Award-winning author Melinda Szymanik shares her realisations about the skills and challenges involved in translating children’s books. Prompted by the publication of her books in foreign languages, Szymanik talks to Bill Nagelkerke about his experiences of translating and all that it entails.

When I was first published over twenty years ago, I had a very two-dimensional understanding of what it meant to have your work translated. As my career progressed, I believed that as my stories were often universal and did not rhyme, any translations that might happen would be a very simple proposition. I naively imagined a straight word-for-word exchange, especially with picture books which are generally less than 1000 words. The trick was in selling international rights—if I could just have that happen, the rest would be easy. Of course, having my books sell in foreign territories proved to be a hard nut to crack.

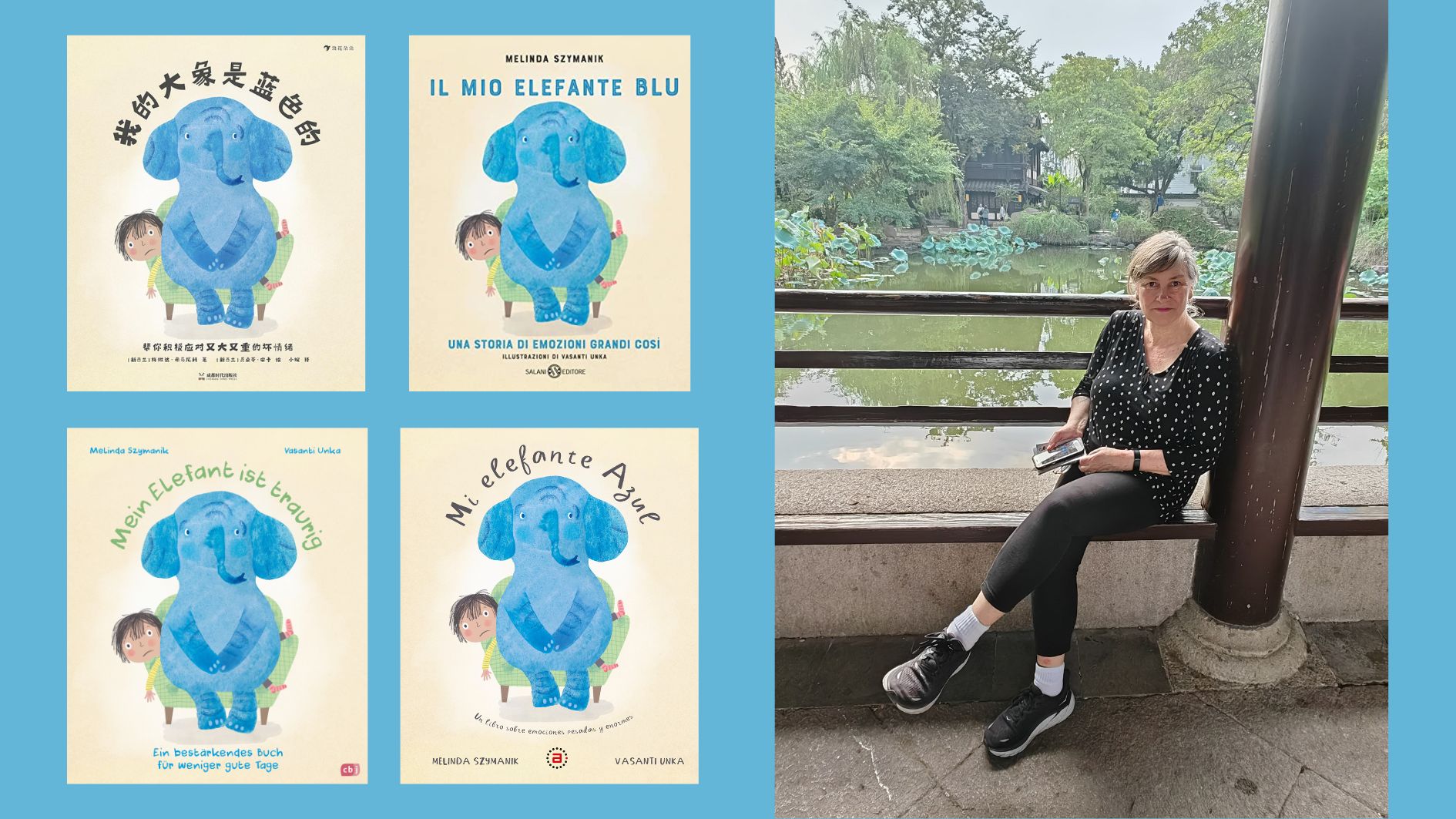

In the meantime, I had the good fortune to have my work translated here in Aotearoa New Zealand, although these initial experiences did not make me question my two-dimensional understanding. But recently I’ve come to think of translations somewhat differently. I spent time in Shanghai, China, on a two-month writing residency last year and—in attending events where our conversations were translated live—I was exposed first-hand to how much language is about so much more than just a word-for-word swap. Culture and history shape our thinking about language and how we respond to the same words, in such different ways. I also heard a Chinese writer say how upset she was at what had been lost in an English translation of one of her novels. How the nuance and subtlety of the original text, things she had deliberately crafted, had been carved away. Just a few months before my visit, a picture book of mine had come out in China in a translated edition. I began to wonder what these things might mean for my books that had been translated and whether some things will always be lost in translation.

