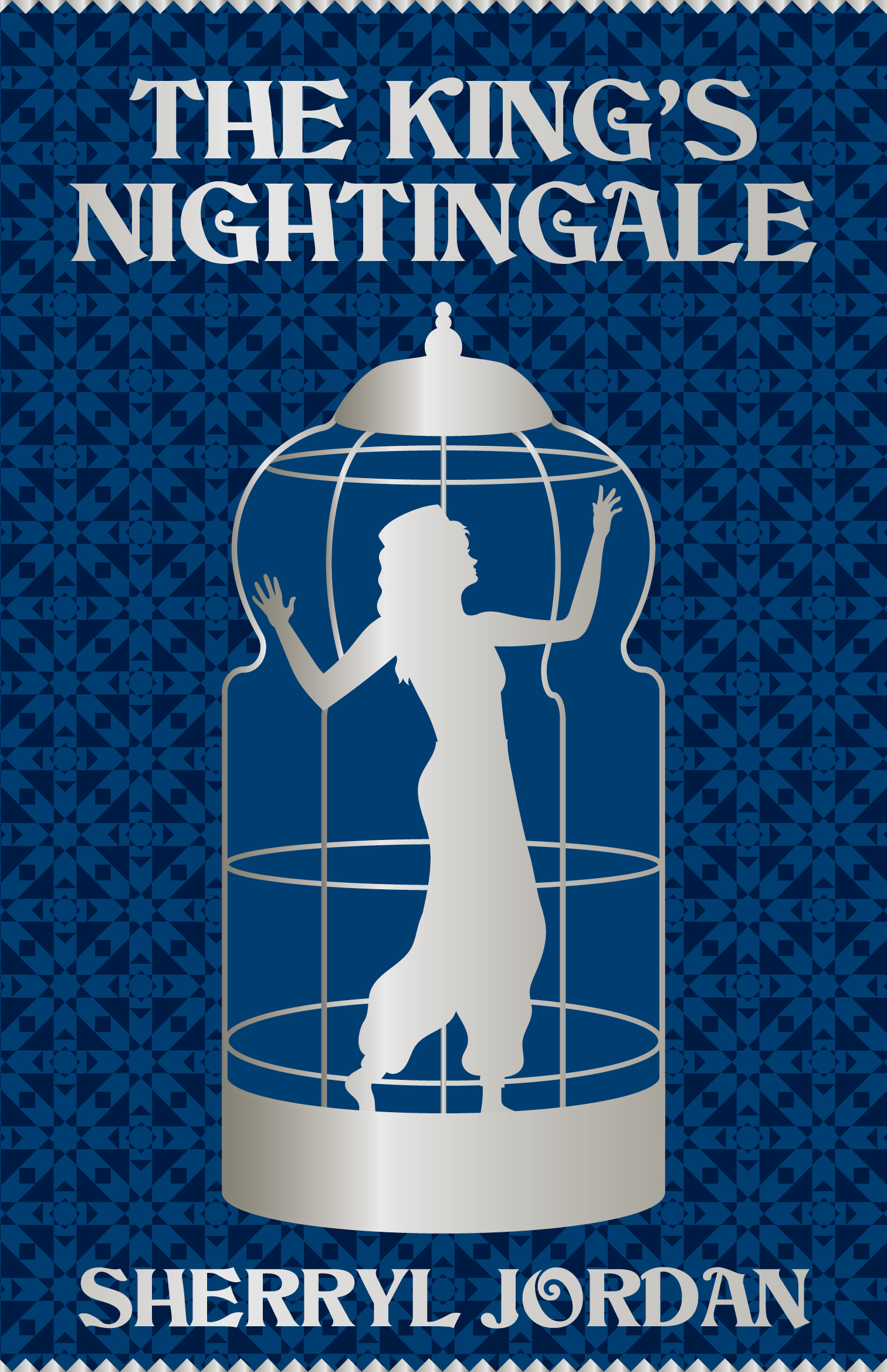

By Sherryl Jordan

We are incredibly excited to be sharing the first snippet from Sherryl Jordan’s forthcoming novel, The King’s Nightingale. Due out at the start of February, it’s another classic Sherryl Jordan dive into a new land – following Elowen’s journey to escape from her captors and free her brother.

Chapter 1:

In utter darkness the captive crouched, arms around her knees, head bent. She hummed brokenly to herself – a tuneless, melancholic sound – partly to block out the misery all around, partly in defiance of her fear. She could feel her brother leaning against her as he slept, and was startled when he spoke.

“Sing a song from home, Elowen,” he said, his voice hoarse from thirst.

“Why?”

“It would help.”

Slipping an arm about his shoulders, she realised how thin he had become. Since their capture she had seen his face only briefly, once a day when the grating above had been opened, and in that fleeting daylight she had seen how he looked older than his twelve years, his eyes haunted by unspeakable terrors. They had both become emaciated. She could feel her own ribs, and the bones in her back ached from leaning against the damp timbers.

She shifted slightly as she contemplated his request, aware of the wetness and filth washing about her feet. They were sitting where the planks of the floor sloped upwards to meet the curved wall of the ship’s hull. She could not imagine what it must be like for the hundreds of other prisoners crowded onto the lower level, lying in the slopping stench of their own waste.

…in that fleeting daylight she had seen how he looked older than his twelve years, his eyes haunted by unspeakable terrors.

“I don’t think I can sing, Fisher,” she said.

“Please.”

