Comics and graphic novels are a wonderful medium for kids and adults alike. Science communicator Katherine Hurst talks us through how science is portrayed in comic form and gives some great examples.

It’s 2023, so hopefully there’s nobody out there who still thinks comics are only full of superheroes wearing capes and shouting “kapow!” Comics today come in all shapes, sizes and styles, from webcomics to book-length graphic novels, and they cover a huge range of subjects. So while there are still plenty of Batman stories, there’s also a comic that gives you detailed information about the eating habits of fruit bats.

Science themes seem to feature in an increasing number of comics and graphic novels, both fiction and non-fiction. Climate change, allergies, the human body, space travel, COVID-19, myrtle rust… you name it, you can probably find a graphic novel about it.

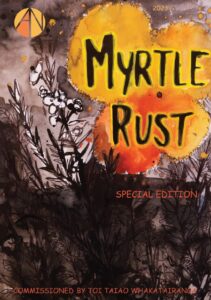

A comic about myrtle rust?

That’s right! Aroha Novak’s Myrtle Rust was commissioned by Toi Taiao Whakatairanga, an organisation which works with artists to explore public awareness around myrtle rust and kauri dieback. Rather than a straightforward explanation of the plant disease, this is a horror graphic novel with parasitic spores and experimental plant pathogen technology gone horribly wrong. It is very firmly set in Aotearoa, with frequent use of reo Māori and an ending reliant on a karakia. Its distinct style and restricted colour palette give it a wonderful sense of foreboding and decay, sure to appeal to many of its intended teenage audience.

There are no rules about how much “science” is in a science comic—some don’t feature science explicitly at all, and instead aim to make their readers more receptive to ideas.

Why create a horror comic about a plant disease? The point of most science comics isn’t to hand over a bunch of facts. They need to be entertaining enough so that people read them; once that’s achieved, some comics may be full of scientific explanations, but for others the main purpose may simply be to make the reader aware of an event or an issue. Many science comics show the process of how science is done, rather than focusing on the results. There are no rules about how much “science” is in a science comic—some don’t feature science explicitly at all, and instead aim to make their readers more receptive to ideas.

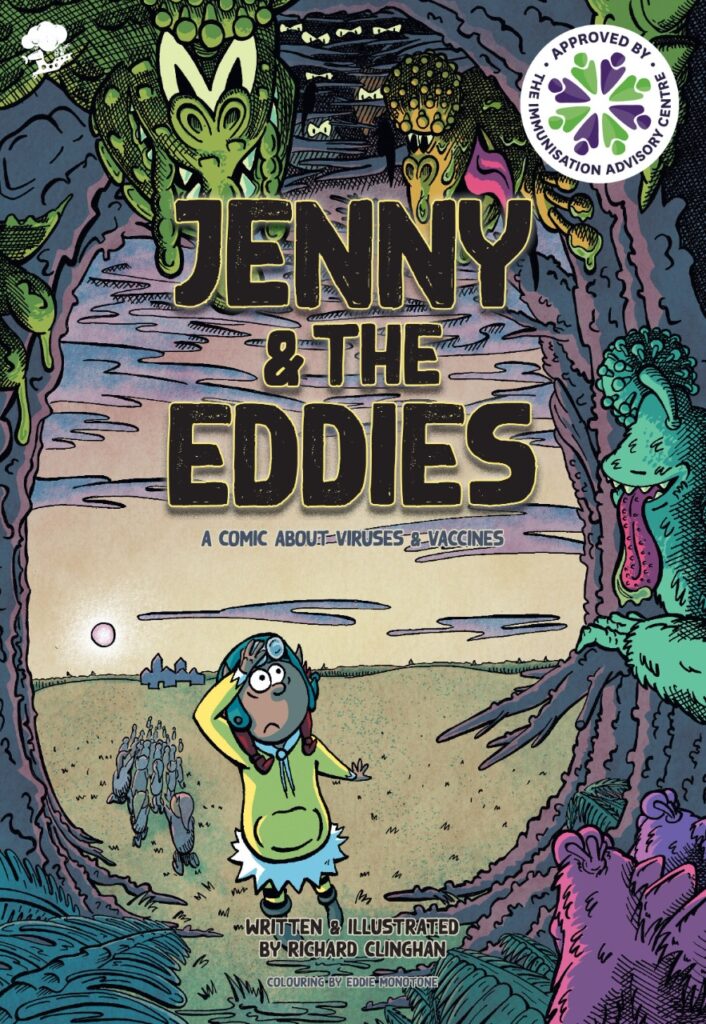

An effective example of this is Jenny and the Eddies, by Richard Clinghan, a doctor living in Aotearoa. In response to a measles outbreak, he decided to look at vaccines from a fresh perspective and asked the question: what might a vaccine look like based on the qualities it embodies? He came up with Eddie, a dog-like creature who is vigilant, brave, and loyal. Jenny is the elf who points out that the Eddies have been so good at keeping the forest monsters (the viruses) away, the villagers have been listening to the whisper monsters (anti-vaxxers) and have forgotten the suffering the monsters caused. It’s an enjoyable story with engaging characters; the message about vaccines is there, but readers are left feeling entertained, not instructed.