But let’s begin at the beginning. I had been thrilled when my picture book The Song of Kauri (Scholastic, 2014), was chosen for translation into te reo Māori (Te Waiata o Kauri). Providing texts for all ages in te reo Māori is an essential part of preserving and protecting the language and growing its use, and translated books support this. Since 2014, three more of my picture books have been translated into te reo.

For the first three picture books translated there was very little interaction with the publisher or translator about the text. I’d assumed this was usual, still believing that translation was this simple, direct process. Then, for the most recent book, the translator wanted to replace a direct translation of a phrase I’d used with a Māori simile, and was that okay? Of course I agreed. The simile suited the tone of my story beautifully. I am as yet unable to speak te reo so I have been unable to read my translated books, but that was when the penny dropped: the simile met the needs of the te reo Māori reading audience much better than my original phrase. And a good translation would be comprehensively pulling the story into a different world view, where the words are underpinned by a culture and history different to my own. I realise this isn’t rocket science, but being monolingual has meant I’ve been unable to fully understand the impact of translation on my stories. I began thinking a lot more about translation and its implications.

They need to have a sound understanding of, and empathy for, the original text, as well as the ability to create a resonant translated version that respects both the source and the target language.

Bill Nagelkerke

How does a translator know what to do? While there are “degree courses in translation available” it was “learning on the job” for translator, author and poet, Bill Nagelkerke. Bill, a resident of Ōtautahi Christchurch with Dutch heritage, fell into translation work after his time on the Hans Christian Andersen Award jury. It meant many hours of reading children’s books in Dutch—“something which enabled me to reconnect in greater depth with my first language. Gecko Press was being established at around the same time and I wrote to Julia Marshall offering to translate any Dutch books that she needed translating. It went from there.” An early translation Bill worked on for a Dutch publisher was assessed by Flanders Literature who approved the translation and subsequently added him to a register of accredited Dutch translators. I asked Bill what he thought made a good translator. “They need to have a sound understanding of, and empathy for, the original text, as well as the ability to create a resonant translated version that respects both the source and the target language.”

Bill’s response also underlined having respect for the author. “My own approach is to try to be faithful to what the writer has written. If a horse ‘trots’, then it trots: it doesn’t ‘canter’ or ‘gallop’ or ‘run’, tempting though it might be to enhance the dramatic possibilities of the action. If the writer had wanted to use one of those words, they would have done so, as the original language provides for them.”

Of course translation isn’t the simple task of swapping one word for another. Words in one language might have no equivalent in another. Sometimes it is about everyday things such as local flora and fauna or country-specific idioms and colloquialisms. I asked Bill what he did when there is no translated language equivalent for an idea, concept or phrase appearing in the original text that he was trying to translate. “Rhyme as well as wordplay and idiomatic expressions often have no direct equivalent in the target language, so the translator needs to find examples that reflect the intent and spirit of the original. It can be difficult but, at the same time, this difficulty offers the translator an opportunity for an even richer engagement with the text. Word order, too, can vary between the source language and the target language. Dutch may use a compound word that has to be represented in English by several words.”

…the translator needs to find examples that reflect the intent and spirit of the original.

Bill Nagelkerke

I also asked what the general rule was for any changes or additions that might need to be made. In Bill’s view, “… there has to be a sound rationale for taking liberties with the original text. In the novel Iep! by Joke van Leeuwen I changed the title to Eep! as the original was likely to be pronounced incorrectly in English. I replaced, rather than translated, one or two of the random bird names listed in one of the chapters with the names of more familiar Aotearoa New Zealand birds. It made no difference to the story but the substitutions enabled me to match a humorous play on words in the original, as well as making the story resonate more for local readers”.

Onomatopoeic sounds can also present an interesting test for a translator, as Bill discovered with one of his first translations, Leo Timmer’s book Who’s driving?. It was “a story that appeared at first to be a very simple introduction to vehicular noises. This one required a visit to the central fire station to listen to the different sounds made by fire engines, once I realised that the sound of a European siren was obviously very different from a New Zealand one!” You only need to Google what a cat’s meow or a dog’s bark are named in other countries to realise we hear different sounds dominating.

I’d seen some of these challenges myself when my picture book My Elephant is Blue (Puffin, 2021) was picked up in some other markets. The expression ‘roly-poly’ was completely swapped out, becoming ‘hide and seek’ in Italian, and ‘badminton’ in German. These are minor amendments and understandable. Roly-poly, or acquiring grass stains on your clothing while hurtling horizontally down a hill, is apparently not a universal pastime. Who knew?

