By Gordon and Sarah Ell

There has been an enormous amount of amazing local non-fiction in recent months – and here’s a taster of one of those releases. Volcanoes and Earthquakes by Sarah and Gordon Ell is part of Oratia’s ‘The NZ Series’ and this extract is reproduced with permission.

Volcanic Eruptions

By bringing molten rocks to the surface, volcanoes can deposit useful minerals on the surface of the earth. The molten rock (magma) may cool in various forms such as andesite or basalt. Inside these rocks there may be crystals or precious metals. Their composition is determined by the kinds of rock beneath the earth, and the effects on them of heat.

Magma flowing from the mouth of a volcano is known as lava. Sometimes it flows quite swiftly, forming a surface skin, while molten rock, at 1000°C or more, rushes underneath like an underground river. At other times it moves slowly, twisting and breaking as it cools, into piles of broken rock and scoria. There may be ‘bombs’ of rock thrown from the volcano as molten lumps, reshaped as they cool, falling to earth like giant stone teardrops.

Sometimes [lava] flows quite swiftly, forming a surface skin, while molten rock, at 1000°C or more, rushes underneath like an underground river.

Rock formations caused by flowing rivers of basalt are sometimes called pahoehoe, and produce billowing shapes, pillows of lava as may be seen in the cliffs at Oamaru and at Muriwai, west of Auckland. The broken surface of the rock produced by an aa (pronounced ‘ah-ah’) type eruption can be seen on Rangitoto Island and the scoria fields about the Auckland volcanoes, and at Mt Tongariro.

Tephra is a name used by geologists to describe material ejected as particles by a volcano (rather than lava, which flows as a mass of molten rock). Volcanic ash is a form of tephra, not the remains of something that has been burned like wood ash, for there is little burning in the volcano. The ‘smoke’ and ‘fire’ we may see during a volcanic eruption are actually gases escaping from the molten rock. Much of that gas is steam, and most ‘smoke’ coming out of a volcano is ash-charged steam.