She remembered singing to him in another life, within the soft furs of their long, family bed. All six of her younger siblings had loved her singing to them on stormy nights, when rain hissed on the thatch just above their heads, and the youngest ones wished their parents slept under the rafters with them, instead of in the curtained alcove downstairs. They all depended on Elowen, since she was the eldest. She kept them calm, and sang away their childish fears and frightening dreams. She could not bear to think of their distress now the family was torn apart. Her own grief was too much to bear, and she kept it locked behind a vast numbness that was part shock, part disbelief at what had happened. Sometimes, on the edge of exhausted sleep, she still imagined that she would wake and find it all an appalling dream.

“Elowen?” Her brother’s voice was quavering and feeble, like an old man’s.

“Very well,” she said.

For several minutes she struggled to think of a song. But the place of songs was gone, vanished beyond grief and endless, paralysing fear. She could not remember tunes or words, or summon the energy to sing, or think of a reason to sing. Except that she must, for Fisher’s sake. Four years younger than Elowen, he was a child still.

I must be strong for him, she thought. I need to be strong for him, else he won’t survive.

For several minutes she struggled to think of a song. But the place of songs was gone, vanished beyond grief and endless, paralysing fear.

With an enormous effort she stilled the chaos of her emotions, and found her reason to sing: one tiny spark of gratitude. She was not alone. There was still Fisher. He had not died, like the others. It was a great thing to be thankful for. And with the gratitude came an old Penhallow folksong, from the Isles where she was born.

Her voice faltered at first, rasping and faint from thirst, but then the song and its words lifted her, flew her above the place where she was, made her forget; and her voice grew strong, sweet and clear and beautiful.

After a while, she realised that somehow, something in the darkness had changed. It was silent. The incessant groaning, the pitiful crying, had ceased. They were all listening.

Her voice wavered, faded.

“Sing on, sweetheart, whoever you are,” said a voice from the blackness.

“You give us courage.”

So she sang another song, amazed to find strength where she thought there was none. To her surprise, a voice joined her … then another, and another, until the fetid dark echoed with the sounds of hope. She wept while she sang, overwhelmed with humbleness and awe. At home, the villagers had said they loved to hear her sing, but now, for the first time, she realised the power of her gift.

From the deck above came the tramp of heavy boots and the thud of a mallet on a wooden drum, marking out a rhythm for the galley slaves to row by. Gradually the other voices in the hold died away, but Elowen sang on, not songs but wordless melodies that matched the drum’s tempo, and rose and fell and wove in the gloom like a thread of gold. Her listeners lay utterly silent, transported for a time above their distress.

Gradually the other voices in the hold died away, but Elowen sang on, not songs but wordless melodies that matched the drum’s tempo, and rose and fell and wove in the gloom like a thread of gold.

Almost imperceptibly, a grey glow began to appear above their heads, through the black grid of the iron grating. The grey evolved into pink, then a dazzling blue. The drum beat on, relentless and urgent, and the captives knew that in the world above there was no wind. The triangular red and yellow sails would have been pulled down, and the galley slaves, the most cruelly used of all captives, were toiling under a punishing sun.

Then the heat rose in the hold and Elowen stopped singing, every breath now a struggle to survive. The stinking air became suffocating, her tongue stuck to the roof of her mouth, and she could feel her heart labouring within her ribs. Sweat ran down her face and neck, and trickled between her breasts. She was naked, as were all the captives, the humiliation and shame part of their captors’ power.

Sleeping now, Fisher sagged against her. Elowen could hear the timbers of the ship creaking, feel the movement as the sleek hull surged through the waters of an unknown sea. She had lost count of the days they had been here in the stifling hold of the pirate galleon, though some reckoned it had been six weeks. They must be half a world away from her home on the coast of the southernmost island of the Penhallows; a world away from life as she had known it. Separated from all that was familiar, she knew only that they had been seized by slave-trading pirates and were being transported to slave markets on the coast of far-off Rabakesh. What horrors lay ahead, she could not bear to imagine.

They must be half a world away from her home on the coast of the southernmost island of the Penhallows; a world away from life as she had known it.

Suddenly the grating above was hauled aside, and out of the blinding light she saw the shape of a bucket lowered on a rope. Shielding her eyes, she saw a dark man with long braided hair leaning through the gap, a basket in his hand, then pieces of bread rained down, like manna from a terrible heaven. The semi-dark became a sea of seething bodies fighting for the single water-bucket and the meagre lumps of fallen bread. Women sobbed, pleading for bread for their children, while others called pitifully up to their captor, begging in vain for mercy.

Feeble hands grasped for the bucket of water, people slurping desperately for only a moment or two before it was grabbed away. Some drank too long, and were beaten by their neighbours, gentle souls turned vicious in their agony of thirst. When the bucket reached Elowen it was almost empty. She tipped it until the murky liquid only wet her parched lips, then passed it on to Fisher. He took one mouthful, then whimpered as the bucket was snatched away by someone else.

Leaning against the hull, Elowen ate her bread slowly, her stomach heaving, the mouldy chunk like dirt in her mouth. Above her, the pirate drew up the empty bucket. A few moments later a man not far from Elowen struggled to his feet. He carried a dead woman in his arms.

People did their best to get out of his way as he stumbled to the wooden steps leading to the grating and deck. He staggered up into the brightness, past the pirate, and was gone a few moments. He came back alone, slumped over in pain and sorrow, and limped down the steps and over to his place in the dark.

The pirate barked down an order no one understood, before slamming the grating shut. For a while, the only sound was the sobbing of the bereaved man.

Elowen bent her head in her arms, lost in her own grief for the ones she loved who, weeks ago, had been carried away up those steps and slipped into the watery grave.

Extracted with permission from The King’s Nightingale by Sherryl Jordan, published by Scholastic NZ.