In Germany they also wanted to change the title. In My Elephant is Blue, the ‘blue’ descriptor reflects the elephant’s mood. In Germany, I believe ‘blue’ refers to being drunk, amongst other things. So understandably the title became My Elephant is Sad. The subtlety was lost, but it was a very minor thing—the elephant is still called Blue in the story, and reviews of the German edition showed the central themes hadn’t been affected. The change was mentioned before this edition of the book was published and I was given the chance to express my thoughts. Thus far I have never been heavily involved in discussion around any of the translations. I guess with picture books, while every word is carefully chosen to support the ideas and plot, the text is significantly shorter and somewhat less complex than the text that might appear in a novel. Nevertheless, it was nice to find (and made me a little envious) that Bill is sometimes able to discuss changes with the originators of the texts he has worked on (both long and short fiction), checking that any changes are acceptable, and that meaning and authorial intentions are maintained. “This was certainly the case with the minor textual changes to I’ll keep you close (Levine Querido, 2021). The editor (in New York), the author (in Amsterdam) and I (in Ōtautahi Christchurch) were in regular touch about how the work was proceeding. The author, Jeska Verstegen, endorsed the final translation of her very moving autobiographical novel. If an author can’t for some reason comment on the target language I guess it then comes down to trusting the people involved and the rigorous process of editing that is always an integral part of publishing any book.”

Rhyming can often be seen as a bridge too far for translation. However, Bill had had some experience with translating a rhyming text. Leo Timmer’s more recent books have been written in rhyme and when Gecko Press decided to publish English language editions, Bill was asked to provide a basic prose version which was then rewritten in verse by local poet James Brown. Bill noted, “the narrative arc in these books remains unchanged but the finished texts are very different from the original. They have become adaptations rather than translations.” I imagine having a proven record of sales in translation as Timmer’s books have, would make this process worthwhile.

But what if local features and language were an essential part of the story? Do we cede our stories to the culture of the acquiring publisher?

I’ve also wondered about books sold into other English-speaking territories. Small grammatical edits and country-specific word swaps (Mum for Mom) were made for My Elephant is Blue in the US. But this text was a universal kind of story. What mattered was the central theme. The setting was never country-specific and the language not reliant on local turns of phrase. But what if local features and language were an essential part of the story? Do we cede our stories to the culture of the acquiring publisher?

In a recent article by Aotearoa New Zealand writer Rebecca K Reilly, she talks about her award-winning novel Greta and Valdin (Best First Novel, 2022 Ockham Book Awards), lamenting what might need to be discarded for a US edition. “At some level we do seem to believe we need to be translated in order to be a part of the wider Anglosphere, and that’s something we should offer up ourselves in any type of international forum. I don’t know how helpful it is to our national identity to constantly view ourselves as anomalies who aren’t able to be understood, or to consider ourselves always from the perspective of outsiders first.”

It may well be that authors with international aspirations might self-translate stories as they write them, making them universal. Having grown up here on the literature of other English-speaking countries, decoding unfamiliar words and concepts like ‘pavements’, ‘sticks of butter’ and ‘moms’ broadened my world view. I coped with the foreign world presented to me between the covers of my favourite books—Famous Five, Charlotte’s Web, Little Town on the Prairie, Trixie Belden, The Wolves of Willoughby Chase. None of those books were altered to be more palatable to an Aotearoa readership and in my opinion the end result for me was a positive one. It seems ironic in a time when we are more connected than ever by the internet and social media that there is still overseas resistance to New Zealand stories. If it was possible, I would urge publishers to retain language and cultural references of the originating author if this is a feature of the original text. After all, this must have been a part of what won the overseas publisher over in the first place. There should be times when our native birds and local idioms can be preserved in translation. And some balance struck between immersing the story in the world view of the translated language, and retaining the quintessential elements of the originating language that teach us something about the culture from which the story came. After all, the more stories that cross the language divide, the more we might understand each other’s cultures and expand our understanding of what language is capable of. I still can’t help thinking of the Chinese author’s sadness at what had been lost in the translation of her text.

After all, the more stories that cross the language divide, the more we might understand each other’s cultures and expand our understanding of what language is capable of.

In the end we often can’t know whether anything is missing or altered when the original language of a text is one we don’t understand. It’s a leap of faith. I was encouraged by Bill’s views about the care he takes as a translator. I’d like to give the final word to him: “One of the great pleasures of translating a book is the realisation that you are enabling readers to become acquainted with a book they would not otherwise have had the opportunity to read.”

Want to read more about translating children’s books? Read The Magic of Translation by Nadine Anne Hura, first published on The Sapling in 2017.

Melinda Szymanik

Melinda Szymanik is an award-winning author of picture books, short stories and novels for children and young adults. She also writes poetry for adults and children, and regularly teaches creative writing. Recent titles include Lucy and the Dark (Puffin [Penguin RH], 2023) and Sun Shower (Scholastic, 2023).