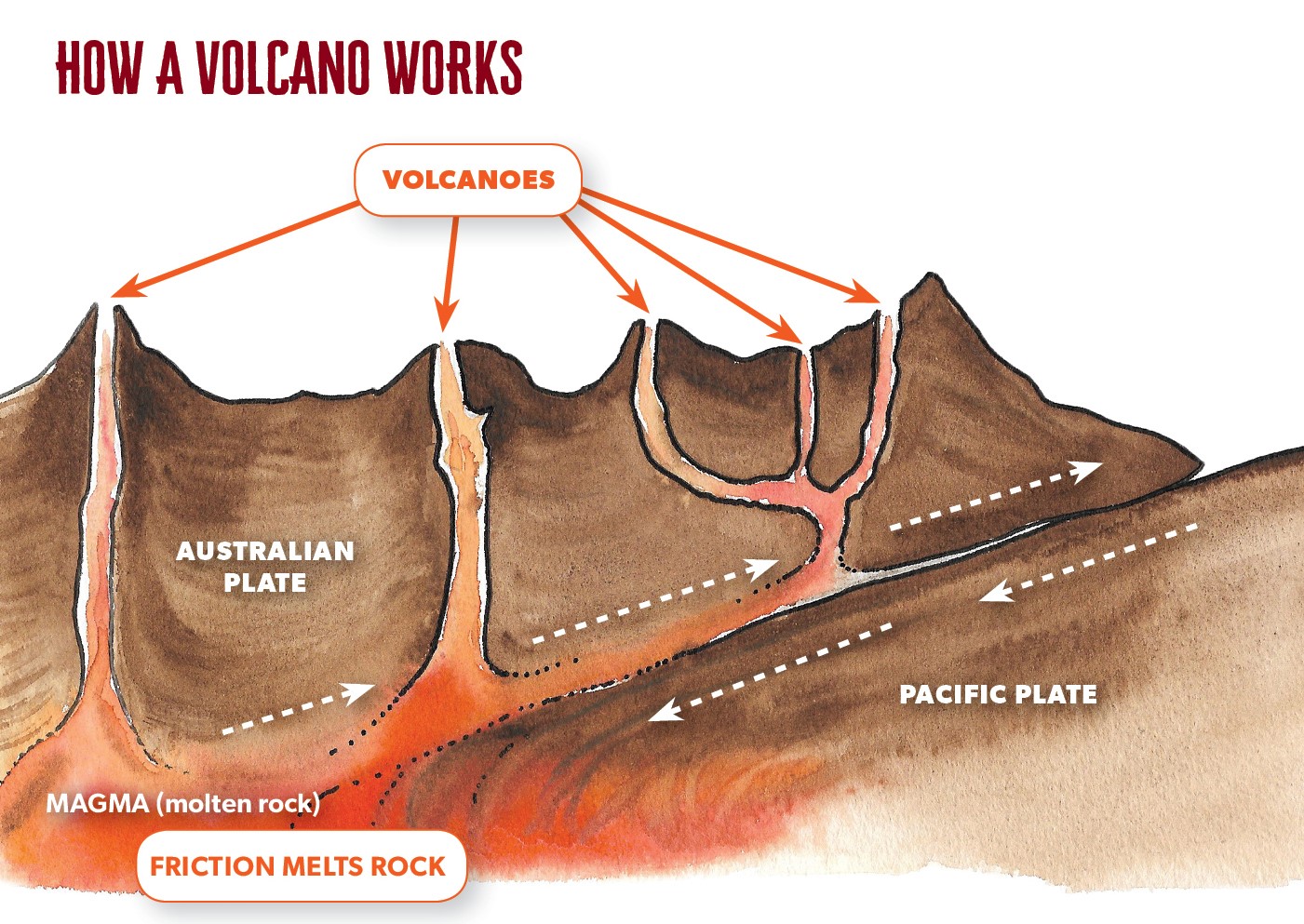

Under New Zealand, the Australian and Pacific plates grind against each other, causing earthquakes and allowing molten rock to reach the surface and escape as volcanoes. (image: Tim Galloway)

These gases, erupting with the molten rock, may roar up into the sky in vast clouds. Volcanic ash and pumice then coat the land surrounding the volcano. Pumice is a rock light enough to float on water: gas has filled it with holes which help it float. Pumice from the central North Island is often found on west coast beaches, washed down to the sea by the Waikato River.

Volcanic eruptions may vary in violence with the amount of gas built up in the molten rock. Where the rock is free-flowing the volcano may erupt quite gently, the basalt lava streaming away from the crater, as the gases escape easily into the atmosphere. This is how the little volcanoes of the Auckland isthmus were born.

Where the rock is thick and tacky, in its molten form, then it is difficult for the gases to escape. The result may be a catastrophic explosion. In such a way, great clouds of gas lifted the heart out of Lake Taupo in a huge eruption recorded as a darkening of the skies by the ancient Greeks and Romans, on the other side of the earth. Molten rock is carried high into the air, often expanding with the gases, to form great showers of pumice which then falls on the land.

[…Great] clouds of gas lifted the heart out of Lake Taupo in a huge eruption recorded as a darkening of the skies by the ancient Greeks and Romans, on the other side of the earth.

In another kind of eruption, gas may escape across the surface of the land carrying with it a wall of hot sand, molten glass fragments and pumice. The rush of material flattens any forest and settles as a mantle across the land. In such a way the central North Island has been built up into the Volcanic Plateau. Successive pumice showers overlay thick beds of ignimbrite rocks created by these gaseous eruptions.

Much of the central North Island, north from Taupo and Tarawera, is covered in tephra from volcanic explosions. It may be seen in layers from successive eruptions, in places like road cuttings and riverbanks. The roots and branches of trees, overcome by the eruptions, are often still to be seen in the layers.

It may be seen in layers from successive eruptions, in places like road cuttings and riverbanks.

Geologists have given names to the various ash showers, the layers of mud and pumice which cover the land. Like a layer cake, they show the extent and violence of various eruptions. The Tarawera eruption of 1886 scattered pumice over some 900 square kilometres, while the Taupo eruption some 1800 years ago covered some 6000 square kilometres.

