protest! and Hindsight. She would like to continue exploring these themes in her fiction, which she says can be even more powerful than non-fiction because you’re reaching people on a more emotional level rather than a critical one.

“It’s about building empathy, and opening people’s minds to a way of thinking.”

Activists can face setbacks. I often find myself worrying about moving backwards, and seeing our rights and freedoms rolled back. Mandy agrees that it’s always a risk, particularly looking at places like the United States, but she is hopeful that we’re moving in the right direction now.

“We acknowledge structural racism now. That’s the first time in my lifetime that I ever hear politicians acknowledging that, so those kinds of things I think are really positive.”

We acknowledge structural racism now. That’s the first time in my lifetime that I ever hear politicians acknowledging that, so those kinds of things I think are really positive.

In Protest!, she includes campaigns that were not successful, but which she believes we can still learn a lot from.

“Not all protests are going to be successful the first time, but if you continue to build on that and learn, you keep going… The environmental movements particularly, they really built over time, and hopefully will make a difference.”

Protest has a lot more power than people might think. Protest movements are shaping Aotearoa every day in ways which we might not always see. For activists like Mandy Hager and myself, we’ve seen the power that ordinary people can wield, we’ve seen the positive change that activists have brought us, and we’re energised by the growing numbers of younger activists.

Protest movements are shaping Aotearoa every day in ways which we might not always see.

“I see my greatest job is as an ally for younger people,” says Mandy. “To make sure that other voices can be heard in the future and to keep reminding people that change is possible.”

Kate McIntyre

Kate McIntyre is the daughter of booksellers John and Ruth McIntyre, who opened The Children's Bookshop shortly before she was born. She has involved herself in many environmental and social causes, including human rights for incarcerated people, LGBT+ marriage rights, stopping deep sea oil drilling, opposing the war industry and police violence, and supporting Māori land occupations. She lives in Wellington.