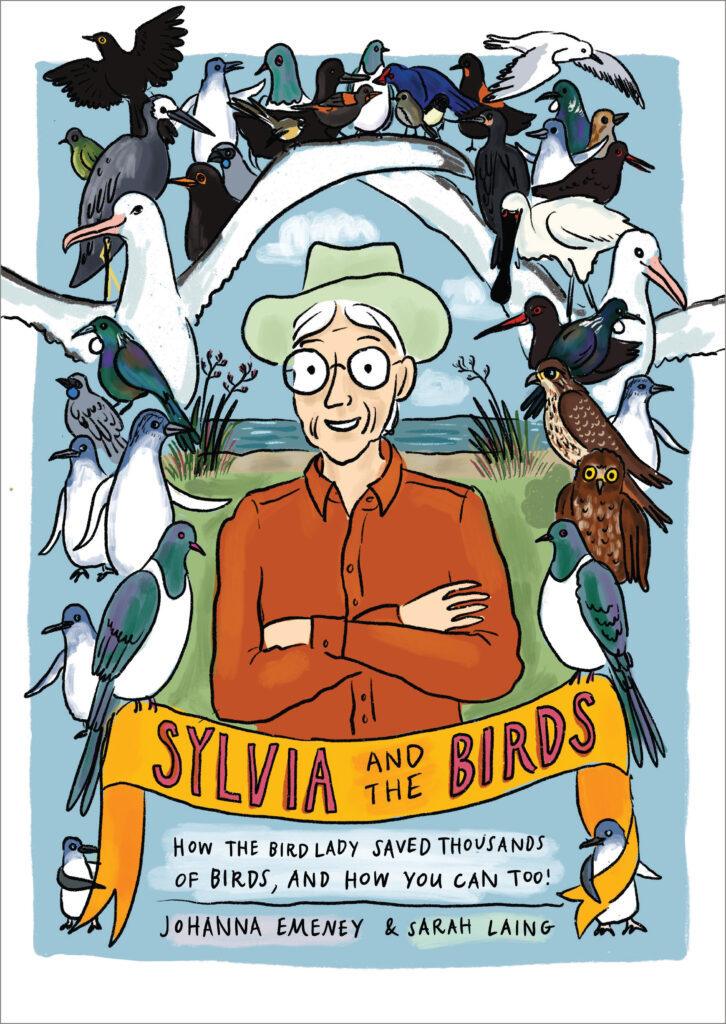

Sometimes deliberate instruction can be entertaining too. Sylvia and the Birds: How the bird lady saved thousands of birds, and how you can too!, by Johanna Emeney and Sarah Laing, warns explicitly in the title that you are going to be taught something! Combining a little of everything—graphic biography of bird lady Sylvia Durrant, activities, pages of text, photos, and how-tos, this beautiful book manages to transfer a lot of information in a very readable format. As well as telling the story of her life, cartoon Sylvia and her friends give the readers practical tips for helping birds—taking advantage of the comic format to be both entertaining and accessible. It’s impossible not to learn something!

Sylvia and the Birds

By Johanna Emeney & Sarah Laing

Published by Massey University Press

RRP: $39.99

While these three examples are all fairly recent and from Aotearoa, science comics have been around for a long time (Larry Gonick was writing his Cartoon History of the Universe back in the 1970s) and appear in many different countries (manga series from Japan include Cells at Work by Akane Shimizu and Dinosaur Sanctuary by Itaru Kinoshita). So why do so many people write comics about science?

Comics have several features which lend themselves well to communicating science.

First: some comics theory. In Scott McCloud’s book Understanding Comics, which examines comics as both an art form and a way of communicating, he suggests that readers do very different work when reading a comic compared to a book. A comic is more than just a sequence of images—what happens between the panels is often as important as what is shown in the panels, and it is the reader who has to imagine what that is. McCloud says, “By creating a sequence with two or more images, we are endowing them with a single overriding identity, and forcing the viewer to consider them as a whole.”

While comics can be read linearly, one panel at a time, they are also often read in a non-linear way. Comics researcher Matteo Farinella suggests that as the reader gains new information, they reassess previous panels. He compares this to science, which often requires readers to make connections between different areas of knowledge that aren’t arranged in a neat linear or hierarchical order. Comics also encourage rereading—the first read through might focus more on the words, and the second might look for more details in the images.

While comics can be read linearly, one panel at a time, they are also often read in a non-linear way.

Both science and comics rely on metaphors. McCloud suggests that everything in a comic is basically a metaphor or a symbol. Everything that appears in a comic has been simplified in some way by the artist, and there’s a rich visual vocabulary to show the invisible: when we see a speech bubble, we know that it means someone is talking, and when we see motion lines we know something is moving.