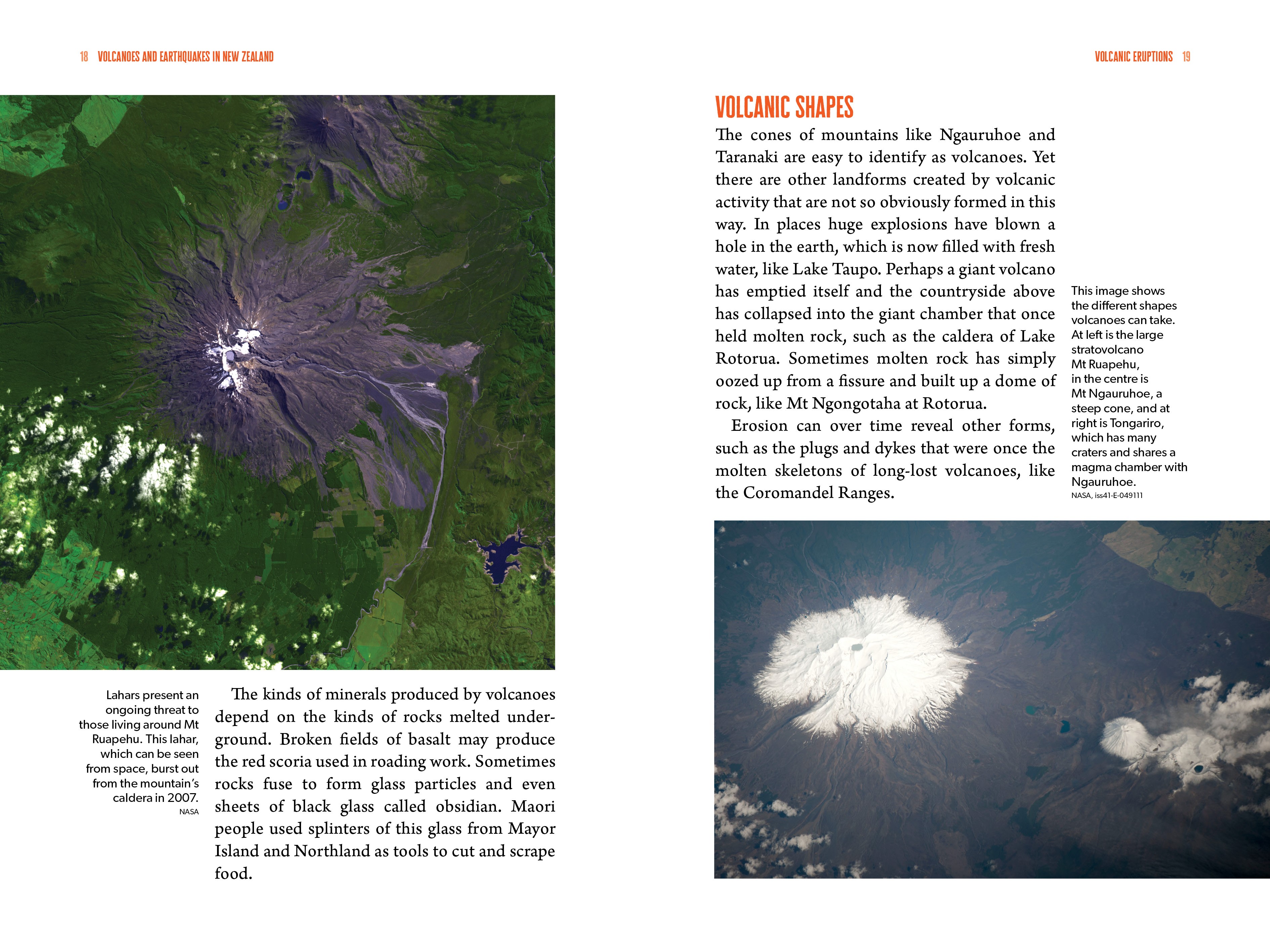

The weather and existing rivers may re-sort the deposits of ash. A river, held back by a new fall of ash, may form a temporary pond. When the dam of soft material bursts then the rush of water may coat the countryside in volcanic mud. Such mud flows are called lahars, and may leave hillocks on the land, as can be seen approaching the Chateau Tongariro Hotel and about Mt Taranaki. A mud flow bursting from the crater lake of Ruapehu in 1953 swept down the Tangiwai River, washing out a railway bridge and causing the deaths of 151 people when an overnight express train plunged into the river.

The kinds of minerals produced by volcanoes depend on the kinds of rocks melted under-ground. Broken fields of basalt may produce the red scoria used in roading work. Sometimes rocks fuse to form glass particles and even sheets of black glass called obsidian. Maori people used splinters of this glass from Mayor Island and Northland as tools to cut and scrape food.

Volcanic Shapes

The cones of mountains like Ngauruhoe and Taranaki are easy to identify as volcanoes. Yet there are other landforms created by volcanic activity that are not so obviously formed in this way. In places huge explosions have blown a hole in the earth, which is now filled with fresh water, like Lake Taupo. Perhaps a giant volcano has emptied itself and the countryside above has collapsed into the giant chamber that once held molten rock, such as the caldera of Lake Rotorua. Sometimes molten rock has simply oozed up from a fissure and built up a dome of rock, like Mt Ngongotaha at Rotorua.

The cones of mountains like Ngauruhoe and Taranaki are easy to identify as volcanoes. Yet there are other landforms created by volcanic activity that are not so obviously formed in this way.

Erosion can over time reveal other forms, such as the plugs and dykes that were once the molten skeletons of long-lost volcanoes, like the Coromandel Ranges.

Cone volcanoes, such as Ngauruhoe and Taranaki, are built up over centuries from steep layers of lava and ash. Such cones may produce secondary outlets as their main ‘throat’ becomes blocked with cooling magma.

Shield volcanoes are formed by runny magna, which flows quickly to form a smooth mound. Such volcanoes are quite easy to find in northern New Zealand. Often they are quite small, less than 100 metres high, such as the little Bay of Islands and Auckland cones. Their form is quickly produced, perhaps within two or three years, as basalt-type volcanoes rapidly exhaust their magma.

Extracted with permission from The NZ Series: Volcanoes and Earthquakes by Gordon Ell and Sarah Ell, published by Oratia Books.