By Dr Jo Prendergast

This year’s Mental Health Awareness Week runs from 18-24 September. This week, our content is focused on mental health, and we’re kicking off with an extract from psychiatrist and comedian Dr Jo Prendergast’s new book, When Life Sucks: Parenting teens through tough times. Covering everything from anxiety, depression, neurodivergence and gender identity, this guide is designed to help navigate rangatahi through the turbulent time that is teenagerhood. Check out an excerpt below.

In 1969, my parents announced ‘It’s a girl’ via telegram and handwritten letters. Growing up in the 1970s in New Zealand, I enjoyed what were regarded as typical ‘girly’ activities involving pink tutus and ponies and also some ‘tomboy’ pursuits in tree forts with stick guns and mud. My sex education consisted of awkwardly watching an educational video with my parents at school, a few passing conversations about ‘the birds and the bees’ at home and furtive reading of biology textbooks in the local library. My school crushes were all boys, usually with dark hair and long eyelashes (I kept a list of them in my diary). What I knew about ‘gender’ was boys grew up to be men who liked rugby, and girls grew up to be women who knew how to operate the washing machine. In our family there was a mix of traditional gender roles and more progressive values. My mother did most of the cooking and cleaning, but she was also one of only a few women in her university science class. In the 1980s, I met a few people whose gender was unclear, but asking about someone’s gender didn’t seem OK back then; nor was being gay generally accepted. Young people (and adults) would tease each other for being a ‘homo’ and New Zealand TV personalities ‘Hudson and Hall’ were described as ‘very good friends’.

I moved to Sydney in 1993 and my eyes were opened to a whole new world. For a while I worked as a psychiatry registrar at St Vincent’s Hospital in Darlinghurst, where the majority of my work colleagues were gay men. Over time I shifted from seeing them as my ‘gay friends’ to just being my friends.

What I knew about ‘gender’ was boys grew up to be men who liked rugby, and girls grew up to be women who knew how to operate the washing machine

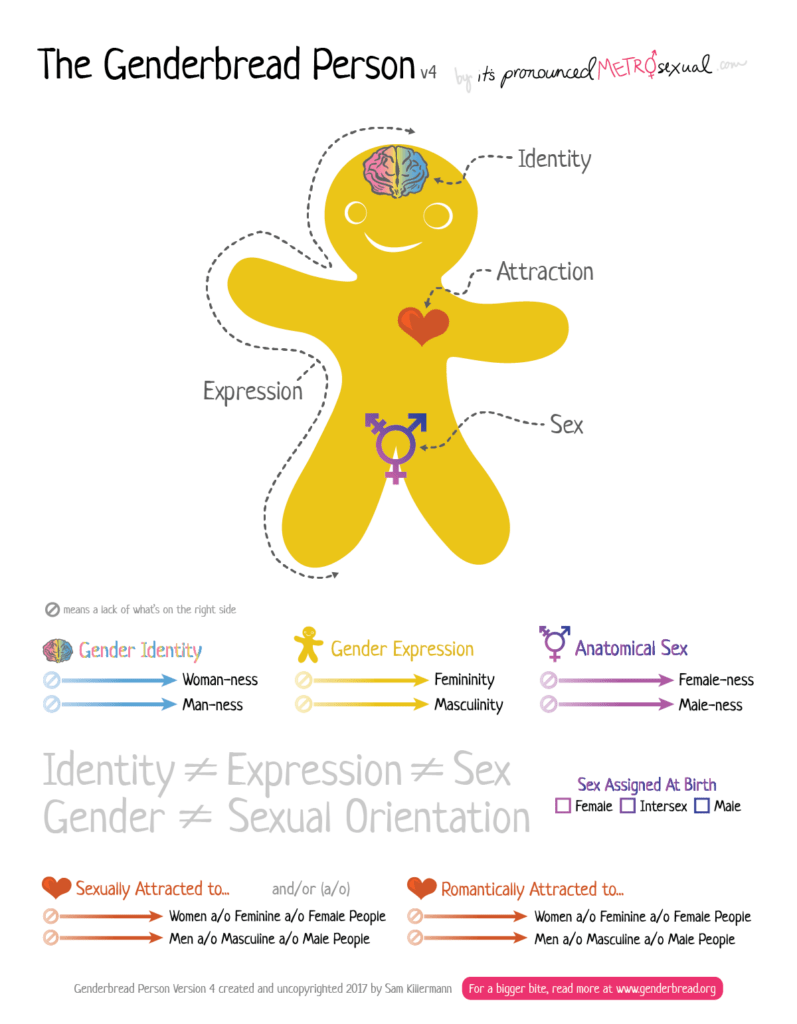

When I started in private psychiatry practice in New Zealand in 2013, one of the psychiatrists who had an interest in transgender mental health was retiring and asked if I was interested in accepting referrals. It was a huge learning curve, and like many others, I struggled at first with getting the terms right. For example, that ‘sex’ is what is assigned at birth, mainly based on what genitals you are born with (male, female or intersex); ‘gender identity’ is whether you feel like a woman, man or another gender; ‘gender expression’ is how you look and behave; ‘sexual orientation’ is who you are attracted to; LGBTQIA+ usually stands for lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, queer, intersex, asexual + others.