Science often uses metaphorical language, as scientists look for well-known experiences to explain their theories or illustrate abstract concepts—for instance electricity was modelled as a fluid, so we talk about the flow of an electric current. It’s important not to get carried away with a metaphor. They have the potential to give an incorrect understanding, or even to spread misinformation. Visual metaphors or new ways of seeing things (such as a microscope) can transform scientific knowledge too, as Farinelli describes in his comic Of Microscopes and metaphors: visual analogy as a scientific tool.

So science comics are particularly good for communicating complex concepts or things which can’t be seen, sometimes with metaphors—and sometimes with magic.

So science comics are particularly good for communicating complex concepts or things which can’t be seen, sometimes with metaphors—and sometimes with magic. There are many examples of comics that use some sort of impossibility to illustrate their science; whether it’s using time travel to visit extinct animals (Dinosaur Empire! (Earth Before Us #1): Journey through the Mesozoic Era by Abby Howard) or talking animals teaching us about genetics (Science Comics Cats: Nature and Nurture, by Andy Hirsch). This use of magic, when done well, seems to sit harmoniously in a comic with the science it is helping to communicate, in a way that it might not if we were reading just text.

Putting science subject matter into comic form doesn’t necessarily make it more interesting. There are plenty of boring and/or confusing science comics out there! Often there can be too many words—a science comic shouldn’t be a series of illustrated captions. There are many different art styles which appeal to different people, so the chosen style needs to match the intended audience. Stories and characters need to be engaging, and—very importantly—the science needs to be correct!

Who’s reading these science comics?

All of these features make comics a great medium for communicating science, but that’s only useful if the intended audience wants to read them. Luckily, many people of all ages find comics appealing and engaging, and particularly for reluctant readers or people with learning disabilities, they can be much more approachable than a fully text-based book. They’re also much quicker to read!

Not that there’s always a hard and fast line delineating comics from other types of book. Giselle Clarkson’s The Observologist: A Handbook for Mounting Very Small Scientific Expeditions includes comic elements among the pages of entertainingly illustrated text. And 24 Hours in Antarctica, by Andy Prentice—part of an Usborne series—could be equally at home shelved with the picture books.

One big reason people like reading comics is that they lend themselves to humour. Human Body Theater by Maris Wicks is a great example. A skeleton teaches us about the human body, throwing in everything from super-cute pictures of visceral muscles to a dancing chorus line of infectious organisms, and a piece of toast that’s really excited to explain the digestive system while it’s being eaten.

The best science comics have creators who are obviously passionate about both the characters and the content.

Graphic novels can successfully deal with sad or tragic topics too. Nick Abadzis’s Laika, about the first dog to be launched into space, tells the story of Laika from several perspectives including a dog-trainer, a scientist, and Laika herself. (This one is a real tear-jerker.) And Guardian of Fukushima by Ewen Blain and Fabien Grolleau, is based on the true story of Naoko Matsumura. After the 2011 earthquake and subsequent nuclear disaster in Japan, Matsumura went back to live inside the radiation zone so he could look after some of the thousands of abandoned pets and livestock. The story weaves in Japanese mythology, including Numazu, a giant catfish who lives underneath Japan and whose violent thrashing is said to be the cause of earthquakes. Climate change was the focus of Faction Presents “High Water”: New Zealand Comic Anthology, edited by Damon Keen, featuring speculative comics from eleven of Aotearoa’s most well-known comic artists. While more aimed at adults, these three titles show the breadth and depth that’s possible.

When it comes to serious health issues, graphic novels can be a great way of gaining not just medical information, but an understanding of how someone experiences the issue. Great examples of this are the semi-autobiographical El Deafo, by Cece Bell, about an anthropomorphised bunny that becomes deaf after an illness, and Smile, an autobiographical story involving a lot of dental treatment, by Raina Telgemeier.

From the personal to the global, science comics can work at any scale!

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, Siouxsie Wiles and Toby Morris collaborated for The Spinoff, producing images and animations on everything from flattening the curve to symptom checks, and from how a mRNA virus works to misinformation red flags. The comics were shared in their hundreds of millions, and adapted and translated by governments and organisations worldwide. Their clear and confident messages, in comic form, were far more successful than text explanations could have been.

In 2021, The Spinoff and the Science Media Centre, with support from NZ On Air, hosted the Drawing Science workshop to bring together researchers and illustrators from around New Zealand, in the hope of building relationships that may lead to similar collaborations. As a result of the workshop, there is now a free guide for researchers keen to learn how to collaborate with illustrators, as well as a directory of illustrators interested in working on science communication projects.

The Last Panel

The best science comics have creators who are obviously passionate about both the characters and the content. They are entertaining and informative, without being didactic. Comics have unique features which allow them to present complex scientific information in a way that is accessible to a wide audience, so we can look forward to a future with many new and amazing science comics!

Katherine Hurst

Katherine Hurst has had a variety of jobs including making superconductors and working in visual effects on The Lord of the Rings movie trilogy. More recently she completed a Master of Science in Society at Victoria University, and now works as a science communicator in Wellington.