Different people and countries use different terms. In New Zealand the term ‘Rainbow’ is used by many official organisations. Some young people refer to themselves as queer. The general rule is to ask an individual person which terms they want you to use. I found the ‘Genderbread person’ image a useful way to understand the terms.

Social acceptance plays a very important role in the mental health of those who are transgender

In my practice, I started to regularly see young adults who were transgender for mental health ‘clearance’ before they started hormone treatment. I’m sure I learnt much more from them than they learnt from me. There were many common themes in their stories, particularly the high level of distress they experienced at puberty, and the huge relief and improvement in their mental health when they came out as transgender and started the process of gender-affirming hormones. My experiences hearing these stories and working overseas in the 1990s made me aware that many cultures around the world have recognised and accepted genders beyond the binary (women and men) for some time. Social acceptance plays a very important role in the mental health of those who are transgender. This is backed by research that has found that kids who are supported to live as the gender with which they identify, and have family acceptance, have fewer mental health difficulties.

Many of my colleagues on the comedy circuit are members of the Rainbow community (LGBTQIA+) including some who are gender diverse. I’m sure my psychiatry and comedy work experience has helped my personal understanding and acceptance. People who haven’t had this experience sometimes find differences in gender identity and sexual orientation difficult to understand, particularly when they have grown up in an era or environment where these differences weren’t understood or accepted.

In recent years, several friends and family members have supported their teens with hormone treatment to affirm their gender identities and this has increased my understanding of what it’s like to be a parent going through this situation. What’s clear is that teens who are trans/gender diverse have improved mental health when their gender identity is supported and others use their preferred name and pronouns (for example, he, she, they). This is also the strong recommendation from the New Zealand Ministry of Health and the New Zealand and Australian College of Psychiatrists RANZCP. If you take one thing from this, please use the name and pronouns a trans/gender diverse person wishes you to use!

What’s clear is that teens who are trans/gender diverse have improved mental health when their gender identity is supported and others use their preferred name and pronouns

Rejecting a person’s stated gender can have flow-on effects, causing severe distress and actual mental disorders. There is a clear message from NZ government and health organisations that a person’s gender identity is to be respected and that trans rights are human rights. My college of psychiatrists RANZCP’s official position is ‘all experiences of gender are equally healthy and valuable’.

Here’s a few recent New Zealand stats (from the latest Youth19 survey) relating to teen sexuality and gender identity. New Zealand teens are having sex for the first time later than they were, with 25 per cent of 16 year olds in 2019 compared to 37 per cent in 2012. The 2019 survey found that 16 per cent of 13–18 year olds did not identify as heterosexual; stating being attracted to same or multiple, not sure or not attracted to any sex.

The same survey found 1 per cent of teens identified as non-binary (gender identity that is neither a man or a woman) or transgender, and another 0.6 per cent were not sure of their gender (this is lower than the 2012 survey where 1.2 percent identified as transgender and 2.5 per cent weren’t sure of their gender). The majority of these teens (73 percent) started to identify as trans/gender diverse before the age of 14. So, many teens (but decreasing numbers) are having sex and quite a few teens identify as part of the LGBTQIA+ Rainbow community.

The most important thing we can do as parents is accept and walk alongside our teens

There are high rates of mental health and social difficulties for Rainbow teens, especially when there is a lack of family support. (Alarmingly, the 2019 NZ survey indicated around 60 per cent of transgender teens reported depression and 25 per cent had attempted suicide in the last year.) But there are also positives found in the survey; for example, Rainbow teens are more likely to give back to the community than other teens.

The most important thing we can do as parents is accept and walk alongside our teens. Even if they are ‘cis* and straight’ we can ask ourselves about what messages we are giving them about people who are different from us. How they treat their Rainbow school friends can make a big difference to those teens’ mental health.

*The origin of ‘cis’ is from chemistry, where trans = opposite side and cis = same side. ‘Cis’ translates to my sex (female) and the gender my parents announced in 1969 (girl) matching with my own gender identity (woman) and gender expression (wearing long hair, makeup and dresses). ‘Heterosexual’ is my sexual orientation/attraction, being a woman attracted to men. It can be hard for people who are ‘cis’ to really have any idea what it would be like if our gender identity didn’t match our sex assigned at birth. Hopefully this extract helps parents have more understanding of this topic.

When Life Sucks: Parenting your teen through tough times

By Dr Jo Prendergast

Published by HarperCollins Publishers New Zealand

RRP: $37.99